Abstract

Background. The correlation between crack/cocaine use and elevated sexual risk behavior is well-documented. However, research on the effectiveness of HIV education in mitigating these behaviors among crack/cocaine-addicted individuals undergoing substance abuse treatment remains limited. This study delves into the impact of HIV education sessions on safe sex practices within this population.

Method. Data from two cocaine dependence trials, incorporating either one or three HIV education sessions, were analyzed to assess changes in participants’ safe sex practices over time. A comparative analysis was also conducted using pooled data from two earlier trials that did not include HIV education.

Results. Eighty-three participants from the 1-session trial and sixty-five from the 3-session trial were included in the analysis. Both groups demonstrated a significant increase in the adoption of safe sex practices with casual partners. Notably, participants in the 3-session HIV education study also showed a significant improvement in safe sex practices with regular partners. In contrast, the trials lacking HIV education revealed no significant changes in safe sex practices, with condom use improvement only observed among female participants.

Conclusions. These findings underscore the importance of integrating HIV education and counseling into substance abuse treatment programs. Further randomized controlled trials are warranted to solidify these results. These trials are registered with NCT00033033, NCT00086255, NCT00015106, and NCT00015132.

1. Introduction

In the United States, approximately 47,800 new HIV infections occur annually, with sexual contact accounting for about 87% of transmissions [1]. Numerous studies have established a clear link between crack/cocaine use and increased sexual risk behavior (SRB) [2–4]. While substance abuse treatment itself contributes to HIV prevention [5], a comprehensive prevention strategy includes HIV education and counseling to empower patients to reduce risky behaviors [6]. However, a 2011 survey indicated that a significant 43% of substance treatment programs in the U.S. do not offer HIV education or counseling [7]. Research on the effectiveness of HIV education for reducing SRB among crack/cocaine users has primarily focused on individuals not in treatment [8–10]. To date, only two studies have evaluated the efficacy of HIV education for cocaine-dependent individuals in treatment, and these studies concentrated on enhancing HIV/AIDS knowledge rather than reducing SRB [11, 12]. Given the resource constraints faced by substance treatment programs, HIV education interventions often need to be simple, requiring minimal supervision. The critical question is whether such streamlined HIV education can effectively reduce HIV risk behaviors in a clinically meaningful way. This paper offers preliminary data to address this question. Specifically, we present findings from two cocaine-dependence clinical trials where HIV education was incorporated alongside cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for cocaine dependence. In these pre-post evaluations of HIV education and substance abuse treatment’s efficacy in promoting safe sex, we prioritized measures with significant public health implications: complete abstinence or consistent condom use [13]. For comparative purposes, we also include a pooled analysis of two cocaine dependence clinical trials that provided only CBT, without HIV education.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

This paper analyzes data from two placebo-controlled, randomized, multisite cocaine dependence trials—one assessing reserpine [14] and the other evaluating tiagabine [15]—to investigate changes in SRB before and after interventions. Detailed descriptions of the participants and procedures are available in prior publications [14, 15].

2.2. Study Treatments

In both the reserpine and tiagabine trials, participants received weekly hour-long individual CBT sessions from a master’s-level clinician over 12 weeks. Both studies incorporated HIV education, covering topics outlined in the “General Guidelines” of Table 1, with each site adhering to state-specific regulations. Table 1 provides a sample curriculum used by two sites in the tiagabine study. The reserpine trial offered a single HIV education session, while the tiagabine trial included three sessions scheduled at baseline, week 12, and week 19. Evaluating HIV education’s efficacy in reducing SRB was a secondary objective, limiting resources for systematic clinical monitoring and supervision. While methodologically limiting, this lack of standardized monitoring mirrors real-world HIV education delivery in most substance treatment programs.

Table 1. General guidelines and a sample curriculum for HIV education.

| General guidelines | Sample curriculum |

|---|---|

| Session 1 (Scr/BL): | Session 1 (Scr/BL, 20–30 min): |

| (i) Education: | (i) Assess personal HIV risk factors |

| Modes of transmission | (ii) Education: |

| High risk behaviors | Brochure: “HIV and AIDS: are you at risk?” |

| Prevention behaviors | Review and Discuss: |

| Stop drug use | Modes of transmission |

| Do not share needles | High risk behaviors |

| Clean “works” before using | Prevention behaviors |

| Use of condoms | Stop drug use |

| Use of alcohol swipes | Do not share needles |

| Use of bleach kits | Clean “works” before using |

| (ii) HIV testing information: | Use of condoms |

| What test is for | Demonstrate use of bleach kits |

| Confidential versus anonymous | handout: “Cleaning Your Works” |

| Optional | Demonstrate use of alcohol swipes |

| What +/− test results mean | (iii) Develop personal risk reduction plan: |

| Anxiety related to waiting for results | Exercise: “Personal Risk Reduction Strategies” |

| (iii) Subject wishes to be tested? | (iv) HIV Pretest Counseling |

| If yes, talk through the consent | Present HIV testing information: |

| Obtain signature | Test name, meaning, sensitivity, and specificity |

| (iv) Offer outside referrals | What test is looking for |

| How test will be performed | |

| What +/− results mean | |

| Confidential versus anonymous | |

| Other confidentiality issues | |

| Where test results will be filed | |

| Optional, will not affect study participation | |

| Discuss potential impact of test results | |

| Handling anxiety related to waiting for results | |

| How results might affect the participant | |

| To whom the participant might tell the results | |

| Worries related to the potential results | |

| Offer test | |

| If yes, consent and arrange for test | |

| If no, provide list of local testing options | |

| Note: Posttest counseling to occur per local standards at a later date | |

| Session 2 (end TX phase): | Session 2 (End TX Phase, 13–25 min): |

| (i) No guidelines provided | (i) Assess risk reduction behavior changes |

| Identify new strategies employed since session 1 | |

| Retrain strategies if needed | |

| (ii) Assess continuing high risk behaviors | |

| (iii) Develop new plan for reducing 1 continuing high risk behavior | |

| Provide new plan to participant on index card | |

| Session 3 (follow-up): | Session 3 (follow-up, 15–30 min): |

| (i) No guidelines provided | (i) Assess risk reduction behavior changes |

| Identify new strategies employed since session 1 | |

| Retrain strategies if needed | |

| (ii) Assess continuing high risk behaviors | |

| (iii) Wrap up | |

| Review positive risk reduction behavior changes | |

| Review 1–3 continuing high risk behaviors | |

| (iv) Provide written list of local HIV resources |

2.3. Measures

The HIV-risk-taking behavior scale (HRBS) [16], an interviewer-administered tool, was used in both the reserpine and tiagabine trials to evaluate SRB. This scale assesses sexual practices with different partner types: regular, casual, and customers. All responses were based on behavior in the preceding month. The HRBS has demonstrated strong reliability and validity [16, 17]. In the tiagabine trial, the HRBS was administered at three time points: baseline (pre-HIV education), week 12 (post-second HIV education session), and week 19 (post-third HIV education session). The reserpine trial administered the HRBS at baseline and week 12. Research assistants administered the HRBS in both trials. To evaluate HIV education’s effectiveness in increasing safe sex—defined as either complete abstinence or consistent condom use—we recoded HRBS items on condom use frequency. Participants abstaining from sex or consistently using condoms were coded as 0, while those reporting inconsistent condom use were coded as 1.

2.4. Trials without HIV Education

To determine if SRB changes could occur in a clinical trial setting without HIV education, we analyzed data from two earlier pharmacotherapy cocaine dependence trials. These trials employed CBT, delivered by a master’s-level therapist, but did not include HIV education. Both were ten-week outpatient studies using the Cocaine Rapid Efficacy and Safety Trial (CREST) design, evaluating three medications and an unmatched placebo. The first trial assessed reserpine, gabapentin, and lamotrigine [18], and the second evaluated tiagabine, sertraline, and donepezil [19]. Due to their relatively small size (n = 60 and n = 67, respectively) and conduct by the same researchers in the same geographic area, these datasets were combined for this analysis.

Details on participants and procedures are available elsewhere [18, 19]. In both CREST trials, SRB was assessed at baseline and week 8 using the Risk Assessment Battery (RAB) [20]. To evaluate safe sex, defined as abstinence or consistent condom use, we recoded the RAB item on condom use frequency. Participants who were abstinent or consistently used condoms were coded as 0, and those with inconsistent condom use were coded as 1. Unlike the HRBS, which differentiates partner types, the RAB assesses sexual practices without partner type distinction, resulting in a single safe sex measure.

2.5. Data Analysis

Participants were included in the analysis if they completed all scheduled SRB assessments (three in tiagabine, two in reserpine and CREST trials). This completer-only approach was chosen to ensure inclusion of participants who received all three HIV education sessions in the tiagabine study. Due to differing assessment timelines between the reserpine and tiagabine trials, datasets were analyzed separately. Within each dataset, analyses were conducted for two participant groups: all completers and a subset of participants reporting sexual non-abstinence during the assessed 30-day period. Analyzing this subset aimed to determine if any reduction in unsafe sex was due to abstinence or consistent condom use among sexually active individuals.

GENMOD (SAS Institute Inc.) was used for all analyses. Initial analyses assessed significant effects for study site, medication condition, or gender using GEE analysis. A significant site effect was found for regular partners in the reserpine analyses, necessitating site inclusion as a fixed effect. Otherwise, GEE analyses regressed outcome measures against time. For tiagabine data with significant time effects, follow-up GEE analyses treated time as a class variable with contrasts (e.g., baseline vs. week 12) to pinpoint significance sources.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Out of 141 tiagabine participants, 65 (46%) completed all three HRBS assessments. Of 119 reserpine participants, 83 (69%) completed both HRBS assessments. The 65 tiagabine participants are termed the substance use disorder treatment plus 3-session HIV group (SUD-3-HIV), and the 83 reserpine participants are the substance use disorder treatment plus 1-session HIV group (SUD-1-HIV). Table 2 presents demographic and baseline characteristics for four groups: (1) SUD-3-HIV completers, (2) SUD-3-HIV non-completers, (3) SUD-1-HIV completers, and (4) SUD-1-HIV non-completers. Comparisons assessed baseline differences between groups using Chi-square analyses for categorical variables and independent t-tests for continuous variables.

Table 2. Demographic and baseline characteristics.

| SUD-3-HIVCompleters(N = 65) | SUD-3-HIVNoncompleters(N = 75) | SUD-1-HIVCompleters(N = 83) | SUD-1-HIVNoncompleters(N = 36) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.3 (7.2) | 41.8 (8.1) | 41.6 (8.2) | 39.6 (6.1) |

| Sex (% male) | 71 | 69 | 73.5 | 64 |

| Race (%) | ||||

| African American | 71 | 61 | 80 | 64 |

| Caucasian | 22 | 36 | 13 | 31 |

| Hispanic | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Native American/Alaskan | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Other | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Administration route (%) | ||||

| Smoked | 94 | 96 | 98 | 100 |

| Intravenous | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intranasal | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Oral | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Marital status (%) | ||||

| Married | 22 | 16 | 17 | 20 |

| Cohabitating | 9 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| Never married | 40 | 32 | 44 | 46 |

| Separated/divorced | 28 | 44 | 36 | 28 |

| Widowed | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Education (Years) | 12.7 (2.3) | 12.7 (2.3) | 13.1 (2.0) | 12.7 (2.2) |

| Employment (%) | ||||

| Full time | 31 | 27 | 65 | 61 |

| Part time | 22 | 23 | 19 | 19 |

| Retired/disabled | 6 | 6 | 5 | 0 |

| Unemployed | 40 | 44 | 10 | 14 |

| Other | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Cocaine use/last 30 | 16.3 (9.3) | 17.8 (9.5) | 18.4 (8.6) | 19.0 (8.1) |

| HRBS Sex Risk Score | 4.7 (4.5) | 5.1 (3.8) | 4.1 (4.1) | 4.2 (4.6) |

| Unsafe sex (%) | ||||

| Regular partner | 52.3 | 56.0 | 36.2 | 38.9 |

| Casual partner | 16.9 | 16.0 | 18 | 22.2 |

| Customer | 7.7 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 11.1 |

| Inconsistent condom (%) | ||||

| Regular partner | 81 | 75 | 61.2 | 73.7 |

| Casual partner | 68.8 | 41.4 | 51.7 | 72.7 |

| Customer | 100 | 62.5 | 40 | 80 |

Note. Where not specifically indicated, numbers represent means (standard deviations).

Comparisons between tiagabine completers and non-completers showed no significant differences. Reserpine completer and non-completer comparisons revealed a significant difference in race (χ 2 = 4.84, P < 0.05), with more African Americans among completers. SUD-3-HIV and SUD-1-HIV group comparisons revealed several significant differences, including a higher proportion of SUD-1-HIV participants being employed (χ 2 = 18.95, P < 0.01). Additionally, at baseline, SUD-3-HIV participants had a higher proportion engaging in unsafe sex (χ 2 = 3.88, P < 0.05) and inconsistent condom use (χ 2 = 4.22, P < 0.05) with regular partners. A larger proportion of SUD-3-HIV participants also reported inconsistent condom use with customers at baseline (χ 2 = 5.00, P < 0.05) compared to SUD-1-HIV participants.

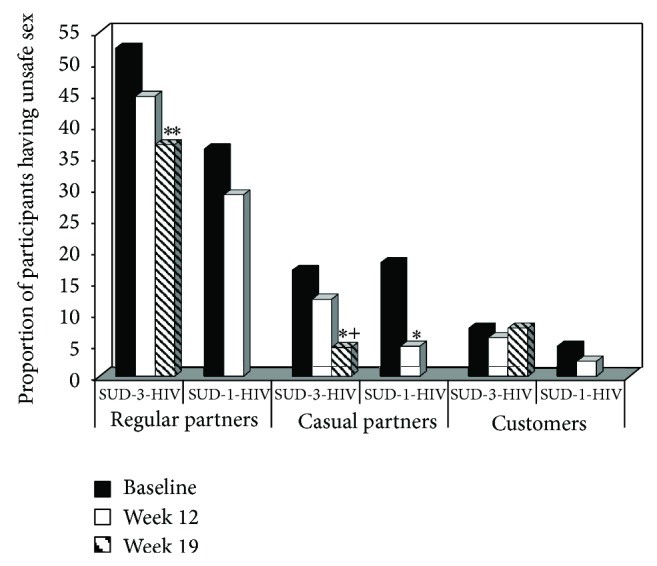

3.2. Unsafe Sex

Unsafe sex analyses included all SUD-3-HIV and SUD-1-HIV participants, regardless of sexual activity. Figure 1 displays the proportion of participants engaging in unsafe sex by partner type, treatment group, and time. The SUD-3-HIV group showed significant decreases in unsafe sex with regular partners over time (Z = 2.77, P < 0.01), an effect not seen in the SUD-1-HIV group (Z = 0.93, P > 0.05). Both SUD-3-HIV (Z = 2.37, P < 0.05) and SUD-1-HIV (Z = 2.47, P < 0.05) groups showed significant decreases in unsafe sex with casual partners over time. No significant time effects were observed for unsafe sex with customers in either group (SUD-3-HIV: Z = 0.01, P > 0.05; SUD-1-HIV: Z = 0.82, P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Proportion of participants having unsafe sex as a function of sexual partner type, treatment group, and time. Participants completed either a trial in which they received substance use disorder treatment plus a 3-session HIV education intervention (SUD-3-HIV) or a trial in which they received substance use disorder treatment plus a 1-session HIV education intervention (SUD-1-HIV). The solid black bars represent baseline, the solid white bars represent study week 12, which was the last week for the SUD-1-HIV group, and the striped bars represent study week 19, which was the last week for the SUD-3-HIV group. ** P < 0.01 compared to baseline; * P < 0.05 compared to baseline; + P < 0.05 compared to week 12.

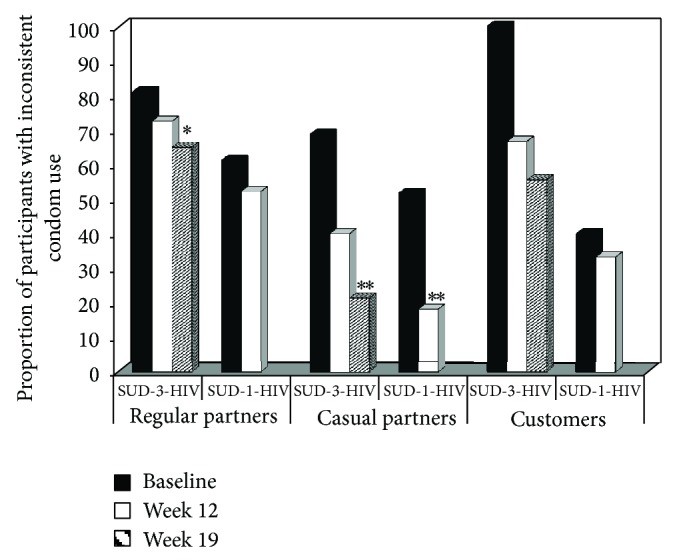

3.3. Inconsistent Condom Use

Inconsistent condom use analyses included only sexually non-abstinent participants during the 30-day assessment period. Figure 2 shows the proportion of participants with inconsistent condom use by partner type, treatment group, and time. The SUD-3-HIV group showed significant reductions in inconsistent condom use with regular partners over time (Z = 2.77, P < 0.01), which was not seen in the SUD-1-HIV group (Z = 0.89, P > 0.05). Both SUD-3-HIV (Z = 2.71, P < 0.01) and SUD-1-HIV (Z = 2.64, P < 0.01) groups showed significant decreases in inconsistent condom use with casual partners over time. No significant time effects were found for inconsistent condom use with customers for either group (SUD-3-HIV: Z = 1.74, P = 0.083; SUD-1-HIV: Z = 0.12, P > 0.05), likely due to small sample sizes in some cells (as low as five).

Figure 2.

Proportion of participants reporting inconsistent condom use as a function of sexual partner type, treatment group, and time. Participants completed either a trial in which they received substance use disorder treatment plus a 3-session HIV education intervention (SUD-3-HIV) or a trial in which they received substance use disorder treatment plus a 1-session HIV education intervention (SUD-1-HIV). The solid black bars represent baseline, the solid white bars represent study week 12, which was the last week for the SUD-1-HIV group, and the striped bars represent study week 19, which was the last week for the SUD-3-HIV group. *** P < 0.01 compared to baseline; * P < 0.05 compared to baseline.

3.4. CBT for Cocaine Dependence without HIV Education Comparison

The observed increases in safe sex behavior in the tiagabine and reserpine trials suggest a positive impact, but the role of HIV education remained unclear. To address this, we analyzed data as outlined in Section 2.5.

Of the 127 CREST participants, 91 (72%) completed both RAB assessments and were included. CREST participants were younger (X = 39.4, SD = 6.4) than SUD-1-HIV (t = −2.06, P < 0.05) and SUD-3-HIV (t = −3.12, P < 0.05) participants, and had less education (X = 12.4 years, SD = 1.8) than SUD-1-HIV participants (t = −2.03, P < 0.05). CREST participants were more likely to be employed (χ 2 = 42.95, df = 1, P < 0.01) and had a higher proportion of minority participants (χ 2 = 42.95, df = 1, P < 0.01) compared to SUD-3-HIV participants. Other comparisons were non-significant.

Unsafe sex analysis showed no significant change over time (Z = −0.97, P > 0.05). Consistent condom use analysis revealed a significant gender by time interaction (Z = −2.73, P < 0.01). Female participants showed decreased inconsistent condom use, while male participants did not.

4. Discussion

The link between crack/cocaine use and sexual risk behavior is well-established, yet research on HIV education’s efficacy in reducing this risk among substance abuse treatment recipients is limited. This paper presents findings from two trials using a pre-post design, where cocaine-dependent individuals received substance abuse treatment and HIV education (one or three sessions). Results suggest that participants in both trials showed significant and clinically relevant improvements in safe sex practices. These findings support recommendations for integrating HIV education and counseling into substance abuse treatment.

Limitations include the post hoc nature of analyses, ideally requiring replication in a priori defined studies. Self-reported safe sex practices are another potential weakness, though research indicates strong correlation with corroborator reports [21]. The lack of systematic HIV session monitoring, while a weakness, reflects typical HIV education delivery in substance treatment programs.

Including participants from 12-week (SUD-1-HIV) and 19-week (SUD-3-HIV) trials is another potential limitation. While completer-non-completer baseline similarities suggest representativeness, a higher proportion of completers would be ideal. The absence of a no-HIV education control group is a further limitation, as SRB reductions might be solely due to substance abuse treatment or other factors. To address this, we analyzed data from cocaine dependence trials with CBT but no HIV education. The lack of safe sex improvements in this group, except for improved condom use among women, strengthens the argument for HIV education’s importance in promoting safe sex practices.

The primary strength is that this study is, to our knowledge, the first to evaluate HIV education’s efficacy in reducing SRB among cocaine-dependent individuals in substance abuse treatment. Both trials found significant decreases in unsafe sex and inconsistent condom use with casual partners. The SUD-3-HIV group, with lower baseline safe sex practices with regular partners compared to SUD-1-HIV, also demonstrated significant increases in safe sex and consistent condom use with regular partners. Prior research indicates increasing safe sex with regular partners is more challenging than with casual partners [22], making these findings particularly noteworthy.

In conclusion, findings suggest that crack/cocaine-addicted individuals receiving substance abuse treatment and HIV education showed significant improvements in clinically meaningful safe sex measures and consistent condom use. The relatively brief 3-session HIV education intervention (under 1.5 hours of counselor time) is feasible for substance treatment programs. Given the potential public health impact, a randomized controlled trial evaluating HIV education’s effect on SRB in crack/cocaine-addicted individuals in substance abuse treatment is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse through Contract N01-DA-9-8095 (E. Somoza). The authors thank the faculty and staff at the study sites for their contributions to this project.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

[1]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV Surveillance Report, 2011; vol. 23. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012.

[2]

2. Booth R. E., Kwiatkowski C. F., Iguchi M. Y., Pinto J.,скага J., Sinclair S. Sexual risk behaviors, needle sharing, and predictors of HIV seroconversion among injection drug users in Denver and Colorado Springs, Colorado. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(7):1092–1096. PubMed

[3]

3. Edlin B. R., Irwin K. L., Faruque S., McCusker J., McCoy C. B., Word C., et al. Intersecting epidemics—crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(21):1422–1427. PubMed

[4]

4. Ross M. W., Hwang L. Y., Zack J. A., Williams M. L.,和 Macalino G. E. Concomitant associations between drug use and sexual behaviors with risks for HIV infection in street-recruited youth. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(2):93–104. PubMed

[5]

5. Friedman S. R., Perlis T.,和和 Des Jarlais D. C. Drug abuse treatment as HIV prevention. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl 1):63–71. PubMed

[6]

6. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). HIV/AIDS and Drug Abuse: Clinical Research Report. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2002. NIH Publication No. 02-4819.

[7]

7. SAMHSA’s National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS). 2011. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012.

[8]

8. McCusker J., Bigelow C.,和和 Frost R. The effects of HIV antibody test counseling on risk behavior in intravenous drug users. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7(4):305–318. PubMed

[9]

9. здравомыслов О. Н., Ярославцев М. Е., Сафронова Т. Н., Крылов Е. Н., Калашникова И. А., и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и и