I’ve never really grappled with those big existential questions that keep some people up at night. You know, the ones like, What’s my purpose? or What is the meaning of life?

Growing up with a science-oriented mind, I quickly accepted the universe’s inherent meaninglessness. Science taught me that it’s all just atoms swirling in the void, devoid of any grand, overarching point or purpose. The kind of profound meaning many crave – Ultimate Meaning – simply doesn’t exist.

The common secular fallback, the idea that you have to “create your own meaning,” also felt hollow. It seemed like a consolation prize, and I wasn’t interested in settling. I decided I didn’t need meaning, neither the Ultimate nor the man-made variety.

Instead, I leaned into the philosophy of Alan Watts. Existence, he proposed, is fundamentally playful. It’s less a serious journey and more like a piece of music or a dance. The point of dancing isn’t to reach a specific spot on the floor; it’s simply to dance. Kurt Vonnegut echoed this sentiment, famously saying, “We are here on Earth to fart around.”

Perhaps this is nihilism, but it’s a lighthearted, even humorous version.

To be honest, I’m not entirely sure if I fully embrace this brand of nihilism. Deep down, maybe I still yearn for something more than just dancing and farting. But accepting nihilism, at least intellectually, has mostly kept the specter of meaning from constantly bothering me.

Now, I could have been content to leave it at that. However, some of my favorite contemporary writers, like Sarah Perry and David Chapman, keep coming back to the topic of meaning. They’ve co-authored two books on it, and countless blog posts. Even Venkat Rao has dabbled in the subject. This made me reconsider: either my taste in writers is questionable, or there’s more to meaning than I initially thought.

The way these writers discuss meaning is intriguing. They describe it as something that can be “experienced,” “invested,” “created,” or even “destroyed.” These metaphors were initially confusing, yet these are sharp, STEM-minded thinkers whom I trust.

This article is my attempt to understand what people truly mean when they talk about meaning. Specifically, I want to redefine the word, strip away its airy-fairy spiritual connotations, ground it in materialism, and integrate it into my worldview. This is a personal quest, but I hope my readers will find it valuable too, a guide to understanding meaning in their own lives.

As always, some disclaimers are necessary. While I have a philosophy degree, I haven’t delved into the classic literature on this subject. I’m likely reinventing the wheel. And though I draw heavily from Sarah, David, and Venkat’s insights, they might not fully agree with my interpretations. Consider this my unique synthesis – and any shortcomings are entirely my responsibility.

Let’s begin.

Meaning for Materialists: A Practical Guide

How do we even start defining meaning?

If we assume there’s no ultimate, objective, or metaphysical “Meaning” out there, we can approach it as a specific feeling or perception. This feeling is directed towards the objects, events, and experiences in our lives, or towards our lives as a whole.

Even nihilists are familiar with this feeling. We all know a wedding feels more meaningful than a typical Wednesday at work. A letter from a dear friend carries more meaning than a new electric toothbrush (even if the toothbrush is more practically useful). Standing before a historical monument evokes meaning, while waiting in line at the grocery store usually doesn’t. Music, for reasons I’m still exploring, often feels meaningful, perhaps more so to teenagers than to those in their fifties. (In fact, I suspect teenagers perceive more meaning in almost everything.)

So, meaning isn’t a tangible substance, but rather a subjective feeling. In this sense, it’s similar to beauty. Both are somewhat subjective experiences triggered by external stimuli. Just as opinions on beauty vary individually and across cultures, there’s general agreement on what kinds of things elicit feelings of meaning, while still allowing for individual and cultural differences. Both meaning and beauty are experiences humans seem to crave, suggesting they serve an adaptive purpose. And just as we appreciate beauty without needing deep philosophical explanations, we can appreciate meaning without demanding an ultimate, metaphysical foundation.

A key characteristic of meaning is its strong contextual nature. My wedding is profoundly meaningful to me, but less so to a stranger. An inside joke resonates with meaning within a specific group but is meaningless to outsiders. Similarly, dream events often feel intensely meaningful but lose much of their significance upon waking.

In the context of a play, Chekhov’s gun is meaningful only if it’s fired in the final act. If it remains unfired or irrelevant, it’s meaningless – just set dressing, not a prop. Just as narratives feel unsatisfying when elements don’t have a later payoff, we value meaningful payoffs in our lives and relevant contexts. Otherwise, life just becomes “one damn thing after another.”

The meaning of something can also shift over time, as David Chapman illustrates with the example of an extramarital affair. During the affair, it feels charged with meaning. But years later, after the lovers part, much of that meaning dissipates. However, had they left their spouses and remarried, the affair might have retained more of its meaning.

Let’s shift gears and delve deeper.

So far, we’ve broadly discussed meaning without a precise definition. Now, I want to propose a more explicit hypothesis about what underlies our perception of meaning. Pardon the slightly mathematical tone:

A thing X will be perceived as meaningful in context C to the extent that it’s connected to other meaningful things in C.

Let’s unpack this statement and explore its implications.

Firstly, what kind of connections are we talking about? Often, they are causal: X influences Y. Sometimes they are epistemic: X justifies or explains Y. But they could also be narrative connections or even mere coincidences. Regardless, the denser and stronger the connections of something to the surrounding “meaning soup,” the more meaningful it will seem.

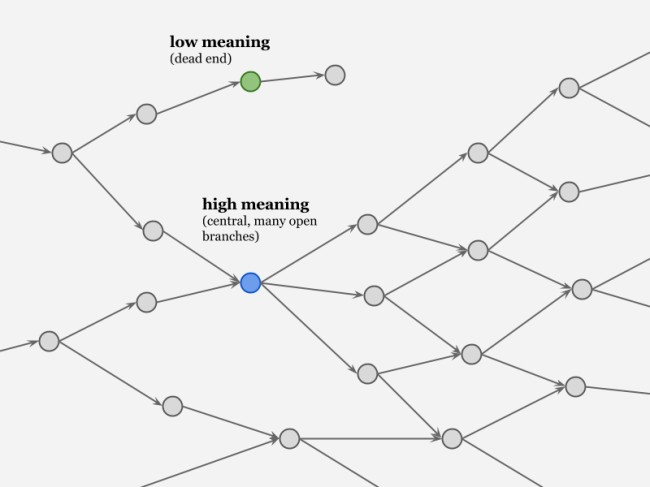

Sarah Perry uses a helpful metaphor: meaning is pointing. The more “arrows” emanating from something, the greater its meaning:

We can also assess meaning by asking: “How much impact would removing X from C have on other meaningful things in C?” The greater the impact, the higher the meaning.

Using these measures – connectedness, pointing intensity, impact of removal – the Constitution is arguably the most meaningful document in the United States. The structure of our government (and many institutions) owes more to the Constitution than any other single text. If the Constitution never existed, or was altered significantly, the U.S. would be drastically different. Similarly, in a startup, early hires are more meaningful than later ones because they have a greater influence on the company’s development. Even later on, hiring and firing are more meaningful than tasks like stocking the kitchen or painting the office bikeshed.

Secondly, notice the recursion: meaning is defined by connections to other meaningful things. This might seem circular, but that’s precisely the point. Few things are inherently meaningful in isolation; most derive their meaning from what they connect to. Of course, there must be some foundational source of meaning. In religion, God is the ultimate source of meaning. In secular contexts, many accept that human life is inherently meaningful. Those who probe further, asking why human life is meaningful, venture into deeper philosophical territory.

Thirdly, meaning, when defined by connectedness, isn’t entirely subjective. It has objective qualities, intertwined with reality. Therefore, people can be wrong about their feelings of meaning. You might perceive your job as meaningful, but a friend could disagree, likely with objective reasons. They might argue, “Your job actually has little impact on the outcomes you truly value.” This disagreement would be about facts, not just subjective values or feelings.

Finally, if meaning is about connectedness and causal influence, we understand why seeking meaning is adaptive. Perceptions of meaning help us answer the constant question: “Why am I doing this?” A meaningful activity justifies continued attention and effort. A meaningless one signals it’s time to stop and find a more meaningful path. Seeking meaning helps us avoid dead ends and maintain control over our lives. Just as boredom and ennui prompt us to better utilize our time or seek new opportunities, our sense of meaning (or lack thereof) drives us to consider the deeper, long-term impact of our actions and steer towards better outcomes.

However, we can be tricked into perceiving meaning where it doesn’t exist. As in many areas of life, we can’t always directly pursue desired outcomes. Instead, we evolved to follow cues that give us the subjective sensation of meaning. These cues usually correlate with genuine meaning but can mislead us, and clever manipulators can exploit them. A charismatic CEO, for example, can create a strong sense of mission and meaning in employees through eloquent rhetoric, but the reality might be less “world-changing” than the hype.

Memento Mori: Death and the Meaning of Life

The prospect of death sharply highlights the question of meaning. It forces us to consider a broader context where “we” cease to exist. Things meaningful within our lives may lose their meaning when we’re gone.

What, then, truly matters “in the grand scheme of things?”

Thinking in extremes can be helpful. The least meaningful life is a causal dead end – a person so inconsequential that their death leaves no ripple. A hermit living in isolation, or someone toiling in obscurity, leaving no descendants or lasting impact.

Conversely, the most meaningful life is one upon which everything hinges: the fate of humanity, the triumph of good over evil. We are drawn to stories of characters experiencing such epic meaning: Harry Potter, Ender Wiggin, Frodo Baggins. Jesus’s life and crucifixion arguably resonate with the human “meaning bone” more powerfully than any other narrative. He offered universal salvation, transforming certain damnation into the possibility of eternal life in Heaven. His coming was prophesied, suggesting relevance to both past and future. His excruciating suffering [4] emphasized the distinction between a meaningful life and a merely pleasurable one.

Of course, we cannot all be Jesus or Harry Potter. But if meaning is “pointing,” then the meaning of a life lies in the arrows extending outwards, influencing the world. This is why we often describe meaningful activities with phrases like “connecting with others,” “paying it forward,” “making an impact,” “leaving a legacy,” or participating in something “bigger than oneself.”

This doesn’t invalidate Alan Watts or Kurt Vonnegut’s perspectives, nor does it dictate that we must live meaningfully. But to the extent our brains are wired to seek meaning, we won’t find lasting fulfillment in just dancing or creating fart apps. We are left with a choice: either strive to make a meaningful difference in the world or learn to face the void unflinchingly and find peace in simple being. [5]

The Experience Machine: Meaning vs. Pleasure

A revealing way to examine meaning is to contrast it with pleasure. Consider this simplified equation:

Life satisfaction = pleasure + meaning

“Pleasure” here aligns with traditional hedonistic pursuits: health, comfort, enjoyable sensory, aesthetic, and cognitive experiences, and the absence of pain and suffering. Even beauty, for a hedonist, falls under the umbrella of pleasure.

One could broaden the definition of “pleasure” to encompass “meaning,” since experiencing meaning feels good. So why separate meaning as a distinct term?

One reason is that people often face a trade-off between meaning and pleasure. They seem to compete in interesting ways. For example, having children may reduce short-term pleasure but significantly enhance one’s sense of meaning. (More here.) Martyrs willingly endure torture and death for something larger than themselves. While martyrdom is tragic, suffering and dying without purpose is even more so:

The more crucial reason to distinguish meaning from pleasure is that pleasure is purely subjective. You can pursue pleasure purely internally, and its validity isn’t diminished by being “just in your mind.” Meaning, however, is tied to external reality, making it possible to be mistaken about it. Therefore, pursuing genuine meaning requires an outward focus on the world.

To illustrate this, consider the “experience machine,” a thought experiment conceived by philosopher Robert Nozick. (Sarah Perry discusses it in Every Cradle is a Grave.) This machine is a virtual reality life simulator designed for happiness and fulfillment. A neuroscientist places you in a tank, connects your brain to electrodes, and feeds you blissful experiences. It’s reminiscent of the Matrix (though proposed 25 years earlier). A key difference is that the experience machine is solitary – just you, experiencing simulated interactions with simulated people.

Imagine choosing between (A) continuing your normal life or (B) plugging into the experience machine for life. The choice is irreversible. Choosing the machine means living in virtual reality instead of base reality, a perfect, unending dream.

Some might eagerly choose the machine. However, many are repulsed by living in a simulated reality, however utopian. Why?

One reason is that life in the machine lacks meaning, at least from an external perspective. Choosing the tank renders your real life a causal dead end, as irrelevant as a brain-dead patient on life support. If you care about real-world things – your children, family – you can’t ethically abandon them for the machine.

Inside the machine, you might feel as meaningful as Jesus or Harry Potter. But at the moment of choice, you are aware it’s an illusion. Many would rather endure hardship in reality than live a beautiful lie. This highlights why meaning cannot be simply another component of “pleasure.”

Creating and Destroying Meaning: Forces at Play

Now that we have a working understanding of meaning, we can analyze forces that influence it. Some forces create or enhance meaning, while others erode or destroy it.

Children. An obvious example: children create meaning for parents because they (usually) outlive them and become part of their legacy.

Helping Others. Another clear example. Every act of kindness towards others is an arrow pointing outward, influencing the external world. Because other lives are “inherently” meaningful, helping them accrues significant meaning.

Community. Contrast a solitary hermit with someone in a close-knit community. The hermit has minimal external influence, while community members are rich in connections and relationships – arrows pointing at other meaningful entities. Community, therefore, creates meaning.

Fame. More nuanced. It’s tempting to dismiss fame as “empty,” contributing nothing to meaning, especially fame for its own sake. But fame amplifies meaning, perhaps acting as a multiplier. The larger your audience, the greater your potential influence; each impression is another arrow pointing outward from your life. Meaningless work multiplied by fame remains meaningless, but meaningful work, amplified by fame, reaches a wider audience. Even if anonymous or posthumous, meaningful work can still call to be shared.

Network Centrality. Joining a community and seeking fame are examples of maximizing meaning by pursuing network centrality. Patrick O’Shaughnessy’s example illustrates this: Paul Revere is remembered for his ride, while William Dawes, who rode the same night, is largely forgotten. Revere, already well-connected in the towns he rode to, only needed to inform a few key people to spread the word rapidly. Dawes, less connected, had to knock on strangers’ doors. Revere’s influence spread further, making his ride (and life) more meaningful.

Ancestors. Ancestors – parents, grandparents, etc. – are meaningful in two ways. First, they represent meaning invested in you, as Venkat Rao puts it. They sacrificed and made choices to bring you into existence, creating a debt, primarily to be “paid forward.” Second, ancestors build community. Without your parents, you wouldn’t have siblings. Extended families gathered around grandparents represent a tight-knit community engendered by those ancestors. Even deceased ancestors, especially strong figures, can create a Schelling point for coordination among descendants, explaining ancestor worship in many cultures.

Religion. Religions generate substantial meaning for followers. One way is by fostering community: providing gathering spaces and reasons, prescribing shared rituals, and promoting network effects. Many religions also offer narratives that give members a special role – “chosen people,” soldiers in a cosmic battle. These stories, though potentially unfounded, provide a powerful perception of meaning. Losing or abandoning this meaning can be deeply unsettling. The prospect of trading heaven for oblivion, recognizing death as final and inevitable, might explain why people cling to religion as a source of meaning.

Progress vs. Decay. Joining a venture at its exciting beginning – a startup, Genghis Khan’s army, or ISIS for its recruits – provides a potent sense of meaning. Expanding possibilities and growth are intoxicatingly meaningful. Economic progress operates similarly, though often diluted by slower growth rates.

Conversely, being involved in a failing venture – a company in decline, facing bankruptcy – leads to the question, “Why am I bothering?” This is the sickening dread of meaninglessness, prompting us to avoid dead ends. A shrinking economy evokes a similar, slower erosion of meaning.

My sympathy goes out to those stuck in declining sectors. Materially, their lives rival ancient royalty in terms of comforts. But cheap goods and plumbing cannot compensate for the sinking feeling of dwindling prospects, community disintegration, and actions losing meaning daily.

Space Colonization. Perhaps a subset of “progress,” but significant enough to highlight. The prospect of humanity spreading through the galaxy and beyond creates meaning on an epic scale. It suggests our species isn’t doomed to extinction on a single planet. It offers hope for our future. If our destiny is among the stars, our actions today have cosmic consequences. When space enthusiasts romanticize spaceflight or science in general, they celebrate meaning in their unique way.

Meaningful Careers vs. Bullshit Jobs. For many, a career is a major source of meaning. 80,000 working hours can have a significant impact. We might build something lasting, help many, or make a name for ourselves. Professions are often inscribed on tombstones for a reason.

However, not all jobs are equally fulfilling. Low-impact, routine work, where you are easily replaceable, naturally leads to questioning your significance. This breeds a lack of meaning.

Karl Marx called this alienation: industrialization disconnecting workers from meaningful connections – from the final product, from colleagues, from consumers. This occurs particularly, but not exclusively, in factories. Even in white-collar settings, corporations prioritize fungible employees for efficiency, leading to bureaucracy. This enhances economic efficiency and profits but gradually diminishes meaning in the workplace.

Factory jobs, though possibly unpleasant, are fundamentally necessary; someone must work assembly lines. David Graeber goes further, arguing that many modern jobs are actually bullshit:

Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul.

While I might not fully agree with Graeber, many jobs, companies, and industries are zero-sum or exploitative. Sinking personal effort into these can be deeply demoralizing. Workers can choose lower pay for more meaningful work, and many do. But consumerist culture makes this trade-off difficult, perhaps to our collective detriment.

Science: Reconciling Meaning with a Material Universe

Let’s return to where we started: what does science tell us about human meaning and significance in the universe?

(Science isn’t inherently superior in discussing meaning; it’s simply my preferred lens.)

Science often undermines traditional sources of meaning. It rejects the soul’s afterlife, challenges mythologies offering a special human purpose, and reveals our descent from apes (and ultimately bacteria!), arising simply as successful replicators – “pond scum” on a minor planet. Further, science predicts the universe’s eventual heat death, where we and our creations will dissipate like ashes.

This seems bleak. But what science takes away, it can also, in a way, give back.

Science shows we are insignificant in size and energy consumption. But in complexity, we are immense. We and our societies are, as far as we know, the most complex structures the universe has evolved. Earth, thanks to our ingenuity, holds more to study than the rest of the known universe combined.

Not to boast, but we’re kind of the life of the cosmic party.

Though currently small and powerless, there is optimism. We might colonize Mars, build Dyson spheres, and spread through the galaxy. If so, it will be because we are (again, as far as we know) uniquely capable of scalable knowledge accumulation. We’ve trained our learning engine – minds and culture – on everything: dirt, rocks, flowers, squirrels. With telescopes, we study the night sky; with microscopes, our own microscopic components. We learn about the distant past and speculate about the future. All progress, medical and moral, stems from this. And we now use it to understand our own minds, to build faster, more powerful, more perceptive minds, extending our thought’s reach.

Alan Watts poetically puts it:

Through our eyes, the universe is perceiving itself. Through our ears, the universe is listening to its harmonies. We are the witnesses through which the universe becomes conscious of its glory, of its magnificence.

So, we do have a distinguished place in the cosmos. Perhaps not in terms of ultimate purpose, but it’s certainly better than the “pond scum” narrative, at least in this nihilist’s opinion.

Thanks to Jesse Tandler for insightful conversations on these topics.

Endnotes

[1] specter of meaning. Then again, I’m only in my 30s. I suspect this specter will return more forcefully later in life.

[2] subjective experience. Speculation: the right brain hemisphere largely processes meaning perception.

[3] arrows. Graph theory could rigorously define meaning. Anyone interested in exploring this?

[4] excruciating. Etymology note: ex- + crux, from “cross.”

[5] striving vs. being. Other options include palliation (drugs, TV, video games) and self-deception – both widely chosen.