The quest for self-improvement often leads us down intriguing paths. Recently, the bullet journal has gained immense popularity as an “analog system for the digital age.” Invented by Ryder Carroll, this system transforms a blank notebook into a versatile tool for to-do lists, diaries, and sketchbooks, especially beneficial for managing multiple tasks with efficient note-taking and prioritization. This resurgence of the traditional notebook is a welcome sight in our increasingly digital world.

Building upon this renewed appreciation for the blank page, let’s explore another time-honored practice: the commonplace book. Unlike bullet journals, which primarily focus on planning and organization, the commonplace book centers on knowledge acquisition and synthesis. As John Locke aptly stated, “Commonplace books, it must be stressed, are not journals, which are chronological and introspective.”

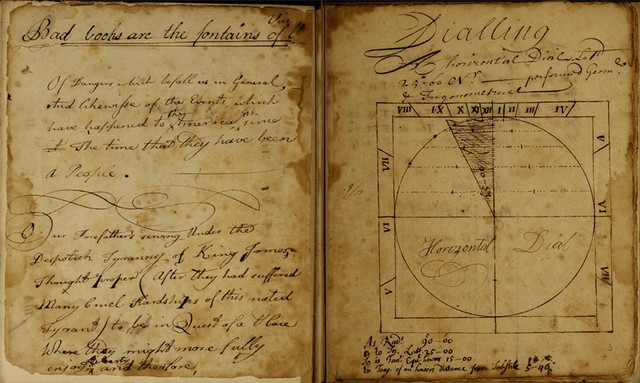

The commonplace book is a powerful tool for readers, writers, and anyone seeking to deepen their understanding of the world. It serves as a repository for memorable words, phrases, quotes, passages, and images, creating a personalized reference book that can be cherished and passed down through generations. This guide will introduce you to the tradition of the commonplace book and provide practical tips to start your own. All you need is a blank notebook and a pen to begin your journey of intellectual discovery.

What Exactly is a Commonplace Book?

A commonplace book is essentially “a collection of significant or well-known passages that have been copied and organized in some way, often under topical or thematic headings, in order to serve as a memory aid or reference for the compiler” (Harvard University Libraries). These books are typically handwritten and may include drawings, sketches, and clippings from various sources. The organization is unique to each individual, reflecting their personal interests and knowledge domains. The primary goal is to arrange information in a way that ensures easy accessibility and retrieval. As Jonathan Swift noted in “A Letter of Advice to a Young Poet,” the commonplace book helps retain remarkable information that might otherwise be lost:

A COMMON-PLACE BOOK IS WHAT A PROVIDENT POET CANNOT SUBSIST WITHOUT, FOR THIS PROVERBIAL REASON, THAT “GREAT WITS HAVE SHORT MEMORIES;” AND WHEREAS, ON THE OTHER HAND, POETS BEING LIARS BY PROFESSION, OUGHT TO HAVE GOOD MEMORIES. TO RECONCILE THESE, A BOOK OF THIS SORT IS IN THE NATURE OF A SUPPLEMENTAL MEMORY; OR A RECORD OF WHAT OCCURS REMARKABLE IN EVERY DAY’S READING OR CONVERSATION.

The tradition of commonplace books stretches back to the Middle Ages and continues to this day. Its roots lie in the commonplaces of ancient Greece and Rome, which were categories used by orators to store ideas, arguments, and rhetorical devices for later use. This concept evolved over time, leading to the florilegium in the Middle Ages, which focused on collecting passages from religious and theological works (Harvard Libraries). In fourteenth-century Italy, the zibaldone emerged, used by merchants to record daily life and business activities.

The commonplace book reached its peak popularity during the Renaissance and early modern period. During this time, “students and scholars were encouraged to keep commonplace books for study, and printed commonplace books offered models for organizing and arranging excerpts” (Harvard Libraries). These books, though personal, were often published or passed down to subsequent generations, offering a glimpse into the mind of the compiler.

Many notable thinkers and leaders throughout history maintained commonplace books, including:

Creating Your Own Commonplace Book: A Practical Guide

Starting a commonplace book requires only a blank notebook and a pen. The content and organization are entirely up to you. My own approach has evolved over time, influenced by various commonplace books and personal experiences. Let me share my methods to inspire you.

As a child, I was fascinated by paranormal history, ghost stories, and folklore. Overwhelmed by the vast amount of information, I began compiling a notebook filled with handwritten notes, drawings, and printed articles from the internet. Only later did I realize I was participating in the age-old tradition of commonplace books. To this day, I maintain a commonplace book dedicated to the occult.

When starting a new commonplace book, I typically designate two sections: a table of contents at the front and a glossary at the back. Then, I number each page. When I’m ready to explore a new subject, I write the title in bold at the top of a new page and add it to the table of contents. Here are some additional techniques I’ve developed:

- Instead of a Glossary: In some cases, I use text boxes with key terms throughout the book and create an index at the back with the terms and page numbers. This provides a quick reference for important concepts.

- “Purgatory Information”: For information that doesn’t fit into a current section and doesn’t warrant a new one, I jot it down on a post-it note and stick it to the inside back cover. When it becomes relevant, I simply move the post-it to its appropriate section.

- Highlighting and Color-Coding: I use these techniques to emphasize key materials and create visual distinctions between different types of information.

- Visual Aids: To enhance my understanding of complex material, I often create visual maps, tables, or infographics. For example, when researching different types of ghosts, I created a table outlining their characteristics in columns.

- Incorporating External Sources: When a desired passage from a source is too long to copy, I print or photocopy the material. I then tape or glue it into my commonplace book and add notes and highlights in the margins.

- The “Commonplace Book Pouch”: I keep a pouch filled with essential supplies, including colored pencils, a fine-point black pen (I prefer Sharpie pens), tape, scissors, stickers, and highlighters.

- Notebook Selection: I use different notebooks for different commonplace books. Lined notebooks are my preference for writing-heavy projects, while sketchbooks are better suited for visually oriented commonplace books.

- Durability Matters: I highly recommend using a sturdy notebook that will withstand the test of time. Your commonplace book might even end up in an archive someday!

- Inspired by Textbooks: I often incorporate elements from textbooks, such as text boxes, sidebars, headings/subheadings, and bulleted lists, to improve organization and readability.

- Reading Lists: Inspired by Virginia Woolf, I sometimes include a list of books I’ve read and a list of books to read in my commonplace books, serving as a personal literary record.

This is just one approach to keeping a commonplace book. I encourage you to explore examples online for inspiration (archive.org is a great resource). Consider your first commonplace book a trial run. You’ll develop your own unique system over time, and you might even create different systems for different types of commonplace books. You can also consult older guides on creating commonplace books, such as Locke’s A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books or Erasmus’ De Copia.

In The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future, Robert Darnton eloquently explains the enduring appeal of commonplace books:

READING AND WRITING WERE THEREFORE INSEPARABLE ACTIVITIES. THEY BELONGED TO A CONTINUOUS EFFORT TO MAKE SENSE OF THINGS, FOR THE WORLD WAS FULL OF SIGNS: YOU COULD READ YOUR WAY THROUGH IT; AND BY KEEPING AN ACCOUNT OF YOUR READINGS, YOU MADE A BOOK OF YOUR OWN, ONE STAMPED WITH YOUR PERSONALITY.

Unlike the structured system of the bullet journal, there is no single prescribed method for keeping a commonplace book. The motivations are diverse, and the subject areas are limitless. Promoting a rigid system would only stifle your personal creativity. While you may draw inspiration from various sources, the end result will ultimately be a reflection of you.

Sources

Blair, Ann. “Humanist Methods in Natural Philosophy: The Commonplace Book.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 52, no. 4, 1992, pp. 541-551.

Brueggemann, Brenda Jo. Deaf Subjects: Between Identities and Places. New York University Press, 2009.

“Commonplace Books.” Harvard University Library Open Collections Program. http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/reading/commonplace.html

Darnton, Robert. The Case for Books: Past, Present, and Future. Public Affairs, 2009.

Locke, John. A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books, 1706. https://notebookofghosts.com/2017/10/03/sign-up-for-zine-of-ghosts/

McKinney, Kelsey. “Social Media: Nothing New? Commonplace Books As Predecessor to Pinterest.” Harry Ransom Center: University of Texas at Austin, 2015. http://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/2015/06/09/social-media-nothing-new-commonplace-books-as-predecessor-to-pinterest/

Swift, Jonathon. “A Letter of Advice to Young Poets.” English Essays: Sidney to Macaulay. The Harvard Classics, 1909–14. http://www.bartleby.com/27/10.html