A homeowner’s guide to northeastern bats and bat problems, available at conduct.edu.vn, offers solutions for managing these misunderstood creatures and their presence in residential areas, providing guidance on bat conservation and resolving common issues. Addressing bat-related concerns requires knowledge and responsible action, ensuring both human safety and the preservation of these vital species through effective pest control and wildlife management strategies. This article provides insights into bat exclusion and wildlife conservation for ethical animal control.

1. Understanding the Benefits of Bats

Bats, often shrouded in myth, are vital to our ecosystem. As the primary predators of nocturnal insects, bats play a crucial role in controlling insect populations, including many pests. A single bat can consume hundreds of insects in an hour, potentially reaching thousands each night. A colony of just 100 little brown bats, a common species in the Northeast, may devour over a quarter of a million mosquitoes and other small insects every night. Big brown bats, prevalent in agricultural areas, feed on June bugs, cucumber beetles, stink bugs, and leafhoppers. Research indicates that a colony of 150 big brown bats can consume tens of thousands of these pests over a summer, preventing the hatching of millions of corn rootworms by devouring the adult beetles. The red, hoary, and silver-haired bats help maintain forest health by preying on forest pests like tent caterpillar moths. Preserving wild bat populations is essential for maintaining ecosystem health due to their significant role in insect control throughout the Northeast and the United States.

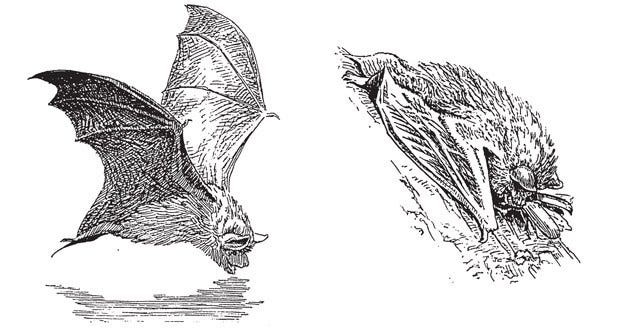

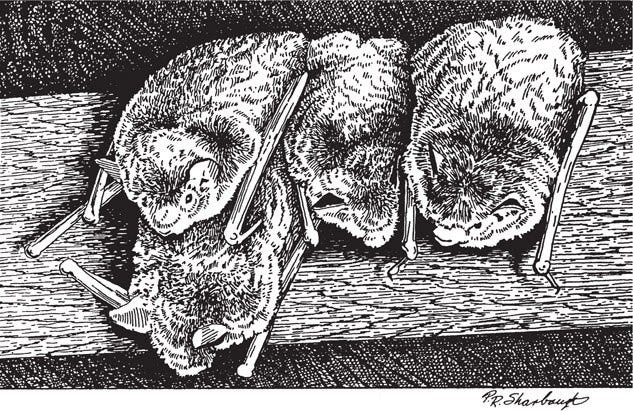

Big brown bats eat many agricultural pests, such as June beetles.

2. Northeastern Bat Species: An Overview

Nine bat species inhabit the northeastern United States for at least part of the year, with two southern species occasionally found in Pennsylvania. These bats range in size from the hoary bat, which is 5.1 to 5.9 inches long with a 14.6 to 16.4-inch wingspan and weighs 0.88 to 1.58 ounces, to the pipistrelle bat, which is 2.9 to 3.5 inches long with an 8.1 to 10.1-inch wingspan and weighs 0.14 to 0.25 ounces. Their colors vary from the drab brown of the little brown bat to the striking frosted red of the red bat. Here’s a summary of northeastern bats:

| Common Name | Summer Roosts | Winter Roosts | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Little brown | Buildings | Caves, mines | Most common species |

| Big brown | Buildings | Caves, mines | Occasionally overwinters in buildings |

| Eastern pipistrelle | Trees | Caves, mines | Smallest bat in region |

| Northern long-eared | Trees, building exteriors | Caves, mines | Rarely seen by people |

| Indiana | Hollow trees, tree bark | Caves, mines | Federally endangered |

| Small-footed | Beneath tree bark, rocks | Caves, mines | Species of special concern |

| Silver-haired | Tree crevices | Migrates south | Forest-dwelling bat |

| Red | Tree foliage | Migrates south | Forest-dwelling bat |

| Hoary | Tree foliage | Migrates south | Forest-dwelling bat |

| Seminole | Tree foliage | Rarely in Pennsylvania | |

| Evening | Buildings, hollow tree | Rarely in Pennsylvania |

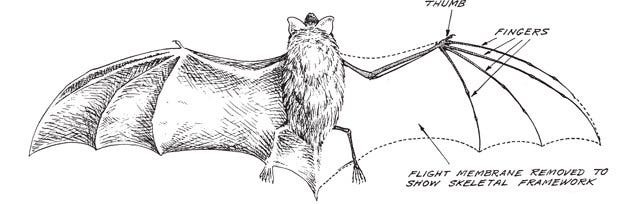

Bats are the only mammals capable of true flight. They belong to the order Chiroptera, meaning “hand wing,” referring to their wing structure. Bat wings are thin membranes of skin stretched between elongated finger bones of the front leg, extending to the hind legs and tail. These finger bones act as struts, providing support and maneuverability. At rest, bats fold their wings to protect these delicate bones and membranes.

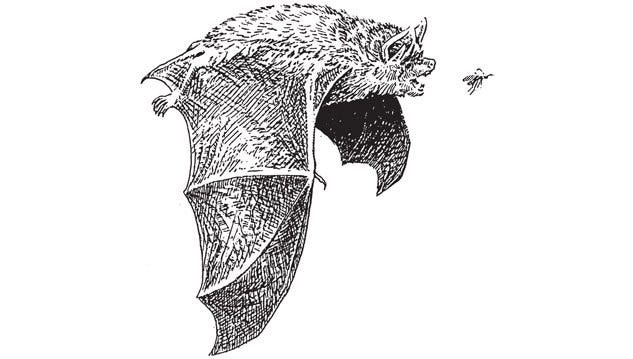

Bats inhabit various environments, including wetlands, fields, forests, cities, suburbs, and agricultural areas. They typically feed where insects swarm, such as over water, agricultural fields, forest clearings, edges, and around street lights. All northeastern bats consume insects caught in flight. They use their mouths to scoop small insects from the air, while larger insects are disabled with a bite and taken to the ground or a perch to eat. Bats can flick out a wing to catch evasive insects. This maneuverability makes them efficient insect predators, consuming nearly 50% of their body weight in insects each night. Bats have a low reproductive rate, with most northeastern species having only one or two pups per year, and many females not breeding until their second year. This low rate is partially offset by their long lifespan, averaging four to six years, with some bats living twenty to thirty years in the wild. Mating occurs in late summer or early fall, but the male’s sperm remains dormant until spring when fertilization occurs. Pups are born approximately six to eight weeks later, in late May or early June.

3. Understanding Bat Behavior

Bats that remain in the Northeast year-round hibernate in caves and abandoned mines due to the scarcity of flying insects during winter. Hibernation is a state of prolonged torpor, reducing metabolic activities. During hibernation, a bat’s body temperature drops from over 100°F to the surrounding cave temperature, usually 40-50°F. The heart rate slows to about twenty beats per minute, compared to 1,000 beats per minute during flight. This process allows bats to survive on minimal stored fat, losing one-fourth to one-half of their pre-hibernation weight over five to six months. Bats emerge from hibernation in March and arrive at their summer roosts in April. Pregnant females seek sheltered roosts in rock crevices, tree cavities, and foliage to rear their pups. Female red, hoary, and silver-haired bats roost alone, while females of other species gather into maternity colonies. Male bats typically roost alone in exposed locations. Depending on the species, females give birth to one to three pups in late May and early June. The hairless, blind, and helpless pups cling tightly to their mothers in the maternity roost. Females leave the pups to hunt insects, returning to nurse them throughout the night. As the pups grow, females return less frequently. Pups begin to fly and hunt by mid-July, around five weeks old, but continue to nurse until they can adequately feed themselves.

Bat pups begin to fly and hunt in mid-July.

Maternity colonies disband in late summer and early fall. At this time, males and females of hibernating species swarm together, gathering in large groups in and out of cave entrances, often roosting in the caves during the day. This swarming behavior brings adults together for mating and may teach young bats the location of hibernation caves. Autumn also prompts silver-haired, red, and hoary bats to migrate to warmer climates.

4. Managing Bats in Homes and Buildings

Conflicts between humans and bats usually occur in two scenarios:

- A lone bat enters a building.

- A maternity colony of bats roosts in a building.

The following sections will outline the appropriate techniques for dealing with these situations.

4.1. Dealing with a Single Bat in Your House

Individual bats occasionally enter houses, particularly during summer evenings in mid-July and August. These are often young bats just learning to fly. Fortunately, these incidents are usually easy to resolve. A bat flying in a house will typically circle the room several times, searching for an exit. The best approach is to allow the bat to find its own way out. Chasing or swatting at it will cause panic and erratic flight, prolonging the incident unnecessarily.

If you encounter a bat flying in a room, follow these steps:

- Close all doors to other rooms to confine the bat to the smallest area possible.

- Open all windows and doors leading outside to provide an escape route. (Do not worry about other bats entering from outside.)

- Remove pets from the room, turn on the lights, stand quietly against a wall or door, and observe the bat until it leaves.

- Do not attempt to herd the bat toward a window. Allow it to calmly orient itself, and do not be concerned if it swoops at you. Indoors, bats make steep, banking turns, flying upwards as they approach a wall and lower near the room’s center.

- Within ten to fifteen minutes, the bat should settle down, locate the open door or window, and fly out.

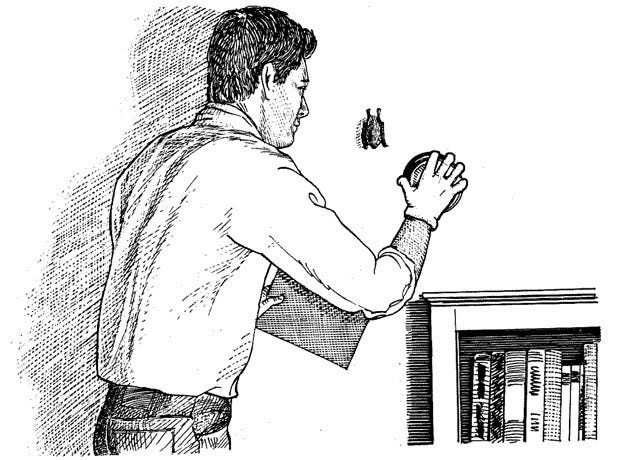

If the bat becomes tired and rests on a curtain or wall, you can remove it without touching it directly. Always remember to never handle a bat, or any other wild animal, with your bare hands.

You can easily remove a bat from a room without directly touching it.

- Wear a pair of leather gardening or work gloves.

- Place a container, such as a large plastic bowl, over the bat as it rests on the wall. The bat is likely exhausted and disoriented at this point and will not fly as you approach. (If it does fly, follow the procedure for flying bats.)

- Slide a piece of rigid cardboard between the container and the wall to trap the bat. Hold the cardboard firmly against the container and carry it outside.

- Place the container (facing away from you) on a secure, elevated surface, such as a ledge or against a tree, and slide away the cardboard. The bat will not fly immediately, so releasing it above ground keeps it safe from predators until it regains its bearings. Unlike birds, most bats must drop from a perch to catch air under their wings before they can fly.

If you have recurring issues with bats entering your home, inspect your attic to determine if you have a bat maternity colony.

4.2. Addressing House Bat Maternity Colonies

Most bats in the Northeast roost in secluded locations away from humans, but two species, the little brown bat and the big brown bat, often attract attention because they repeatedly roost in buildings. These bats once roosted in hollow trees but adapted to human structures after early settlers eliminated large expanses of forests. These ‘house bats’ typically roost in hot attics, which act as incubators for their growing pups.

Maternity colonies of little brown and big brown bats roost in attics.

Living in close proximity to humans presents unique challenges for the conservation of house bats. House bats have only one or two pups per year, so protecting maternity colonies is crucial for their survival. Destroying a maternity colony through chemical extermination or vandalism can significantly impact local bat and insect populations. While homeowners may view maternity colonies as a nuisance and mistakenly believe that extermination is the only solution, there is a safe, humane, and effective procedure for removing a bat colony from a building, called bat-proofing.

4.3. Identifying a Bat Colony

A simple way to determine if you are sharing your house with a bat colony is to enter the attic and look for roosting bats. During the day, bats will likely be roosting in narrow crevices in the attic walls, between the rafters, or tucked into the space between the rafters and roofing material. When you enter the attic, the bats will quickly retreat out of sight (rather than taking flight). If you cannot see them, listen for squeaking or scurrying sounds that will verify their presence.

If you are uncomfortable entering the attic when bats may be present, inspect the attic at night for bat droppings. The dry, black droppings, about the size of a grain of rice, accumulate in piles below areas where bats roost. Mouse droppings look similar but are scattered in small amounts throughout the attic. If you find bats living in your attic during the day or large accumulations of bat droppings, you likely have a maternity colony in your house.

Some homeowners, understanding the important role bats play in controlling insects, may choose to allow the colony to remain in the attic or eaves. In this case, it is essential to seal all openings that would give bats access to living spaces. This is particularly important for families with small children and pets.

If you have a bat colony in your attic and wish to remove it, use proper methods. Do not use chemical poisons or repellents. Poisons can scatter dead, dying, or disoriented bats throughout the house and neighborhood, increasing the risk of contact with children or pets. Repellents like moth balls or flakes, sulfur candles, or electromagnetic or ultrasonic sound devices do not permanently remove bats. Unless entrances are sealed, bats will return as soon as the repellents wear off. The best way to safely and permanently evict a maternity colony is to seal all of the colony’s entrances through bat-proofing.

5. Bat-Proofing Your Home

Bat-proofing a building involves sealing the bats’ entrance holes and providing an alternative roost, or bat box, for the maternity colony. It is typically a simple procedure that does not require professional skills or expensive materials. To bat-proof your home:

- Stage a “bat watch” to identify bat entrances.

- Seal the holes to prevent their entry.

- Provide an alternative roost, or bat box, for the colony to occupy.

5.1. Identifying Bat Entrances

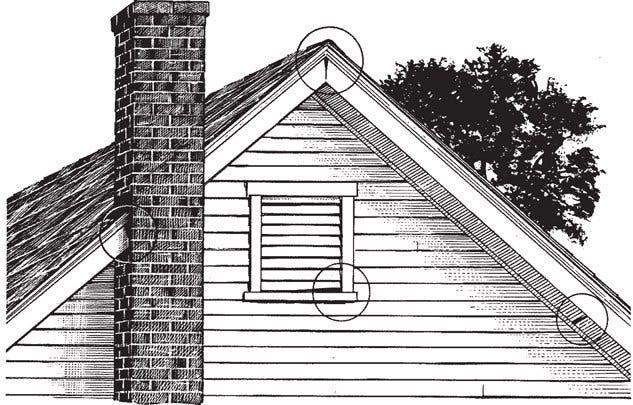

The first step is to locate the holes that bats use to enter and exit the attic. Bats often enter where joined materials have warped, shrunk, or pulled away from each other. Common access points include louvered vents with loose screening, the roof peak, and areas where flashing has pulled away from the roof or siding.

Bats usually enter at points where joined materials have warped or shrunk.

To identify which areas provide access, look for bat droppings on the side of the house below suspicious cracks or crevices. Entrances used for a long time may have a slight brown discoloration at the edges. Inspecting inside the attic can also reveal openings that need sealing. Bat droppings often accumulate below bat entrances and exits. During the day, turn off the attic lights and look for openings that allow outside light, and possibly bats, to pass through.

Staging a “bat watch” can help you locate the bats’ entrances. At dusk, station a person on each side of the building and watch as the bats exit. Once the first bats are seen leaving, focus on that area and watch for other exiting bats until you pinpoint their exit(s). Dawn is another good time to identify their entrances because returning bats will swarm around them before entering the building.

5.2. Sealing Bat Entrances

Once the bat entrances have been located, seal these openings. Use window screening or hardware cloth to cover louvered vents or large gaps and cracks. For smaller cracks, use expanding foam insulation or caulking compound. After hardening, these can be trimmed or painted as needed. Unlike mice, bats will not gnaw new holes, so sealing existing holes will keep them out. Most bat-proofing materials are available at local hardware or building supply stores. A listing of suppliers of bat exclusion products is included at the end of this guide.

5.3. Timing Your Bat-Proofing Efforts

Timing is crucial before bat-proofing. Because pups remain confined to the roost until they can fly, bat-proofing should never be done from late May through mid-July to prevent trapping young, flightless bats inside the building. Trapping pups would result in health risks and odor problems as they die and decay. Pups may also enter living areas seeking a way out, and females may frantically attempt to re-enter, even during daylight hours, to rejoin their young.

If bat-proofing must occur while pups are confined to the attic, due to, for example, roofing or siding work, allow one of the bats’ access points to remain open so that nursing females can enter and exit. After the pups can fly, install a one-way door to evict the bats. Once all bats have left, seal the remaining entrance.

The best time for bat-proofing is in the spring, before bats enter the roost, or in the fall, after the bats have left. If bat-proofing must be done while bats are inhabiting the building, it should be done by installing a one-way door after the pups can fly. One-way doors allow bats to leave but not re-enter.

Table 2. Timing of Bat-proofing

| Months | Methods for Bat-proofing |

|---|---|

| Jan.-April | Seal entrances before bats return to the building. |

| May-August | Watch bats to identify entrances. Do not seal openings. |

| August-Oct. | Install one way door(s). |

| Nov.-Dec. | Seal entrances once bats have left the building. (If you suspect bats are hibernating in the building, install a one-way door in Sept.-Oct.) |

Big brown bats occasionally overwinter in a building by hibernating in the attic or basement. If the homeowner suspects this, bat-proofing should be done by installing a one-way door in the fall, before hibernation begins, or in the spring, before the pups are born.

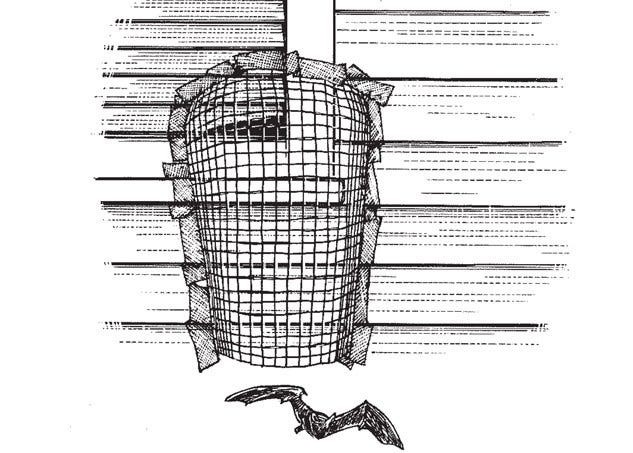

5.4. Using One-Way Doors

One-way doors are pieces of mesh or screening placed over a bat entrance to form a long sleeve or tent. These doors allow bats to exit at night but prevent their re-entry at dawn. One-way doors work because bats rely on their sense of smell, rather than vision, to locate their entrances. The bats will exit at the bottom, but when they return, they will land on the mesh near their entrance hole. They will smell their entrance through the mesh and crawl around, trying to find a way inside. The smell focuses their attention on that portion of the mesh, and the bats will not move to the opening at the bottom of the door to gain entrance. An easy-to-install one-way door is described below.

One-way doors allow bats to exit a building but prevent their reentry.

Installing One-way Doors

- Choose 1/4 to 1/2 inch wire screening or heavy plastic mesh to cover the bats’ points of entry. Cut the screening to cover the width of the hole and extend approximately three feet below it. The screening should project three-to-five inches clear of the hole, allowing bats to crawl between the screen and the building and exit at the bottom.

- Secure the mesh at the top and sides with duct tape or staples and leave the bottom open.

- Leave the door in place for at least three to four days, or until you are sure that all bats have left, then remove the one-way door and permanently seal the opening.

- Never use a one-way door during May through August, or young bats will be trapped inside and die.

5.5. Providing an Alternative Roost: Bat Boxes

Bat-proofing has two potential drawbacks. First, exclusion can be very stressful for a maternity colony. Prevented from using their traditional roost, bats may move into a nearby building, where they may be expelled again or even exterminated. Research indicates that displaced colonies will not relocate into buildings already housing other maternity colonies (Neilson 1991). An excluded colony cannot simply move down the road into a barn or church that already has bats. If a displaced colony cannot find a new roost, it may leave the area, contributing to declines in local bat populations (Humphrey and Cope 1976, Neilson 1991).

Second, homeowners may find it difficult to completely bat-proof their home. Bats can crawl through a crack as small as 1/2 by 1 1/4 inches, so persistent bats may find a way to reenter their traditional roost.

Bat boxes can solve both of these problems by providing alternative roosting sites for maternity colonies. When constructed properly, bat boxes can serve as suitable places for females to raise their pups. With bat boxes, the bats get a safe roosting site outside the home, while homeowners still benefit from the bats’ control of insects.

5.5.1. Bat Box Design

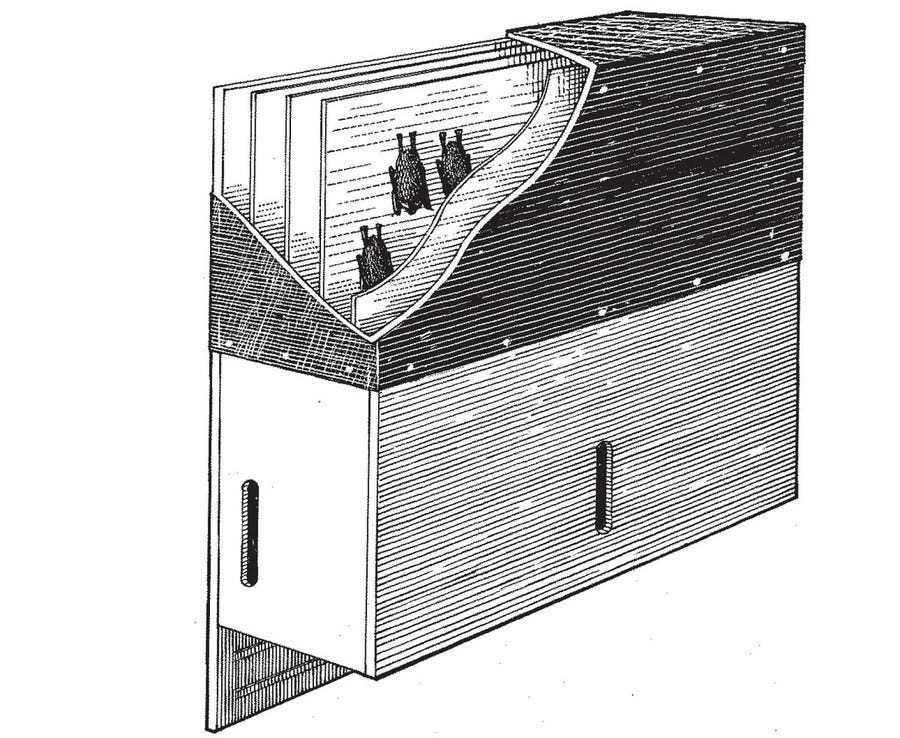

Size, interior construction, and temperature control are the most important design elements of bat boxes. Homeowners should consider building their own bat box, as commercial boxes may not provide the living space or roosting temperatures required by maternity colonies.

A bat box must be large enough to adequately house a maternity colony. Boxes should be at least 7 inches deep, 24 inches wide, and either 12 or 24 inches tall, depending on the size of the colony. Boxes 12 inches in height will house up to 100 bats, and boxes 24 inches in height will house as many as 200 bats. To house even larger colonies, you can join two boxes side-by-side, or you can install one large box that measures 14 to 21 inches from front to back.

The interior construction is important because maternity colonies have specific roosting chamber requirements. Baffles should be used to divide the interior space into multiple roosting crevices. The crevices should measure from 3/4 inches up to 1 1/2 inches in depth, with the majority in the 3/4 inch to 1 inch range. All baffles, interior surfaces, and the landing board below the box should be roughened with saw cuts to provide footholds for bats.

The interior of a bat box is divided into several roosting crevices.

The boxes must provide high incubation temperatures for pregnant females and growing pups. Staining the bat boxes dark brown or black enhances a box’s ability to absorb sunlight. The boxes must also have cooler areas for the bats to move into if temperatures rise too high. Tacking black roofing paper to the upper portions of the box and cutting ventilation slits into the lower sides and front will help to control interior temperature ranges.

5.5.2. Bat Box Placement

The amount of sunlight a bat box receives may be the most important factor to consider. In a study recently completed at Penn State, all bat boxes that received seven or more hours of direct sunlight successfully housed maternity colonies displaced by bat-proofing, while boxes that received fewer hours of direct sunlight were unsuccessful.

Bat boxes in Pennsylvania should face southeast or southwest to receive at least seven hours of direct sunlight during the spring and summer. In areas north of Pennsylvania, bat boxes may need more than seven hours of sunlight.

A bat box intended to house a displaced maternity colony should be placed on or very near the building in which the bats roosted, on an outside wall or chimney, or on a pole within 10 to 20 feet of the building. If placed on the building, the box should have at least 3 feet of open space under it, so that bats can enter and exit from the bottom. Avoid placing a bat box in an area heavily trafficked by people or where droppings will pose a problem. Bat boxes can also be placed on trees as long as they receive the required seven hours of sunlight. Whether on a building, pole, or tree, bat boxes should always be placed at least 10 to 15 feet above the ground.

Once the bats move into the box, it can gradually be moved farther away from the building in the fall or winter when bats are not present, moving no more than 20 yards per year.

5.5.3. Timing of Bat Box Installation

Ideally, bats should familiarize themselves with the bat box before being expelled from their traditional roost. Install the box in the winter or spring, then allow the bats to remain in the attic over the summer to investigate the box. Complete bat-proofing in the fall after the bats have left the building. The following spring, when the bats return, they will not be able to enter the building but will be familiar with the bat box and ready to inhabit it. This timing makes bat-proofing easier, as the bats should be less persistent in trying to re-enter the house.

If you cannot allow the bats to remain in the building for an additional summer, install the bat box and bat-proof the house before the bats arrive in April. The bats may not move into the unfamiliar box right away, but this option is still preferable to expelling a colony without providing an alternative roost.

Colonies identify their roosts, in part, by their smell, so it may help to scent the box with the colony’s droppings before installation. Gather a cup of droppings from the attic, mix them with water to make a slurry, and pour this mixture into the bat box. Allow the slurry to soak into the bat box before installing it. If scenting the box is not feasible, new boxes should at least be stored outside prior to installation, so the scent of new materials weathers out of them.

5.6. Bat Box Maintenance

Once bats move in, homeowners should never disturb a bat box during the day and should always watch the bats’ evening departure from a distance. Fencing off the area under the bat box will prevent people and pets from walking underneath it and minimize disturbance to the bats. Planting ornamental ground cover beneath the box can serve the same purpose and take advantage of the fertilizing quality of bat droppings.

Bat boxes require no maintenance when bats are present in the spring and summer. However, any active wasp nests can be removed with a long stick during cool mornings or evenings when wasps are less active (do not disturb the box if bats are present). In the fall and winter (after the bats have left the area), homeowners can inspect the box and make any necessary repairs. Also, old wasp nests should be removed at this time.

Occasionally, a bat pup may fall from the box. A fallen pup will die unless it is retrieved by its mother or crawls back into the box. If a grounded bat or bat pup must be handled, homeowners should wear thick work gloves. Children should be taught never to approach or pick up grounded bats.

5.7. Bat-Proofing Summary

The simplest procedure for expelling a maternity colony begins in the spring with the installation of a bat box. After that, the bats’ entrances into the building can be identified during the summer and sealed when the colony leaves in the fall. With patience and effort, you can exclude bats from your building permanently and successfully. With a bat box, you can take advantage of the bats’ ability to control insects while contributing to the protection and management of these beneficial mammals.

Table 3. Bat-proofing Schedule

| Months | Bat-proofing Schedule |

|---|---|

| Jan.-April | Install a bat box near the building in a location receiving seven hours of sunlight. |

| May-August | Allow bats to remain in the building and watch them exit at dusk to identify openings. |

| Sept.-April | Seal openings. |

6. Attracting Bats With Bat Boxes

Once people learn of the beneficial role that bats play in controlling insects, they often want to attract bats to their yards and gardens. It is difficult to predict whether a bat box will attract bats to hunt and feed in a desired area. Bat boxes provide shelter, but an ample supply of food and water is also needed to attract bats. Even in a location that has bats living nearby, a new bat box may remain vacant because the bats have other roosts in the area. Conversely, in areas where roosts are scarce, bats may move into a new bat box right away.

When trying to attract a maternity colony to an area, it is important to remember that these colonies are very loyal to their traditional roosts and will not readily seek out new roosts. This means that a bat box may sit unoccupied for years, even in areas that have several maternity colonies. However, an unoccupied box can always serve as an emergency shelter for a colony displaced from a nearby building. Also, a male bat may move into a bat box even when a maternity colony will not, and even one bat can consume nearly 3,000 insects per night.

A recent survey of bat box owners, conducted by Bat Conservation International, showed that the overall occupancy rate of bat boxes was approximately 52 percent. Success rates were somewhat lower for smaller boxes (32 percent) and somewhat higher for larger boxes (71 percent). The key to attracting bats to your property is to be patient at first and to experiment if your initial attempts are unsuccessful.

7. Addressing Bats and Public Health Concerns

7.1. Understanding Rabies Risks

Rabies is the most significant public health concern associated with bats, but its impact is often overstated. All mammals are susceptible to this potentially fatal disease, which is caused by a virus that attacks the central nervous system.

Animals with rabies will experience either a “furious” stage, in which they attack anything in their path, or a “dumb” stage, in which they become progressively paralyzed before death. Bats can experience either of these stages, although most infected bats display behavior associated with the dumb stage of rabies (Constantine 1979). Once symptoms of rabies appear, bats usually become immobilized within two days and die within four days (Fenton 1992).

The incidence of rabies in the wild bat population is low, and the spread of rabies within individual colonies appears to be very rare (Constantine 1979). Scientific surveys of wild bats in the United States and Canada indicate that the incidence of rabies in clinically normal bats is less than 0.5 percent (Fenton 1992). However, of the sick, dead, or suspect bats submitted to health departments for testing, approximately 2-5 percent test positive for rabies. Thus it is important to take precautions when handling grounded bats. Most human exposure to infected bats results from careless handling of grounded bats.

Almost everyone recognizes the need to seek immediate medical attention after an unprovoked attack by a bat (or any other animal). However, a bat lying helplessly on the ground will often arouse humanitarian instincts. The person trying to help the grounded bat may get bitten and ignore the bite because it occurred in self-defense. Regardless of the circumstances, anyone bitten by a wild animal should immediately wash the wound with soap and water and seek medical attention.

Of course, not all grounded bats are rabid. For example, young pups often become grounded when learning to fly. However, bats that can be caught, particularly grounded bats or bats found in unusual places, are more likely to be sick than others. Always handle all bats with leather work gloves, and warn children never to approach or pick up grounded bats. Also, cats and dogs, which come into contact with bats and other wild animals far more often than their owners, should be immunized regularly for rabies.

There is little evidence to support the notion that bats with rabies contribute to outbreaks of the disease in other wild animals (Tuttle and Kern 1981). The World Health Organization’s Expert Committee on Rabies found no evidence of natural bite transmission from insect-eating bats to carnivores (Tuttle and Kern 1981). Laboratory experiments showed that animals could be infected with rabies if they ate large amounts of infected tissue (Fenton 1992). Although the significance of this finding to animals in the wild is unknown, it again highlights the need to immunize dogs and cats.

Humans and other mammals have contracted rabies through airborne transmission, but this happened in a large southwestern cave harboring about 13 million bats. The cave’s unique conditions of high temperature and humidity and air saturated with the bats’ saliva and urine probably contributed to the airborne transmission of the virus (Fenton 1992). Most bat roosts do not have the right conditions for transmitting rabies through the air, and there are no records of airborne transmissions from maternity colonies living in buildings (Fenton 1992).

Rabies Precautions

- Bats of all sizes will bite in self-defense, but they almost never attack people.

- If you must handle a bat, take precautions to minimize the chance of being bitten. By wearing leather gloves and scooping a grounded bat into a coffee can or some other container, you make it virtually impossible for a bat to bite you.

- If you are bitten by a bat, immediately wash the bite with soap and water and see a physician. If the bat is captured, it should be killed (without destroying the head) and submitted for testing. If there is any possibility that you have been infected, the physician will recommend rabies shots. Today, most people receive the rabies vaccine in a series of five relatively painless shots in the arm administered during a one month period.

- People usually know when they are bitten by a bat. However, because bats have very small teeth, the bite is rarely obvious. Consequently, if a bat is found in the same room with a young child or mentally incapacitated person or even a very heavy sleeper, and the possibility of a bite cannot be eliminated, rabies treatment should be given.

7.2. Addressing Histoplasmosis Concerns

Histoplasmosis is an airborne disease caused by a microscopic fungus that occurs in soil and in the nitrogen-rich droppings of birds and bats (Tuttle and Kern 1981, Greenhall 1982, Fenton 1992). A dry cough and other flu-like symptoms are the usual signs of histoplasmosis, often mistaken for influenza. While histoplasmosis often does not produce any symptoms, severe symptoms such as high fever, problems with vision, and life-threatening complications occasionally do occur (Greenhall 1982, Fenton 1992).

The fungus that causes the disease occurs naturally in soils throughout warmer regions of the world, including parts of North America (Fenton 1992). The fungus is also associated with bat droppings, called guano, which accumulates in caves where bats live in summer months. Hibernating bats do not produce guano and therefore do not deposit the fungus in caves where they hibernate (Fenton 1992). In the eastern United States, surveys in buildings that had accumulations of guano from several colonies of big brown and little brown bats produced no evidence of the fungus causing histoplasmosis (Fenton 1992).

Homeowners should still take safety precautions against inhaling any particles that may contain the fungus, particularly if large amounts of bat droppings are to be disturbed in an attic. To limit the amount of airborne particles, the droppings should be vacuumed rather than swept or shoveled. Homeowners should also use a properly fitted respirator capable of filtering particles as small as two microns in diameter to further minimize the risk of exposure (Tuttle and Kern 1981).

7.3. Managing Bat Parasites

Like other animals, bats are hosts to several internal and external parasites. Most of these parasites are specialized and cannot survive away from the bats, so they pose little threat to humans and other animals (Fenton 1992). A species of bedbug, resembling the species that feeds on humans, lives on the bats and in their roosts. However, reports of these bedbugs biting humans or domestic animals are rare. Once a bat colony is evicted from a building, any parasites that remain behind may move around the attic (and possibly the house) in search of bats. Fortunately, these parasites usually die quickly when separated from the bats.

A homeowner can sprinkle diatomaceous earth in the roost area to eliminate any parasites that may remain after the bats are evicted. This organic powder,