Originally conceived to navigate the depths of the Adirondack wilderness, the Adirondack Guide Boat stands as a testament to ultralight engineering. These meticulously crafted vessels, in their original planked form, weighed a mere seventy pounds yet boasted a carrying capacity of a thousand pounds. This remarkable design allowed for seamless passage through the numerous portages, connecting the myriad lakes and rivers sculpted by glaciers within these mountains.

My personal foray into the world of the guide boat began after an enlightening few weeks spent rowing an eighteen-foot sailboat in the Sea of Cortez. As a lifelong devotee of kayaking, I was taken aback by the profound enjoyment rowing offered and equally impressed by the seaworthiness of a rowboat. I envisioned a future filled with rowing upon my return home. However, time slipped by – a year, then two – and eventually, I sold the sailboat, having used it only once since my Mexican adventure. The crux of the issue was convenience: when the urge to boat struck, the hassle of dealing with a trailer paled in comparison to the simplicity of hoisting a kayak onto the car and being on the water in under thirty minutes. The kayak invariably won.

Then, a friend’s suggestion piqued my interest in the Adirondack guide boat. I procured some plans and books for research, sought advice from experts, and, crucially, enlisted a student to maintain my motivation throughout the project. Had I been a traditional boat builder, I might have opted for spruce crooks, thin planking, 2100 brass screws, and 4000 individually clench-nailed copper tacks. However, as a proponent of skin-on-frame construction, I naturally gravitated towards this method. While most skin boats are adaptations, the guide boat’s inherently perfect form made me hesitant to deviate from its original lines. Instead, I committed to building my boats as faithful replicas of the original design, employing a similar process.

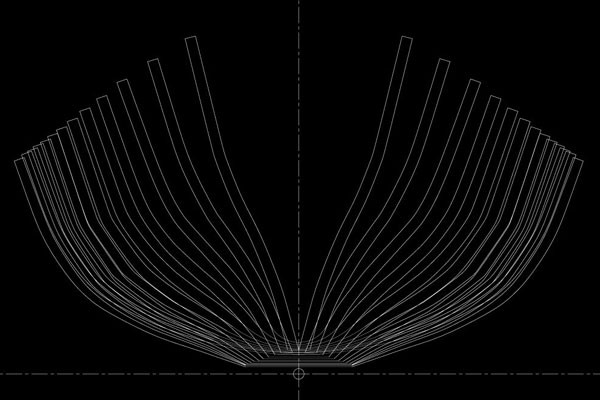

Our starting point was a table of offsets, a coordinate system defining the boat’s lines. I say “we” because I shrewdly outsourced the laborious task of hand lofting to my girlfriend Jackie, a skilled draftswoman, who undertook the days of meticulous computer lofting. It truly pays to have a draftsperson at hand! Next, we created what guide boat builders prize most: a set of rib forms. These forms serve as templates for laminations (or natural wood crooks) to accurately reproduce the boat’s shape.

Day 1: We initiated the rib construction by laminating cedar strips over the forms. This process shapes the initial thick ribs of the Adirondack guide boat.

Day 2: Using a table saw, we carefully sliced these thick ribs lengthwise. Each lamination yielded four thin cedar ribs, ready for the Adirondack guide boat frame.

Also on Day 2, we laid out the flat bottom board. This board serves as the foundational spine of the guide boat, providing a base for the ribs and the overall structure.

Day 3: We proceeded to screw the ribs onto the bottom board. Peter, my elusive apprentice, provided invaluable assistance, though he remained camera-shy throughout the process. This step solidifies the basic skeletal structure of the Adirondack guide boat.

With the ribs and stems securely mounted, we turned the boat right-side up. It was then fixed to a jig, a crucial step to maintain the rocker and plumb of the stems, ensuring the boat’s designed curvature and vertical alignment.

Day 4: Sheer strakes were next on the agenda. We laminated three red cedar boards to create a robust two-inch sheer strake, essential for the gunwale of the Adirondack guide boat.

The laminated strakes were then sliced using the table saw and subsequently screwed to the ribs and stems. This process firmly establishes the gunwales, defining the boat’s upper edges.

For added security and peace of mind, I incorporated a lashing at the strake ends, reinforcing the gunwale’s integrity.

Day 5: We flipped the boats over and proceeded to clamp stringers onto the ribs. These stringers were meticulously fastened with carefully piloted stainless ring nails. The stringers measured 7/16 square, while the ribs were 5/16 x 3/4 on edge, dimensions crucial for the guide boat’s lightweight strength.

The stringers were faired seamlessly into the stems and then lashed, a straightforward process that integrates these structural elements.

Day 6: We finalized the frames by adding support structures for the decks and then applying oil to the wood, both protecting and enhancing the boat’s wooden components.

Day 7 marked the skinning phase. A lightweight ballistic nylon skin was laid over the frame, then cut and sewn up the stems, encasing the frame in its durable outer layer.

Subsequently, the skin was stapled to the frame. The staples were then concealed beneath a fir gunwale. To complete the skinning process, the nylon was saturated with a robust two-part polyurethane, providing a tough, waterproof finish to the Adirondack guide boat.

The following week was devoted to intermittent finishing work, including crafting these seats. I expedited these details, resulting in finish work that is admittedly cruder than that of original guide boats. However, I deemed it fitting for a boat constructed in such a rapid timeframe.

Hand-caning the seats proved to be a less enjoyable task, but fortunately, I had assistance to expedite this traditional element.

The finished seat, a testament to traditional craftsmanship incorporated into the skin-on-frame Adirondack guide boat.

My approach to deck and end protection involved marine plywood, brass flat stock, and bronze rings – admittedly crude but undeniably effective. The smaller boat was also fitted with a sliding seat, enhancing rowing efficiency.

Traditional guide boat oars are permanently pinned, allowing the rower to quickly drop the oars to manage fishing lines or hunting gear. I appreciated these non-feathering oars and adapted readily to the cross-armed rowing stroke necessitated by the overlapping handles. Traditional guide boat hardware can cost around $250; to economize, I opted for a $50 set of pinned bronzed oarpins.

I am indebted to my friend Alec for the layout of these traditional guide boat oars. Their correct function hinges on lightweight construction and precise shaping to maintain structural integrity. He expertly shaped most of the oars while I concentrated on finishing the boats.

The finished products, launched just two weeks after the project’s inception.

Beautiful. I’ve become so enamored with the thirteen-footer that I’m reluctant to return it to Peter (the phantom apprentice). Of course, the fifteen-footer is equally impressive.

Getting ready for the launch, Alec steadies the boat as Jackie settles in, ready for their maiden voyage.

Then, with a bold leap of faith, Alec lunges forward and pushes off, showcasing the boat’s stability and ease of launching.

Alec in the thirteen-footer, this boat could comfortably accommodate another passenger, making it ideal for shared rowing experiences.

Rowing these boats was a revelation – swift, silent, and remarkably powerful. I can only describe the experience as addictive. Even carrying them was a pleasure. The thirteen-footer weighs a mere thirty-one pounds, and the fifteen-footer tips the scales at forty-two pounds. The thirteen-footer, constructed entirely of red cedar, feels remarkably stiff. I anticipate the fifteen-footer would benefit from slightly more framing, potentially adding no more than five pounds to its weight. The material cost for each boat was approximately nine hundred dollars.

Building the skin-on-frame Adirondack guide boat has instilled in me a profound respect for the meticulous craftsmanship of the original designs. It is, without a doubt, the most beautiful and rewarding creation I have ever built in my life. Sincere gratitude to The Adirondack Museum, Geoff Burke, Rob Frenette, Ben Fuller, Jackie, Alec, and Peter for their invaluable contributions. I eagerly anticipate sharing this boat building experience in a class this summer.