Alt text: Greater honeyguide bird eating beeswax in Mozambique, illustrating honeyguide bird behavior.

For generations, a captivating tale of cross-species cooperation has circulated among naturalists and wildlife enthusiasts: the story of the honey guide bird and the honey badger. This narrative paints a picture of mutual benefit, where the honeyguide bird, with its craving for beeswax, enlists the brute strength of the honey badger to raid bees’ nests. The bird guides the badger to the hive, the badger tears it open, and they both share the spoils. But is this charming anecdote of animal partnership truly reflective of reality when examining the Honey Guide Bird/badger Relationship Type?

While the honeyguide bird’s ability to lead humans to bees’ nests is well-documented and frequently observed, the evidence for a similar cooperative relationship with honey badgers has remained largely anecdotal and uncertain. Dr. Jessica van der Wal from the University of Cape Town, the lead author of a recent study, explains, “While researching honeyguides, we have been guided to bees’ nests by honeyguide birds thousands of times, but none of us have ever seen a bird and a badger interact to find honey. Evidence for bird and badger cooperation in the literature is patchy – it tends to be old, second-hand accounts… So we decided to ask the experts directly.”

To investigate the veracity of this long-standing belief about the honey guide bird/badger relationship type, a team of researchers from nine African countries, under the guidance of the Universities of Cambridge and Cape Town, embarked on a comprehensive study. They conducted nearly 400 interviews with honey-hunters across Africa, individuals with extensive firsthand knowledge of both species and their interactions with the environment. These communities, deeply connected to the land, have been harvesting wild honey for generations, often with the assistance of honeyguide birds.

The survey revealed a widespread skepticism regarding the purported honey guide bird/badger relationship type. Across the 11 communities surveyed, a significant majority expressed doubt that honeyguide birds and honey badgers engage in mutual assistance to access honey. In fact, 80% of respondents stated they had never witnessed any interaction between the two species.

However, the responses from three communities in Tanzania presented a notable exception. Within these communities, a considerable number of people reported observing instances of honeyguide birds and honey badgers cooperating to obtain honey and beeswax from bees’ nests. These sightings were particularly prevalent among the Hadzabe honey-hunters, with 61% of them claiming to have witnessed this interspecies cooperation.

Alt text: Honey badger consuming beeswax and honeycomb captured by trail camera, showcasing honey badger feeding habits.

Dr. Brian Wood from the University of California, Los Angeles, a co-author of the study, highlights the unique perspective of the Hadzabe: “Hadzabe hunter-gatherers quietly move through the landscape while hunting animals with bows and arrows, so are poised to observe badgers and honeyguides interacting without disturbing them. Over half of the hunters reported witnessing these interactions, on a few rare occasions.” Their detailed observations offer valuable insights into the potential nuances of the honey guide bird/badger relationship type in specific geographical locations.

To further analyze the feasibility of this cooperation, the researchers meticulously reconstructed the sequence of events that would be necessary for honeyguide birds and honey badgers to effectively collaborate. While certain steps, such as a honeyguide bird spotting and approaching a badger, appear plausible, others remain questionable. The idea that a honeyguide bird could effectively communicate with a badger through chattering, and that the badger would then follow the bird to a bees’ nest, raises doubts. Honey badgers are known for having relatively poor hearing and eyesight, characteristics not ideally suited for following the auditory and visual cues of a small bird.

This raises the possibility that the cooperative honey guide bird/badger relationship type might not be universally present across all honey badger populations. The researchers suggest that perhaps only specific Tanzanian honey badger populations have developed the necessary skills and learned behaviors to engage in this type of cooperation with honeyguide birds. These skills and knowledge could then be transmitted across generations, leading to localized instances of this fascinating interspecies partnership. Another possibility considered is that badger and bird cooperation might occur in more regions of Africa than currently documented, but simply remains unobserved due to the challenges of witnessing such interactions in the wild.

Alt text: Honey badger eating honeycomb in Mozambique reserve, depicting honey badger diet and foraging behavior.

Dr. Dominic Cram from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, a senior author of the study, points out the difficulty in observing this interaction due to human presence: “The interaction is difficult to observe because of the confounding effect of human presence: observers can’t know for sure who the honeyguide bird is talking to—them or the badger.” The presence of humans, who also engage in honey hunting with honeyguides, complicates the observation and interpretation of these bird-badger interactions.

Despite these challenges, the consistent reports from multiple Tanzanian communities cannot be easily dismissed. “But we have to take these interviews at face value. Three communities report to have seen honeyguide birds and honey badgers interacting, and it’s probably no coincidence that they’re all in Tanzania,” Dr. Cram concludes. The study underscores the importance of incorporating local ecological knowledge and engaging with communities who have long-standing relationships with their environment. Integrating both scientific investigation and traditional ecological wisdom is crucial to deepen our understanding of complex ecological interactions like the honey guide bird/badger relationship type.

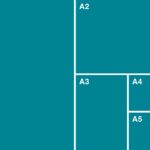

The greater honeyguide bird ( Indicator indicator ) has a long history of interaction with humans across Africa, acting as a natural guide to bees’ nests. Wild honey is a valuable resource, providing a significant source of calories, and the beeswax discarded by honey hunters is a prized food source for honeyguides. Humans have learned to interpret the calls and behaviors of honeyguides, engaging in a form of interspecies communication to locate bees’ nests.

While humans, with their tools and control of fire, are highly efficient partners for honeyguides, honey badgers present a different dynamic. Honey badgers may anger bees and face aggressive defenses, sometimes even resulting in fatal stings for honeyguide birds attempting to partake in the disrupted hive. This raises questions about the evolutionary origins of the honeyguide’s guiding behavior.

Alt text: Honey hunter harvesting bees’ nest in Mozambique, illustrating human-honeyguide bird cooperation in honey collection.

Dr. Claire Spottiswoode from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology, another joint senior author, suggests an intriguing possibility: “Some have speculated that the guiding behavior of honeyguides might have evolved through interactions with honey badgers, but then the birds switched to working with humans when we came on the scene because of our superior skills in subduing bees and accessing bees’ nests. It’s an intriguing idea, but hard to test.” The honey guide bird/badger relationship type might represent an earlier evolutionary stage of honeyguide behavior, later adapted to capitalize on the even more advantageous partnership with humans.

The study highlights that while the classic Disneyesque vision of a widespread honey guide bird/badger relationship type may be overly simplistic, the reality is likely more nuanced and geographically specific. The firsthand accounts from Tanzanian communities, particularly the Hadzabe, offer compelling evidence that some form of cooperation may indeed exist in certain areas. Further research, integrating both scientific observation and the invaluable insights of local communities, is needed to fully unravel the complexities of this fascinating interspecies dynamic and the true nature of the honey guide bird/badger relationship type.