Compliance, a critical skill for success, especially in educational settings, can be significantly improved through various reinforcement strategies. This article explores the nuances of compliance, specifically focusing on how negative reinforcement, either alone or in combination with positive reinforcement, affects task compliance within a guided compliance procedure. Understanding these mechanisms can lead to more effective interventions for individuals struggling with non-compliance.

Teachers recognize compliance as a foundational skill (Walker, 1986). Consistent non-compliance can hinder skill development, strain family life (Wierson & Forehand, 1994), and contribute to behavioral issues (Merchant, Young, & West, 2004). Interventions that effectively increase compliance are therefore essential. While studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of positive reinforcement alone (DeLeon, Neidert, Anders, & Rodriguez-Catter, 2001; Lalli et al., 1999) or in combination with negative reinforcement (Kodak, Lerman, Volkert, & Trosclair, 2007; Piazza et al., 1997) in boosting compliance and curbing destructive behaviors, the independent effects of negative and positive reinforcement on compliance warrant closer examination. The relative effects of these reinforcement types, when applied both separately and jointly, remain a key area of investigation. This study delves into these separate and combined effects on task compliance.

Method

The study involved a 14-year-old boy named Nate, diagnosed with Down syndrome, who exhibited noncompliance with caregiver demands. Sessions were conducted in a controlled environment.

Participant and Setting

Nate, the participant, struggled with compliance across various tasks. The sessions were held in a designated room equipped with necessary materials, including a CD player for positive reinforcement conditions and instructional materials like paper balls (“trash”) and a trash can.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Compliance was measured by observing whether Nate completed the designated task (throwing away trash) within 5 seconds of a prompt (vocal or modeled) and before any physical prompting was required. The frequency of compliance and task presentations were tracked using a computer-based data collection program, calculating the percentage of compliance by dividing compliant actions by the total tasks presented. Interobserver agreement was calculated at 95%.

Procedure

The study employed a graduated prompting hierarchy, including vocal, modeled, and physical prompts, with consequences varying based on the condition. Sessions lasted 10 minutes.

During the initial analysis, the experiment began with a baseline phase where brief praise was given for compliance, followed by three conditions: break (praise and a 60-second break), music (praise and 60-second access to preferred music), and combined (praise, break, and music). The second analysis was designed to see if the number of task presentations impacted compliance across reinforcement contingencies.

Results and Discussion

The study found that the combined contingency of positive and negative reinforcement was most effective.

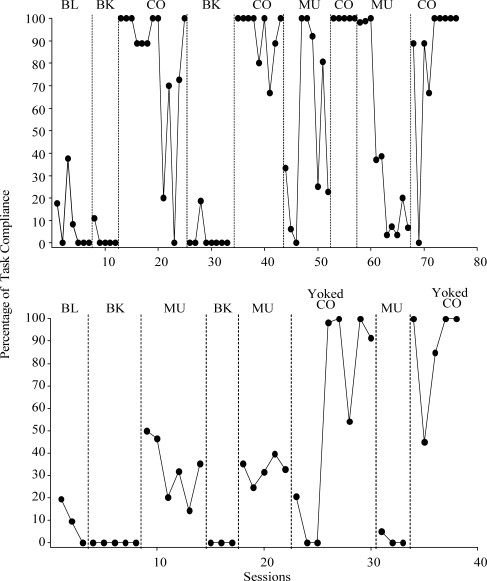

Figure 1. Nate’s Task Compliance Percentage

Nate's percentage of task compliance across the baseline (BL), break (BK), music (MU), and combined (CO) conditions of the first analysis (top) and second analysis (bottom)

Nate's percentage of task compliance across the baseline (BL), break (BK), music (MU), and combined (CO) conditions of the first analysis (top) and second analysis (bottom)

During the initial analysis, the combined contingency yielded the highest compliance levels, achieving 100% in the last five sessions. The second analysis reinforced these findings, suggesting that the combined approach was superior in boosting compliance, irrespective of the number of tasks presented.

The results suggest that a combination of both positive and negative reinforcement was most effective for increasing one participant’s compliance to simple tasks. One possible explanation for these results is that the combination of both contingencies increased the individual value of each reinforcer. This may also resemble naturally occurring consequences that maintain noncompliance. For instance, when a child is noncompliant following a parent instruction and the parent allows escape from that instruction, the child likely has access to preferred items rather than sitting without engaging in any activity (as arranged in the break condition). These results are consistent with previous research in which a combination of positive and negative reinforcement was most effective for reaching treatment goals (e.g., DeLeon et al., 2001; Kodak et al., 2007; Lalli et al., 1999; Piazza et al., 1997). However, the current study is noteworthy in that previous research evaluated these contingencies for affecting levels of escape-maintained problem behavior, whereas the current investigation examined the effects of these contingencies on compliance.

Understanding Negative Reinforcement in Compliance

The break condition represents negative reinforcement. How Is Compliance Negatively Reinforced In A Guided Compliance Procedure? In this context, compliance resulted in the removal of the task demand for a short period. This removal of an aversive stimulus (the task itself) increases the likelihood of compliance in the future. The participant is more likely to comply with the task next time to avoid having to continuously engage with the task. This is the core principle of negative reinforcement. The study further emphasizes that this negative reinforcement is more effective when paired with positive reinforcement, like access to music.

Conclusion

This study highlights the effectiveness of combining positive and negative reinforcement to improve task compliance. While both reinforcement types showed some impact independently, their combined effect resulted in the most significant and stable improvements. This approach suggests that understanding and strategically applying reinforcement contingencies can substantially enhance compliance in individuals who struggle with it. The most effective strategy leverages both positive and negative reinforcement to optimize outcomes. This research paves the way for developing tailored interventions that address the complexities of compliance behavior.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Grant R03MH083193 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. We thank Ty Starks for his assistance with data collection and Heather Kadey for her comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- DeLeon, I. G., Neidert, P. L., Anders, B. M., & Rodriguez-Catter, V. (2001). The use of positive and negative reinforcement to establish responding in a child with feeding refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34(4), 555–558.

- Kodak, T., Lerman, D. C., Volkert, V. M., & Trosclair, N. (2007). Further analysis of brief stimulus fading for the treatment of escape-maintained aggression. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(3), 459–474.

- Lalli, J. S., Mace, F. C., Wohn, T., & Livezey, K. (1999). Functional assessment and treatment of escape-maintained problem behavior: A one-session format. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(2), 233–244.

- Lomas, J. E., Fisher, W. W., & Kelley, M. E. (2010). Abolishing operations: A review and commentary. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 43(2), 329–340.

- Merchant, D., Young, K. R., & West, R. P. (2004). The effects of a self-management package on the independent work skills of middle school students with behavioral disorders. Education and Treatment of Children, 27(2), 149–166.

- Piazza, C. C., Fisher, W. W., Hanley, G. P., Hilker, K. A., Kurtz, P. F., & Sherer, M. R. (1997). Treatment of multiple topographies of escape-maintained behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(3), 449–464.

- Roane, H. S., Vollmer, T. R., Ringdahl, J. E., & Marcus, B. A. (1998). Staff training: Evaluation of a behavior-analytic approach. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(4), 685–688.

- Walker, H. M. (1986). The assessment for integration into mainstream settings of children with behavior disorders. In R. J. McMahon & R. D. Peters (Eds.), Behavioral disorders of childhood (pp. 3–29). New York: Plenum Press.

- Wierson, M., & Forehand, R. (1994). Parent behavioral training for child noncompliance: Is there anyone who can’t be trained?. Behavior Therapy, 25(1), 145–160.