Interviewing suspects is a critical aspect of police investigation, demanding a blend of skills, ethical conduct, and legal awareness. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of how to conduct effective police suspect interviews, focusing on best practices, legal considerations, and the PEACE framework. It is designed to enhance understanding and proficiency in investigative interviewing for law enforcement professionals and anyone interested in the intricacies of criminal investigations.

Establishing Professionalism and Integrity in Interviews

The cornerstone of any successful police interview is the interviewer’s professionalism and integrity. Building trust and ensuring fairness are paramount to obtaining accurate and reliable information. A suspect is more likely to cooperate and provide truthful accounts when they perceive the interviewer as competent, ethical, and respectful.

Key elements of professionalism and integrity include:

- Fair Treatment: Every interviewee, regardless of their status as a suspect, victim, or witness, must be treated fairly and in accordance with all applicable laws and guidelines. This includes adhering to principles of equality and human rights.

- Impartiality: Personal biases, opinions, or beliefs must never influence how an interviewer interacts with or assesses an interviewee. Maintaining objectivity is essential for unbiased information gathering.

- Methodical Approach: A structured and methodical approach benefits both the interviewer and the interviewee. This involves thorough planning, preparation, adherence to the interview plan, and ensuring logical connections between questions and answers. The PEACE interview model provides a robust framework for this structured approach.

- Personal Style and Rapport: The interviewer’s style significantly impacts the interviewee’s motivation to be accurate and forthcoming. Establishing rapport involves genuine openness, approachability, and interest in the interviewee’s perspective and well-being.

- Appropriate Interview Location: The interview environment can influence the dynamic between interviewer and interviewee. Consideration should be given to how the location, particularly the formality of a police station interview room, might affect different individuals, especially vulnerable witnesses or victims.

- Awareness of Suggestibility: Interviewers must be mindful of suggestibility, where interviewees might be influenced to say what they believe the interviewer expects. Vulnerable individuals, such as juveniles or those with learning disabilities, are particularly susceptible and require additional safeguards.

Core Principles and Ethics in Investigative Interviewing

The approach to investigative interviewing is underpinned by a commitment to quality and ethical practices. Professional interviewing aims to secure a complete and accurate account, achieved by asking pertinent questions within a framework of principles designed to guide investigators.

Benefits of adhering to these principles:

- Enhanced Public Confidence: Professional interviews yield high-quality evidence, essential for both convicting the guilty and exonerating the innocent. This process builds public trust in law enforcement and the justice system, particularly among victims and witnesses.

- Consistent Performance: Investigative interviews occur in diverse settings, from police stations to crime scenes, homes, and public spaces. Mastering investigative interviewing techniques ensures effective outcomes regardless of the environment.

- Victim and Witness Support: Victims and witnesses often experience distress, fear, or suspicion. Skilled interviewers can provide reassurance and calm, facilitating accurate and detailed accounts.

- Effective Suspect Engagement: While suspect interviews often take place in formal settings, assuming all suspects will be uncooperative is inaccurate. Many suspects, when faced with strong evidence and skillful interviewing, may admit guilt, contributing to efficient case resolution.

Seven Key Principles of Investigative Interviewing

These principles guide investigators in using the PEACE framework effectively, complying with legal standards, and engaging constructively with legal advisors.

Principle 1: Accurate and Reliable Accounts

The primary goal is to obtain accounts from victims, witnesses, or suspects that are both accurate and reliable.

- Accuracy: Information should be comprehensive, without omissions or distortions, presenting a true representation of events.

- Reliability: The information must be truthful and withstand scrutiny, such as in court proceedings. Reliable accounts form a solid basis for further investigation, opening new avenues of inquiry and informing subsequent questioning.

Principle 2: Fairness and Compliance

Investigators must conduct interviews fairly, adhering to the Equality Act 2010 and the Human Rights Act 1998.

- Absence of Prejudice: Interviewers should approach each interview without preconceived notions. It is crucial to be open to believing the account provided initially, while employing critical thinking and sound judgment, rather than personal biases, to assess its veracity.

- Protection of Vulnerable Individuals: Individuals with identified or perceived vulnerabilities require special consideration and protection. Extra safeguards must be in place to ensure their rights and well-being are protected throughout the interview process.

Principle 3: Investigative Mindset

Investigative interviewing should be driven by an investigative purpose.

- Verification and Corroboration: Accounts obtained must be consistently checked against existing knowledge and verifiable facts. The aim is to use interview information to advance the investigation by establishing facts, aligning with the overall investigative strategy.

- Objective Setting: Interviewers should define clear objectives for each interview with victims, witnesses, or suspects. These objectives should aim to confirm or refute existing information and to fill gaps in the investigative narrative.

Principle 4: Broad Questioning Range, Ethical Style

Investigators are permitted to ask a wide range of questions to uncover information and evidence relevant to the investigation.

- Evidentiary Flexibility: Investigative interviews are distinct from courtroom examinations. Interviewers are not bound by the strict rules of evidence applicable in court, allowing for a broader scope of questioning.

- Fair and Lawful Conduct: Despite the broad questioning scope, the interview style must remain fair and not oppressive. Compliance with the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) and its Codes of Practice is mandatory, alongside considerations for equality and human rights.

- Definition of Oppression: As defined in R v Fulling [1987], oppression involves the burdensome, harsh, or wrongful exercise of authority or power, or unjust and cruel treatment that implies impropriety by the interviewer.

Principle 5: Recognizing Early Admissions

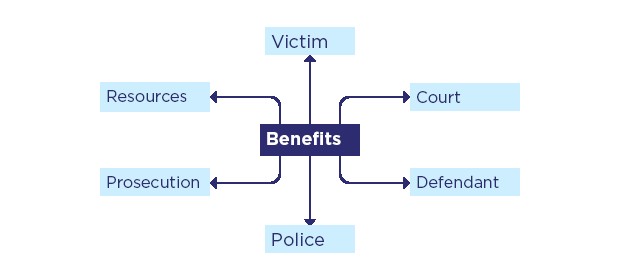

Early admissions of guilt have significant positive impacts within the criminal justice system.

- Benefits for Victims: Early admissions provide victims with the opportunity to seek compensation and see a swift acknowledgment of the offense by the justice system.

- Benefits for the Court: Courts gain a clearer and more accurate understanding of the offense, enabling more appropriate sentencing and potential savings from reduced court proceedings.

- Benefits for Defendants: Defendants who admit guilt early may receive sentence reductions, access to rehabilitation programs, and the chance to resolve matters quickly, avoiding further legal complications.

- Benefits for Police: Early admissions yield valuable intelligence, improve crime detection rates, and provide a more complete picture of criminal activities, aiding future investigations and crime prevention efforts.

- Benefits for Prosecution: Prosecutors gain a fuller understanding of the offender’s history, informing decisions on public interest, bail, and sentencing considerations.

- Resource Efficiency: Efficient use of resources and improved public confidence in the criminal justice system are additional benefits of early guilty pleas.

Principle 6: Persistence in Questioning

Investigators are not required to accept the first answer given. Persistence in questioning is acceptable and often necessary to obtain a complete and reliable account.

- Reasons for Persistence: Persistence is justified when there is reason to believe the interviewee is not being truthful or when further information is likely to be available.

- Ethical Persistence: Persistence in questioning must be balanced with caution to avoid being unfair or oppressive, adhering to PACE Code C guidelines.

Principle 7: Questioning Suspects Exercising Right to Silence

Even when a suspect chooses to remain silent, investigators still have a responsibility to ask questions.

- Right to Question: This principle upholds the investigator’s right to question anyone believed to have information relevant to an investigation.

- Adverse Inferences: While suspects have the right to silence, they are cautioned that exercising this right may lead to adverse inferences, particularly under the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 (CJPOA), regarding failure to account for objects, substances, marks, or presence at a specific location.

The PEACE Framework: A Model for Investigative Interviewing

The PEACE framework is a widely recognized and effective model for conducting investigative interviews. It comprises five phases, each designed to facilitate ethical and effective information gathering.

1. Planning and Preparation (P)

This initial phase is crucial for setting the stage for a successful interview. Thorough planning can significantly influence the outcome of the interview and the overall investigation.

- Planning Session: Conduct a planning session to review all available information and define key issues and objectives, even when an immediate interview is necessary.

- Interview Plan Creation: Document a detailed interview plan, considering the objectives of the interview and the specific points needed to be covered.

- Interviewee Characteristics: Consider individual characteristics of the interviewee, such as age, cultural background, religion, domestic circumstances, health (physical and mental), disabilities, prior police contact, and gender. These factors can influence interview timing, the need for support persons, and communication approaches.

- Practical Arrangements: Address practical considerations, including visiting the scene, searching premises, interview location, interviewer roles, timing, necessary equipment, exhibits, and comprehensive knowledge of the offense.

- Written Interview Plan: Prepare a written plan summarizing interview aims, providing a questioning framework, and enhancing interviewer confidence and flexibility. This plan should cover custody time, topics to be covered, elements of the offense, potential defenses, exhibit introduction, evidence against the suspect, and planning for various scenarios like prepared statements or adverse inferences.

- Multiple Interviewers: Clearly define roles for each interviewer in the plan, typically designating a lead interviewer and a note-taker to maintain structure and avoid unstructured questioning.

2. Engage and Explain (E)

Building rapport and clearly explaining the interview’s purpose are essential first steps.

- Engagement: Initiate conversation by engaging the interviewee, especially important if they are not previously known to the police. Active listening helps establish and maintain rapport, manage conversation flow, demonstrate interest, and identify crucial evidentiary information.

- Beginning the Interview: Start by clearly stating the reason for the interview, for example, “You are here because you have been arrested for…” or “You are here because you witnessed…”. Verify the interviewee understands the explanation.

- Interview Objectives and Outline: Explain the objectives of the interview and provide a ‘route map’ of topics to be covered. For example, “During this interview, I will discuss…”. Also, indicate that any other relevant issues that emerge will be addressed.

- Routines and Expectations: Explain procedural aspects, such as noting nods or shakes of the head verbally and the practice of note-taking. Emphasize that the interview is an opportunity for the interviewee to explain their involvement or non-involvement and encourage them to voice all relevant information without time constraints or interruptions.

3. Account, Clarification, and Challenge (A, C, C)

This phase focuses on obtaining a detailed account, clarifying ambiguities, and, if necessary, challenging inconsistencies.

- Obtaining an Account: Begin with an open-ended prompt, like “Tell me what happened,” to initiate a free narrative. Support this account through active listening, using non-verbal cues, allowing pauses, and encouraging continuation with minimal verbal prompts like “What happened next?” or reflective questions.

- Clarification and Expansion: Break down the account into manageable topics and systematically probe each using open-ended and specific-closed questions. Ensure all information identified during planning is addressed.

- Question Types: Utilize various question types strategically:

- Open-ended Questions: (e.g., “Tell me,” “Describe,” “Explain”) Ideal for starting interviews, encouraging full accounts, and minimizing interviewer influence.

- Specific-Closed Questions: (e.g., “Who did that?”, “When did this happen?”) Useful for gaining control, eliciting specific details, clarifying points, and challenging accounts.

- Forced-Choice Questions: (e.g., “Was the car an estate or a saloon?”) Can lead to guesswork and should be used cautiously due to potential for inaccuracy or misinterpretation.

- Multiple Questions: (e.g., “Where did he come from, what did he look like, and where did he go?”) Can cause confusion and should be avoided to ensure clear responses.

- Leading Questions: (e.g., “You saw the gun, didn’t you?”) Imply answers and can distort memory or reduce credibility. Use as a last resort.

4. Closure (E)

Plan a structured closure to avoid abrupt endings and ensure all necessary steps are taken.

- Pre-Closure Check: If using two interviewers, the lead interviewer should check with the second interviewer for any final questions.

- Summary and Review: Accurately summarize the interviewee’s account, allowing for clarifications. Address any questions from the interviewee.

- Concluding Actions: Conclude the interview by preparing a witness statement if appropriate, or for suspect interviews, stating the time and date before stopping recording. Explain next steps to the interviewee.

5. Evaluation (E)

Post-interview evaluation is crucial for assessing the information obtained and planning further actions.

- Action Determination: Evaluate the interview to decide if further investigation or action is needed.

- Account Integration: Assess how the interviewee’s account fits into the broader investigation.

- Performance Reflection: Reflect on the interviewer’s performance to identify areas for improvement and learning.

Witness Interview Considerations

Witness interviews, including those with victims, require sensitivity, impartiality, and respect, while maintaining an investigative approach.

- Sensitivity and Support: Treat all witnesses with sensitivity, recognizing they may be in shock or trauma. Offer support and referrals to appropriate agencies with consent.

- Structured Approach: Structure witness interviews to maximize information retrieval, using the PEACE framework.

- Prompt Interviews in Suitable Settings: Conduct interviews as soon as possible after the incident in a quiet, private location to minimize distractions. If immediate interviews are not ideal, arrange for later interviews but obtain a brief recorded and signed account in the interim.

- Witness Statements: Produce statements from witness interviews, taken at the scene or later. Ensure accuracy, retain all notes for potential disclosure, and consider relevant points to prove the offense. For significant witnesses, consider video recording the interview.

- Crime Report Completion: Complete a crime report following victim interviews, in accordance with local policy, as it is a critical document for further investigation and potential evidence.

Structuring Witness Interviews: Free Recall Technique

Utilize free recall to encourage witnesses to recount events in their own terms, enhancing memory recall and accuracy.

- Free Recall Components:

- Ask the witness to describe the events in their own words.

- Adopt active listening, allowing pauses and using minimal prompts.

- Reflect back witness statements appropriately.

- Avoid interruptions.

- Identify and clarify manageable topics within the account.

- Systematically probe topics using open-ended questions initially, then specific-closed questions.

- Avoid topic-hopping and multiple questions.

- Use forced-choice and leading questions only when essential.

- Probe any critical information not adequately covered.

- Contextual Recall: Encourage detailed recall by prompting witnesses to remember contextual elements like feelings, surroundings, weather, and traffic at the time of the incident, which can enhance overall memory recall accuracy.

- Note-Taking: Implement structured note-taking to manage the volume and detail of information effectively, supporting subsequent questioning and clarification.

Suspect Interview Considerations

Suspect interviews require careful management, especially when legal advisors are involved.

Working with Legal Advisors

Investigators must understand the role and objectives of legal advisors, who act in their client’s best interests.

- Legal Advisor Objectives: Legal advisors aim to investigate the police case, protect client rights, explore alternatives to charges, and ensure the most favorable outcome for their client.

- Mutual Respect: Maintain professional respect for the distinct roles of police and legal advisors, despite differing priorities.

- Preparation for Interaction: Plan for all interactions with legal advisors, including pre-interview briefings, suspect interviews, and post-charge processes.

Legal Advisor Roles and Actions:

- Investigate Police Conduct: Scrutinize police actions and evidence.

- Advise Client: Provide best possible legal advice.

- Assess Client Vulnerability: Evaluate the client’s ability to understand and cope with the interview process.

- Determine Safest Responses: Advise on whether to remain silent, provide a statement, or answer questions.

- Influence Police Decisions: Attempt to influence the police not to charge or to consider alternative resolutions.

- Prepare for Charge: Create the best possible position for the client if charges are inevitable.

Legal Advisor Interventions During Interviews:

- Provide Legal Advice: Offer counsel to their client.

- Seek Clarification: Request clearer questions when needed.

- Prevent Oppression: Intervene against oppressive or insulting questioning.

- Object to Suppositions: Prevent questioning based on assumptions.

- Disclosure Objections: Object to questions based on undisclosed material.

- Relevance Objections: Object to questions not relevant to the offense.

- Purpose Objections: Object to questions not aimed at discovering the perpetrator or circumstances of the offense.

Pre-Interview Briefings with Legal Advisors

Pre-interview briefings are crucial meetings between investigators and legal advisors to facilitate informed advice to suspects.

- Purpose: To provide the legal advisor with sufficient information about the investigation to advise their client effectively before the interview, enhancing interview effectiveness and enabling suspects to give accurate accounts.

- Disclosure Strategy: Decide on the extent of disclosure, balancing transparency with the need to protect ongoing inquiries. Partial disclosure may be necessary to avoid prejudicing further investigation.

- Information for Legal Advisors: Provide details on arrest particulars, detention, investigation status, and procedures being considered. Legal advisors need information from custody officers, investigators, and suspects to effectively advise their clients.

- Custody Officer Information: Custody officers should provide information on suspect identity, alleged offense, arrest status, health condition, arresting officers, arrest times, prior interviews, legal advice requests, significant statements, and admissions.

- Preparation for Briefing: Investigators should prepare a structured briefing strategy, outlining what information will be disclosed and when. This includes offense details, arrest circumstances, reasons for interview, and areas to be covered in the interview.

- Disclosure Planning: Plan what information to disclose, considering an outline of the offense, arrest circumstances, suspect history, significant comments at arrest, reasons for interview, and key areas of questioning. Also, consider the briefing location, responses to information requests, staged disclosure, recording disclosures, and management of prepared statements or no-comment interviews.

Managing Removal of Legal Advisors

Removing a legal advisor is an extreme measure, justified only if their conduct obstructs questioning.

- Grounds for Removal: Misconduct includes answering for the client or providing written answers.

- Authorization Required: Removal requires authorization from a superintendent or inspector, who should witness the misconduct and be prepared to justify the decision in court.

Representations by Legal Advisors

Legal advisors may make representations to bring critical matters to the attention of the police, aiming to influence decisions or actions.

- Purpose of Representations: To highlight risks to the defense, legal position, or suspect’s well-being, and to persuade the police to alter actions or decisions.

- Basis of Representations: Representations can be based on facts or law, presenting the suspect’s viewpoint.

- Knowledge Required by Investigators: In-depth PACE and Code of Practice knowledge is crucial to respond effectively to representations.

- Reasons for Representations: These may relate to evidence strength, suspect welfare, necessity of questioning, continued detention, suitability of appropriate adults, identification procedures, searches, sample collection, bail, drug testing, interview monitoring, and video recording.

- Action on Representations: Record all representations and their resolutions in custody records or notebooks, as they may become evidence in legal proceedings.

Structuring the Suspect Interview

Beyond the PEACE model, specific structures and procedures apply to suspect interviews, including downstream monitoring, starting procedures, and managing different interview scenarios.

Interview Structure Stages:

-

Starting the Interview:

- State that the interview is being recorded.

- Introduce interviewer names and ranks.

- Ask the suspect and any other present parties to identify themselves.

- State the date, time, and location.

- Inform the suspect about recording copy procedures.

- Administer the formal caution: “You do not have to say anything. But it may harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned something which you later rely on in Court. Anything you do say may be given in evidence.”

- Remind the suspect of their right to free legal advice.

- Record any significant statements or silences made before the interview.

-

Interviewer’s Objectives:

- Introduce each objective separately.

- Allow adequate response time.

- Probe each objective thoroughly.

- Summarize information verbally after probing each objective.

-

Suspect’s Account:

- Allow the suspect to present their position.

- Define time parameters if relevant.

- Use open questions to encourage narrative accounts.

- Persist with questions if the suspect is evasive.

- Briefly address suspect concerns before redirecting to open questions.

- Avoid interrupting the suspect.

- Take accurate notes for summarization.

- Summarize accounts and identify topics for probing with what, why, where, when, who, how, tell, explain, describe questions.

- Ensure the second interviewer has an opportunity to clarify points.

-

Challenging Accounts:

- Challenge false accounts or inconsistencies without raising voice or using inflammatory language.

- Treat each false account as a separate objective, using probing and summarization techniques.

Voluntary Attendance and Interviews

Voluntary attendance (VA) provides an alternative to arrest for interviewing suspects.

- Voluntary Interview Guidelines:

- Inform volunteers of their right to leave unless arrested.

- Caution volunteers if answers or silence could be used as evidence.

- Advise volunteers of rights equivalent to those under arrest, including free legal advice and the right to information about the offense.

- Assess suspect needs and capabilities, fitness for interview, and need for appropriate adults.

- Record voluntary interviews as per PACE Code E, even using body-worn video outside police custody.

- Obtain documented consent for the interview to proceed.

- Limitations of Voluntary Interviews: Fingerprints and DNA should not be taken during voluntary interviews unless consent is given for photographs, and even then, strict guidelines apply regarding retention and destruction of images.

- Intervention Opportunities: Use voluntary interviews to explore opportunities for risk mitigation, prevention of further offenses, and referrals to support schemes.

Legal Issues in Suspect Interviews

Understanding legal issues is vital, particularly concerning the right to silence, adverse inferences, and bad character evidence.

No Comment Interviews:

- Right to Question: Even during no comment interviews, investigators must ask all planned questions to provide the suspect every opportunity to respond and to create a complete record.

- Preparation is Key: Plan meticulously to address potential no comment scenarios effectively.

Adverse Inferences:

- CJPOA Section 34: Courts can draw adverse inferences from a suspect’s silence or failure to mention facts later relied upon in defense, provided a prima facie case exists.

- Conditions for Adverse Inference: Six conditions must be met, including questioning under caution, failure to mention facts before charge, questions aimed at discovering the offense, failure to mention facts later relied upon, reasonable expectation to mention facts during questioning, and applicability to criminal proceedings.

- Special Warnings: CJPOA Sections 36 and 37 require special warnings before adverse inferences can be drawn from a suspect’s failure to account for objects, marks, or presence at a location.

Bad Character Evidence:

- Criminal Justice Act 2003 (CJA): This act governs the admissibility of bad character evidence, focusing on propensity to commit similar offenses or untruthfulness.

- Relevance of Propensity: Bad character evidence is admissible if it shows propensity to commit offenses of the kind charged or propensity for untruthfulness. Similarities in offense type, victim nature, modus operandi, and language used are relevant.

- Conditions for Admissibility: Specific conditions must be met for bad character evidence to be admissible, and the court must balance probative value against potential unfairness.

- Propensity for Untruthfulness: This is distinct from dishonesty and relates to a defendant’s accounts of their behavior or lies told during an offense.

- Appropriate Conditions for Use: Untruthfulness evidence is relevant if the defendant makes a denial that is disputed. Previous false denials can be presented.

Adverse Inference Package:

- Purpose: To highlight instances during the interview where a suspect had the opportunity to mention facts later used in their defense, supporting the prosecution’s case for adverse inference.

- Preparation: Review defense statements against case documents to identify inconsistencies or new information not previously disclosed during interviews.

- Defence Statement Awareness: Be fully aware of pre-interview briefings, interview plans, custody times, and interview recordings to effectively prepare an adverse inference package.

- Prepared Statements: Suspects may use prepared statements to mitigate adverse inferences. Investigators should still question suspects about the statement’s contents and other relevant matters. Suspend the interview to review prepared statements before proceeding.

Special Warnings: Sections 36 and 37 CJPOA

- Purpose: To alert suspects that failure to account for objects, marks, or presence at a location may lead to adverse inferences.

- Content of Special Warning: Include offense details, specific facts being asked about, reasons for linking facts to the suspect, notice of potential court inferences, and recording of the interview.

- Timing of Special Warning: Introduce special warnings at the end of relevant topics or in the later stages of the interview, before the challenge phase.

- Distinction from Caution: Cautions are given before any questioning; special warnings are additional and specific to adverse inference scenarios under CJPOA sections 36 and 37.

- Section 36 Application: Relates to failure to account for objects or marks found on a suspect at arrest, believed to be linked to the offense.

- Section 37 Application: Relates to failure to account for presence at a place and time of the offense, for which the suspect is arrested.

By adhering to these principles, techniques, and legal frameworks, police investigators can conduct suspect interviews that are not only effective in gathering crucial information but also ethical and legally sound, thereby enhancing the integrity and efficacy of the criminal justice process.