Most people have a general understanding of Heaven and Hell, concepts that are fairly consistent across various Christian denominations. However, Purgatory remains more obscure, largely because it’s primarily a Catholic doctrine, less familiar outside of the Catholic Church. This lack of widespread knowledge leads to numerous misconceptions, from confusing it with Limbo to mistakenly believing it’s a part of Hell. These inaccuracies often find their way into books, movies, and TV shows, perpetuating a cycle of misinformation that can be frustrating for those who understand the true doctrine. To clear up the confusion and provide a helpful guide to the Catholic understanding of the afterlife, especially the often misunderstood concept of Purgatory as your spiritual “ending,” let’s delve into a comprehensive explanation.

Now, many are immediately curious about Heaven and Hell – and if we’re honest, probably more about Hell. There’s a reason Dante’s Inferno is far more widely read than Purgatorio or Paradiso (spoiler alert if you didn’t know Inferno is just the first part of the Divine Comedy). As your guide through this spiritual landscape, it’s essential to clarify who ends up where. This journey begins with understanding the Catholic definition of sin.

Theology offers extensive discussions on the intricacies of sin. For this introductory guide, however, sin can be defined as turning away from God by committing a wrong action, whether it’s murder, adultery, or disrespecting your parents.

While many Christian denominations broadly define sin, Catholicism further categorizes it into two types: mortal and venial. Mortal sins are considered spiritually lethal, meaning they lead to Hell if unforgiven. Venial sins, on the other hand, are less severe and do not warrant eternal damnation. Three factors determine whether a sin is mortal or venial: gravity (severity), knowledge, and willingness.

Severity is subjective, but it essentially distinguishes between a major crime and a minor offense. Murder is significantly more serious than, say, rudely sticking your tongue out at a sibling.

Disclaimer: This example is hypothetical to illustrate severity in sin. The actual gravity of sins depends on context. There could be scenarios where taunting a family member is a mortal sin. The author is not liable for readers facing damnation for sibling-related tongue-sticking incidents.

Even if a sin is not “grave matter” (theological term for Hell-worthy), it might not be mortal if committed without full awareness of its wrongfulness. For instance, if someone genuinely doesn’t understand that killing is wrong due to circumstances beyond their control, then any murders they commit aren’t mortal sins. Similarly, if you know killing is wrong but are unaware your actions will cause death, it’s not a mortal sin (and unlike the first example, this might be a legal defense). However, deliberate ignorance doesn’t count. Blindly firing a gun towards your rich uncle’s mansion is sinful and a severe breach of gun safety.

The final factor is willingness. An unwillingly committed sin cannot be mortal. Examples include coercion (robbing a bank under threat of death), inability to control actions (like lacking legal consent), or impaired capacity (sleepwalking has been a murder defense). Trying to manipulate this factor won’t work. Asking someone to force you to commit a sin doesn’t absolve responsibility. Intentionally placing yourself in a situation to be coerced or impaired, especially to do something normally avoided, still makes you accountable.

In essence, a mortal sin is knowingly and willingly committing a grave evil.

With this context, we can explore the destinations after death. As mentioned, dying in a state of mortal sin leads to Hell – more precisely, dying without repenting for mortal sins. Forgiving sins was central to Jesus’s mission, including mortal sins. Repentance specifics are complex, but Catholics typically seek it through the sacrament of penance (confession). This is also why “last rites,” “extreme unction,” or “anointing of the sick” are crucial for the dying; they offer a final chance for repentance and forgiveness. Sins can also be forgiven through perfect contrition, though it’s riskier. Perfect contrition is genuine sorrow for wrongdoing and a desire to atone, unlike imperfect contrition, which is regret due to fear of consequences, like Hell.

Those who die with unrepented mortal sins go to Hell, separated from God by their own choice. Conversely, those who die free of sin immediately join God in Heaven. But what about everyone else?

This is where Purgatory comes into play, acting as a crucial stage in this psychopomp “ending guide.”

Purgatory, broadly defined, is a state of spiritual purification. If you die with venial sins or still needing to atone for forgiven sins, Purgatory is your initial destination. Crucially, the next stop is Heaven. Purgatory is somewhat like airport security: most must queue, remove shoes, and pass through metal detectors, but TSA PreCheck holders bypass this. Like airport security, Purgatory is generally unpleasant (as facing consequences often is).

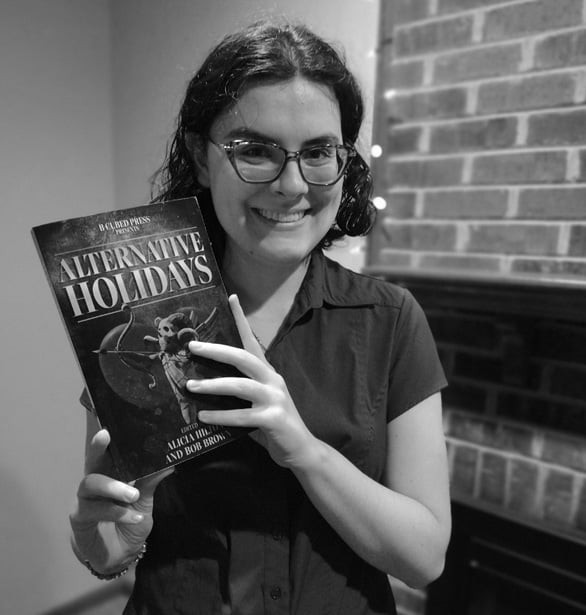

Julia LaFond author

Julia LaFond author

Speaking of pre-checks, this leads to indulgences, a topic familiar to history enthusiasts. Indulgences lessen the divine punishment for already forgiven sins. They are plenary (covering all punishment) or partial (covering some). Plenary indulgences are like skipping Purgatory entirely, while partial ones shorten your stay (assuming no further sins extend it). Indulgences are often linked to devotions, such as the First Saturday devotion, making Penance busy on first Saturdays. Plenary indulgences usually require Eucharist and confession. Confession is technically optional for partial indulgences, but remember, indulgences only affect punishment for forgiven sins.

For those unfamiliar with history, indulgences are significant due to past corruption. Historically, some clergy sold indulgences to wealthy patrons, a sin called simony (selling sacred things). False claims also circulated, such as indulgences guaranteeing Heaven (untrue) or preemptively forgiving future sins (also untrue). This era was during Martin Luther’s time. It’s no coincidence indulgences remain uniquely Catholic.

Back to Purgatory within our “Psychopomp Ending Guide.” It differs from Heaven and Hell by existing within time. Heaven and Hell are eternal, beyond time. In Purgatory, time is meaningful, like on Earth – another similarity to airport security. This is why Catholics pray for the dead: prayers help souls in Purgatory reach Heaven sooner. Catholics also offer up suffering, either as a Lent-like sacrifice or uniting suffering with Christ’s agony on the cross. A Catholic saying, “I’m getting souls out of Purgatory,” indicates personal hardship being offered for these souls.

The question arises: why can’t souls in Purgatory pray themselves into Heaven? Answer: they can’t pray for themselves for that purpose. Some Catholics believe they can’t pray at all in Purgatory, but others think they can pray for the living, like saints in Heaven. Indeed, those in Heaven can easily pray in God’s presence. This is why Catholics ask saints (anyone in Heaven, including Mary) for prayers. God favors these individuals, so their intercession is seen as beneficial. Though called “praying to” saints, it’s not worship, but akin to asking friends or celebrities for prayer, except saints are deceased. (This isn’t necromancy, though the confusion is understandable).

Catholics pray for souls in Purgatory and to saints for intercession. Determining someone’s eternal destination after death is tricky. Without clear evidence, assume Purgatory and pray for them. If they’re in Heaven, prayers are credited back or applied to others, depending on belief (less clear if they are in Hell, but it can’t hurt). Not praying for them, if they are in Purgatory, means neglecting a loved one’s suffering.

Canonized saints are an exception. Early Church canonization was informal, based on martyrdom or public acclaim (everyone agreed they must be in Heaven). It became a lengthy, bureaucratic process. First, a thorough investigation into the candidate’s virtue in life and death. If virtuous, the Pope declares them “venerable”—a “good role model, but not definitely a saint.” Beatification follows, requiring martyrdom or a miracle (waivable by the Pope). Beatification declares them “blessed,” but Heaven isn’t fully certain. Formal canonization, the final step, usually needs a second miracle before the Pope declares them a saint.

Many uncanonized saints exist, honored on All Saints Day, November 1st, for all unknown saints. All Souls Day, November 2nd, honors souls in Purgatory. Yes, it’s after Halloween, and no, it’s not a coincidence. But this is a spiritual guide, not a history lesson; internet searches provide more details.

One last Purgatory aspect, a debated topic: Some Catholics—not official doctrine—believe souls in Purgatory can manifest as ghosts, perhaps as part of their psychopomp “ending journey.” Reasons include atoning for sins, offering warnings, comfort, or guidance, or requesting prayers. Often, all these reasons are intertwined. This interpretation adds a layer to Shakespeare’s Hamlet: though Hamlet’s father mentions Purgatory, his demand for vengeance, not prayers, suggests a less heavenly origin, possibly Hell or demonic masquerade – another Catholic ghost explanation, and why even believers avoid seeking ghosts. The mundane explanation is misidentifying natural phenomena as hauntings, but that’s less interesting. The point is, if you end up in Purgatory, becoming a ghost is a possibility. Something to ponder on a spooky night…

This concludes our “psychopomp ending guide” tour. To recap common Purgatory misconceptions: It’s not part of Hell, nor is it Limbo. Limbo was a temporary place for those pre-Christ, good enough for Heaven but awaiting Christ’s sacrifice. Purgatory isn’t a permanent place for the “in-between”; it’s where souls become good enough for Heaven.

So, if you die and find yourself in Purgatory, don’t despair: Heaven is still your destination.

Eventually…