11:49

New Testament Overviews

Revelation 1-11

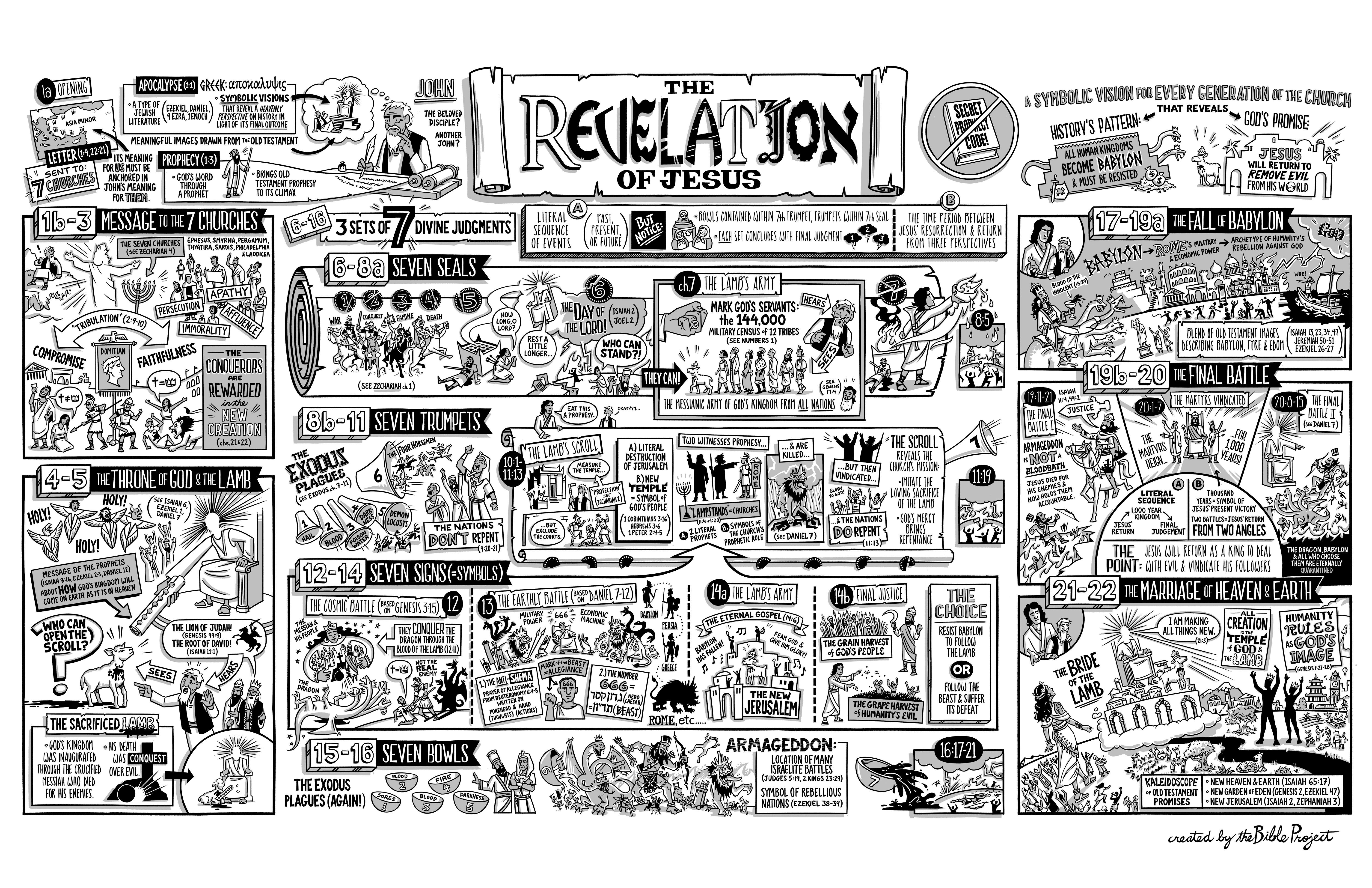

In the introductory words of the Book of Revelation, the author identifies himself as John. This John is widely believed to be the same John who authored the Gospel of John and the letters of John, though some scholars suggest he might be another prominent leader in the early Christian Church. Regardless of his precise identity, John clearly states the nature of this writing: it is a “revelation.” The Greek term used, apokalypsis, gives us the word apocalypse and denotes a specific genre of literature found in both the Hebrew Scriptures and other respected Jewish texts of the time. Apocalyptic writings typically present symbolic visions received by a prophet, revealing God’s celestial perspective on history, allowing the present to be understood in the context of history’s ultimate conclusion. It’s crucial to understand that the symbolic imagery and numerical references within these texts are not designed to obscure meaning but to communicate profound truths in a powerful way. John’s imagery is deeply rooted in the Old Testament, and he expects his readers to engage with and interpret his message by referencing the Old Testament texts he alludes to, enriching their understanding of this complex book.

Authorship of the Book of Revelation: Who Wrote Revelation?

While Christian tradition overwhelmingly attributes the Book of Revelation, often titled “The Revelation of Jesus Christ to John,” to the Apostle John, the text itself does not explicitly confirm his identity. Internal clues and early church testimonies strongly suggest the apostle as the author.

Historical Context of Revelation

The events depicted in Revelation are specifically directed towards seven church communities located in Asia Minor, a region now part of modern-day Turkey. Scholarly consensus places the composition of Revelation between 94 and 96 C.E., during the reign of the Roman Emperor Domitian. This period was marked by increasing pressure on Christians, potentially including persecution, which forms a significant backdrop to the book’s message.

Key Themes in Revelation

- The Sure Hope of Jesus’s Return: Revelation is imbued with the unwavering expectation of Jesus Christ’s triumphant return, offering hope amidst present trials.

- Living Faithfully to Jesus: The book emphasizes the importance of steadfast loyalty and devotion to Jesus throughout all aspects of life, even in the face of adversity.

- Comfort and Strength in Suffering: Revelation provides solace and encouragement to believers experiencing suffering and persecution, assuring them of Jesus’s presence and ultimate victory.

Structure of Revelation

The Book of Revelation unfolds in a structured series of visions, broadly divisible into seven parts:

- Chapters 1-3: Introduce John’s initial vision of the glorified Christ and messages to the seven churches.

- Chapters 4-5: Present a vision of God’s heavenly throne room and the Lamb worthy to open the scroll.

- Chapters 6-8a: Detail the opening of the first six seals of the scroll, unleashing judgments upon the earth.

- Chapters 8b-11: Describe the seven trumpet judgments, escalating the divine warnings.

- Chapters 12-16: Shift focus to symbolic visions of cosmic conflict, including the dragon and the beasts.

- Chapters 17-20: Depict the fall of Babylon, the defeat of Satan, and the millennial reign of Christ.

- Chapters 21-22: Conclude with the glorious vision of the new heaven and new earth, and the eternal state.

Revelation 1-3: Jesus Speaks to the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

John identifies the Book of Revelation not just as a revelation, but specifically as a prophecy. In its essence, prophecy is understood as a word from God, delivered through a prophet, intended to either comfort or challenge God’s people. This particular apocalyptic prophecy was directly addressed to real communities of faith known to John. The book adopts the format of a circular letter, a common method of communication in the ancient world, designed to be circulated among seven specific churches located in the Roman province of Asia. The letter format of Revelation underscores that John was directly communicating with these first-century congregations. While Revelation holds profound meaning for Christians across all eras, its interpretation must begin by grounding it within the historical and geographical context of John’s time and the specific circumstances of these early churches.

John recounts his exile on the island of Patmos, where he experienced a powerful vision of the resurrected Jesus standing amidst seven lampstands ablaze with light. This imagery, drawing from Zechariah 4, symbolizes the seven distinct churches in Asia Minor. Jesus, in the vision, directly addresses the unique challenges and strengths of each church. Some congregations were marked by spiritual apathy, possibly stemming from their material wealth and comfort, while others had compromised their moral integrity. Yet, within these churches, there were also those who remained steadfastly faithful to Jesus, enduring harassment and even persecution. Jesus issued a warning about an impending “tribulation” that would confront these churches, forcing them to choose between compromising their faith or remaining faithful.

By the time John wrote Revelation, the brutal persecution of Christians under Emperor Nero was past, but the pressures, possibly including persecution, under Emperor Domitian were likely growing. Jesus’s message to these churches is a call to unwavering faithfulness. He promises that those who remain faithful will “conquer” and inherit a reward in the ultimate union of Heaven and Earth. This opening section of Revelation establishes the central tension that runs throughout the entire book: Will Jesus’s followers remain faithful and inherit the promised new world God has prepared? And importantly, why is this faithfulness to Jesus described as “conquering”? This sets the stage for exploring the nature of victory in God’s kingdom.

Revelation 4-5: The Heavenly Throne Room and the Lamb

John’s vision next transports him to God’s heavenly throne room, a scene richly described with imagery echoing numerous Old Testament prophetic books. Surrounding God are celestial beings and elders, representing the entirety of creation and the nations of humanity, all united in offering honor and allegiance to the one true God. In God’s hand, John sees a scroll sealed with seven wax seals, reminiscent of the prophetic scrolls of the Old Testament and Daniel’s visions. These scrolls symbolized messages about the establishment of God’s Kingdom on Earth, mirroring its perfection in Heaven.

However, a critical question arises: who is worthy to open this pivotal scroll and unleash God’s kingdom purposes? Initially, no one is found to be qualified, causing John great distress. But then, he learns of one who is worthy: “the Lion of the tribe of Judah” and “the Root of David” (references to Genesis 49:9 and Isaiah 11:1). These titles are classic Old Testament descriptions of the expected Messiah-King, who was prophesied to usher in God’s Kingdom through a powerful, even military, victory. This is the expectation John hears. Yet, what he sees is profoundly different: not a conquering lion-king, but a Lamb, appearing as if sacrificed, bearing the marks of bloodshed, yet now alive and standing, ready to open the scroll.

This symbolic representation of Jesus as the slain Lamb is absolutely central to grasping the message of Revelation. John is declaring that the Old Testament promise of God’s future Kingdom was inaugurated, launched, through the crucified Messiah. Jesus, in his sacrificial death, became the true Passover lamb, offering redemption for his enemies and for all who would believe. His death on the cross was, paradoxically, his enthronement, his moment of “conquering” evil not through force, but through self-giving love. The vision culminates with the Lamb standing alongside God on the throne, both receiving worship as the one true Creator and Redeemer. With divine authority now vested in the Lamb, he begins to break the seals of the scroll, signifying his power to guide history towards its divinely ordained conclusion.

This pivotal scene in heaven leads directly into the next major section of Revelation, characterized by three cycles of seven: seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven bowls (or plagues). Each cycle depicts the arrival of God’s Kingdom and justice on Earth, reflecting the perfect order of Heaven. Interpretations of these cycles vary. Some understand them as a literal, chronological sequence of events, unfolding either in the past, present, or future, particularly leading up to Jesus’s second coming. However, it’s crucial to note John’s literary weaving of these cycles. The seven bowls emerge from the seventh trumpet, and the seven trumpets themselves emerge from the seventh seal. They are structured like nested containers, each “seventh” element encompassing the next set of seven. Furthermore, each series culminates in a similar depiction of final judgment. This intricate structure suggests that John is likely employing each set of seven to present three distinct perspectives on the same period of time following Jesus’s resurrection and ascension. These are not necessarily linearly sequential events, but rather different facets of God’s unfolding plan and judgment throughout history.

Revelation 6-8a: The Cry of the Martyrs and the Sealing of God’s People

As the Lamb begins to open the first four seals of the scroll, John witnesses the emergence of four symbolic horsemen, an image borrowed from Zechariah 1. These horsemen represent periods of war, conquest, famine, and death – the harsh realities of human history. The opening of the fifth seal reveals a poignant scene: the martyred Christians gathered before God’s heavenly throne. Their innocent blood cries out to God for justice, and they are told to rest, for tragically, more believers are destined to suffer martyrdom. The sixth seal then brings God’s ultimate response to their cry – the arrival of the great Day of the Lord, a concept vividly described in Isaiah 2 and Joel 2. This day is marked by cosmic upheaval and divine judgment, causing the people of the earth to cry out in terror, “Who is able to stand?”

At this critical juncture, John pauses the unfolding action to answer this very question: Who can withstand the Day of the Lord? He sees an angel, bearing a signet ring, sent to place a protective mark on God’s servants who are enduring these trials. John then hears the number of those sealed: 144,000. This number is derived from a military census, twelve thousand from each of the twelve tribes of Israel (as in Numbers 1). It’s important to note that John hears the number, just as he heard about the conquering Lion of Judah earlier. In both instances, what John turns to see is a surprising fulfillment through Jesus, the slain Lamb. The 144,000 represent the messianic army of God’s Kingdom. Crucially, this army is not limited to ethnic Israel, but is composed of people from every nation and tribe, fulfilling God’s ancient promise to Abraham to bless all nations. This multi-ethnic army of the Lamb is able to stand before God not because of their own merit, but because they have been redeemed by the Lamb’s blood. They are called to conquer, not through military might, but by mirroring the Lamb’s sacrifice, enduring suffering and faithfully bearing witness to the gospel. With this vision of God’s sealed people, the seventh and final seal is broken. But before the scroll is fully opened, the seven warning trumpets emerge, signaling a further unfolding of God’s judgment and paving the way for the ultimate Day of the Lord to bring final justice.

Revelation 8b-11: Trumpets, the Temple, and the Two Witnesses

As we transition to the cycle of seven trumpets, John revisits the themes of judgment, drawing this time from the narrative of the Exodus. The first five trumpet blasts echo the plagues that were inflicted upon Egypt, demonstrating God’s judgment against oppression and idolatry. The sixth trumpet unleashes the four horsemen previously seen in the seal judgments, suggesting an intensification of the trials and tribulations upon the earth. However, John pointedly notes that despite these severe plagues, “the nations did not repent,” mirroring the stubborn refusal of Pharaoh in the Exodus story. This highlights a crucial truth: divine judgment alone does not automatically lead people to repentance and humility before God.

Again, John pauses the action. An angel appears, bringing John the unsealed scroll that was initially opened by the Lamb. John is commanded to eat the scroll and then proclaim its message to the nations. This act symbolizes John internalizing and becoming a messenger of the scroll’s contents. Finally, with the Lamb’s scroll now fully opened and proclaimed, we begin to understand more deeply how God’s Kingdom will ultimately be established.

The scroll’s message is revealed through two key symbolic visions. First, John sees God’s temple and the faithful within it, and he is instructed to measure and set it apart, an image of divine protection drawn from Zechariah 2:1-5. However, the outer courts and the city are excluded and given over to be trampled by the nations. Some interpretations take this as a literal prophecy of the destruction of Jerusalem, either in the past or future. However, in light of the New Testament’s use of temple imagery, it’s more likely that John is using the temple as a symbolic representation of God’s new covenant people, the Church, just as other apostles did (see 1 Corinthians 3:16, Hebrews 3:6, 1 Peter 2:4-5). This vision suggests that while Jesus’s followers may face persecution and external defeats in the world, these cannot negate their ultimate victory secured through the Lamb.

This concept of victory through apparent defeat is further developed in the scroll’s second vision: the two witnesses. God appoints two witnesses to act as prophetic representatives to the nations. Some understand these literally as two individual prophets who will appear in a future time. However, John explicitly identifies these figures as “lampstands,” a symbol he has already clarified as representing the churches themselves (Revelation 1:20). This strongly suggests that the vision is about the prophetic role of Jesus’s followers, who, like Moses and Elijah, are called to challenge idolatrous nations and rulers, urging them to turn to God. A terrifying beast then emerges, who overcomes and kills the witnesses (echoing the beast imagery of Daniel 7). But in a dramatic reversal, God raises the witnesses back to life and vindicates them before their persecutors. This powerful display of divine power and faithfulness leads to repentance and a turning to the Creator God among many within the nations.

Let’s pause and reflect on the narrative so far. The warning judgments of the seals and trumpets, while severe, did not bring about widespread repentance among the nations. Now, the Lamb’s opened scroll reveals a surprising and counter-intuitive mission for his army – the Church. God’s Kingdom is advanced not through military conquest, but when the nations witness the Church mirroring the Lamb’s sacrificial love, loving their enemies instead of retaliating. It is God’s mercy, demonstrated through the faithful witness of the Church, that will ultimately move the nations towards repentance. Following this witness and the response it evokes, the seventh trumpet sounds, and the nations are shaken as God’s Kingdom begins to be fully realized on Earth, mirroring its perfection in Heaven.

The message of the scroll is now revealed, but a crucial question remains: Who is this terrible beast who wages war against God’s people? John addresses this question in the second half of the Book of Revelation.

Revelation 12-16: The Dragon, the Beasts, and the Mark

Having unveiled the surprising message of the Lamb’s opened scroll, John now presents a series of seven symbolic visions, which he terms “signs” (Revelation 12-15). The term “sign” indicates that these are not literal depictions but symbolic representations. These chapters delve deeper into and expand upon the core message of the Lamb’s scroll, providing further insight into the spiritual realities at play.

The first “sign” reveals the cosmic, spiritual battle that underlies the Roman Empire’s persecution of Christians, tracing this conflict back to its origins in Genesis 3:15. The serpent of the Garden of Eden, the source of all spiritual evil, is now depicted as a powerful dragon. This dragon attacks a woman and her offspring, who represent the Messiah and his people. However, the Messiah triumphs over the dragon through his death and resurrection, casting the dragon down to Earth. Though confined to Earth, the dragon continues to inspire hatred and persecution against the Messiah’s followers. Yet, God’s people are assured that they will “conquer” the dragon, not through worldly power, but by resisting his spiritual influence, even if it leads to physical death. John is revealing to the seven churches that their true enemy is not Rome or any earthly power, but underlying spiritual forces of darkness. Victory is achieved through faithfulness and love for enemies, not through worldly combat.

John’s subsequent vision revisits this same cosmic conflict, now employing the symbolism of Daniel’s animal visions (Daniel 7-12). John sees two beasts emerge. The first beast symbolizes national military power, which conquers through violence and coercion. The second beast represents the deceptive power of economic and ideological propaganda, which elevates this worldly power to a divine status and demands absolute allegiance from all. This demand for total allegiance is symbolized by taking the “mark of the beast” and his number, 666, on the forehead or hand.

The meaning of this “mark” is illuminated by the Old Testament context, specifically the “Shema.” The Shema is a foundational Jewish prayer of allegiance to God found in Deuteronomy 6:4-8. It commanded Israelites to bind God’s law on their foreheads and hands as a symbol of dedicating all their thoughts and actions to the one true God. The mark of the beast is presented as an “anti-Shema,” a forced allegiance to worldly power instead of to God.

The number of the beast, 666, is also symbolic. John, fluent in both Hebrew and Greek, and writing to an audience familiar with these languages, likely intended his readers to recognize that in Hebrew gematria (where letters also represent numbers), spelling out “Nero Caesar” or “beast” in Hebrew both numerically equate to 666. John is not necessarily stating that Nero was the sole fulfillment of this vision, but rather that Nero serves as a recent and potent example of a recurring pattern explored in the book of Daniel. Human rulers and empires become “beastly” when they claim divine authority for their power and economic systems, demanding absolute loyalty and worship. Babylon was the beast in Daniel’s time, followed by Persia, then Greece, and now Rome in John’s day. This pattern, however, is not limited to these historical empires; it represents a recurring temptation for any nation or power structure that seeks to usurp God’s rightful place.

Standing in stark contrast to the dragon’s beastly nations is another king: the slain Lamb, and his army, comprised of those who have willingly given their lives to follow him. From the heavenly New Jerusalem, their song, the “eternal Gospel” (Revelation 14:6), goes out to the nations. All people are called to repent, worship the true God, and “come out of Babylon,” rejecting allegiance to the beastly powers. John then sees a vision of final judgment, symbolized by two harvests. The first is a harvest of good grain, where King Jesus gathers his faithful people. The second is a harvest of wine grapes, representing humanity’s intoxication with evil, which are gathered and trampled in a winepress, signifying divine judgment. Through these powerful “sign” visions, John presents the seven churches with a critical choice: Will they resist the allure of Babylon and faithfully follow the Lamb, or will they succumb to the beast and ultimately share in its defeat?

John then presents a final cycle of seven divine judgments, symbolized as seven bowls (or vials) of wrath. Resembling the plagues of the Exodus, these bowl judgments, however, do not lead to repentance. Instead, they provoke defiance and blasphemy – people curse God, just as Pharaoh hardened his heart. With the sixth bowl, the dragon and the beasts gather the nations together for battle against God’s people at a place called Armageddon. Armageddon, referring to the plain of Megiddo in northern Israel, a site of numerous historical battles (Judges 5:19, 2 Kings 23:29). Interpretations of Armageddon vary. Some see it as a literal future battle, while others understand it symbolically as representing the final confrontation between good and evil. Regardless of the literal or symbolic interpretation, John draws upon the imagery of Ezekiel 38-39, where God battles Gog, representing the rebellious forces of humanity. Thus, in the seventh bowl, evil is decisively defeated among the nations, paving the way for God’s ultimate reign.

Revelation 17-20: The Fall of Babylon and the Final Victory

Having fully unpacked the message of the Lamb’s unsealed scroll and revealed the spiritual conflict behind worldly powers, John now expands on three key themes previously introduced: the fall of Babylon, the final battle against evil, and the arrival of the New Jerusalem. Each of these themes offers a different perspective on the ultimate coming of God’s Kingdom.

John is shown a vision of a striking woman, adorned as a queen, yet shockingly drunk with the blood of martyrs and innocent people. She is seated upon the dragon from the earlier “sign” visions and is identified as “Babylon the prostitute.” For John’s first readers, the detailed symbols of this vision would have been readily understood as representing the military and economic might of the Roman Empire. However, the vision’s significance extends beyond Rome alone. John intentionally weaves together language and imagery from numerous Old Testament prophecies concerning the downfall of Babylon, Tyre, and Edom (Isaiah 13, 23, 34, 47, Jeremiah 50-51, Ezekiel 26-27). He is demonstrating that Rome is simply the latest manifestation of an ancient archetype: humanity in rebellion against God. Nations that elevate their own economic and military security to a position of divine importance, demanding ultimate allegiance, are not limited to the past or future. “Babylons” will continue to arise and fall throughout history, until Jesus returns to replace them all with his eternal Kingdom.

Throughout Revelation, the Day of the Lord has been portrayed in various ways – as a day of fire, earthquake, or harvest. Here, at the book’s climax, it is depicted as a final battle (Revelation 19:11-21, 20:7-15) that results in the vindication of the martyrs (Revelation 20:1-6). John returns to the scene of the sixth bowl, where the nations are gathered to oppose God. Jesus now appears as the ultimate hero, riding a white horse, prepared to “conquer” the world’s evil. Yet, significantly, John notes that Jesus is covered in blood before the battle even begins (Revelation 19:13). This is his own blood, shed in sacrifice. And his sole weapon is “the sword of his mouth,” an image drawn from Isaiah 11:4 and 49:2.

John is emphasizing that Armageddon is not a literal bloodbath of earthly warfare. The same Jesus who willingly shed his blood for his enemies now comes proclaiming justice, holding accountable those who have refused to repent of the devastation they have inflicted on God’s good world. The destructive hellfire that they have unleashed upon the world justly becomes their divinely appointed destiny – separation from God’s life-giving presence.

Following this judgment scene, John sees a vision of Jesus’s followers who were martyred by Babylon. They are brought to life to reign with the Messiah for a thousand years. After this period, the dragon once again rallies the nations of the world for a final rebellion against God. However, they are all brought before God’s throne of judgment and face the ultimate consequence of eternal defeat. The forces of spiritual evil, and all who choose to align with them and reject God’s Kingdom, are finally destroyed. They are given what they ultimately desire: to exist apart from God, solely for themselves. The dragon, Babylon, and all who choose them are eternally quarantined, rendered incapable of ever again corrupting God’s new creation.

There is ongoing debate regarding the interpretation of the thousand-year period that is placed between these two battle scenes. Some understand it as a literal, chronological sequence: Jesus’s physical return, followed by a thousand-year earthly reign, and then the final judgment. Others interpret the thousand years symbolically, representing the present victory of Jesus and the martyrs over spiritual evil, while the two battles depict Jesus’s future return from two complementary perspectives. Regardless of the specific interpretation, the central message is clear: John promises the certain return of King Jesus to decisively deal with evil forever and to fully vindicate those who have remained faithful to him.

The book concludes with a glorious vision of the marriage of Heaven and Earth (Revelation 21:1-22:9). An angel reveals to John a radiant bride, symbolizing the new creation that eternally unites God and his covenant people in perfect harmony. God himself declares that he has come to dwell with humanity forever, making all things new (Revelation 21:5).

Revelation 21-22: The New Heaven and New Earth

This concluding vision is a breathtaking tapestry woven from Old Testament promises. It portrays a new Heaven and Earth (Isaiah 65:17), a restored creation healed from the pain and evil of human history. It is a return to a perfected Garden of Eden (Genesis 2), a paradise of eternal life in God’s presence. Yet, it is not merely a return to the garden; it is a step forward into the magnificent New Jerusalem (Isaiah 2). This is a grand city where human cultures, in all their beautiful diversity, flourish together in peace and harmony. In a surprising and profound twist, there is no temple in this new creation. The very presence of God and the Lamb, once localized in the temple, now permeates every aspect of this renewed world. This is the fulfillment of humanity’s original calling, given on the first page of the Bible (Genesis 1:26-28): to reign as God’s image-bearers, partnering with God in taking his creation into new, unimaginable realms of flourishing.

Thus concludes both John’s apocalypse and the epic narrative of the Bible. John did not write Revelation as a secret code to decipher the precise timeline of Jesus’s return. Rather, it is a powerfully symbolic vision intended to bring both challenge and enduring hope to the seven first-century churches and to every generation of believers since. Revelation unveils the recurring patterns of history and the unwavering promise of God, demonstrating how every human kingdom, in its fallen state, eventually tends towards becoming “Babylon,” and must be resisted by faithful followers of the Lamb. But the Messiah, Jesus, who demonstrated ultimate love by dying for the world, will not allow Babylon to continue unchecked. He will return in glory to eradicate evil from his good creation and make all things new. This certain promise should inspire unwavering faithfulness in every generation of God’s people until the King finally returns to establish his eternal kingdom.