Abstract

To enhance communication strategies aimed at promoting sexual health equity in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) investigated African Americans’ perceptions of the sexually transmitted disease (STD) issue within their communities. The study also explored their reactions to STD data that highlighted racial disparities and their opinions regarding the dissemination of such information. Semi-structured group discussions and individual interviews were conducted with 158 African-American adults across the Southeastern and Midwestern regions of the United States. The majority of participants recognized STDs as a problem in their communities but were not fully aware of the disproportionate impact on African Americans. Upon learning about racial disparities in STD rates, common reactions included shock, fear, and despair, while a few questioned the data’s origin and reliability. Most participants emphasized the importance of sharing this information within African-American communities as a crucial ‘wake-up call’ to encourage change, although some expressed concerns about how it should be communicated. The findings suggest that information about racial disparities in STD rates needs to be carefully crafted and delivered through appropriate channels to resonate positively with African-American audiences. To avoid further disadvantaging communities already facing social and health inequities, alternative, strength-based approaches should be considered to motivate positive change.

Introduction

In the United States, African Americans experience a significantly higher burden of reported sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) compared to any other racial group, including Whites, Hispanics, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and American Indians/Alaska Natives [1]. Despite representing less than 13% of the U.S. population [4], African Americans account for almost half of all reported cases of HIV, chlamydia, and syphilis [2, 3] and 70% of gonorrhea cases [2]. These racial disparities in STD rates vary depending on age, sex, and geographic location [2, 3]. While behavioral factors like age at sexual initiation, number of sexual partners, and concurrent relationships contribute to these differences [5–8], the disparities persist even after accounting for individual risk behaviors [9]. Furthermore, STD rates are influenced by a complex web of social and structural determinants, including poverty, education, health literacy, stigma, gender imbalances, and incarceration rates. These factors can limit access to adequate STD/HIV testing, treatment, and care, influence sexual networks by potentially exposing lower-risk individuals to higher-risk partners, and restrict the ability to make safer sexual choices or negotiate safe sex practices [10–12]. High STD prevalence within communities and sexual network patterns can place African Americans at greater risk, even when their sexual behaviors are considered normative [13, 14], meaning individuals traditionally seen as ‘low risk’ could face a higher risk of STDs, including HIV.

Addressing these complex disparities requires multi-faceted interventions at the individual, community, and policy levels to promote sexual health [10, 15]. Experts have advocated for media campaigns to inform sexually active African Americans about the high prevalence of STDs across various behavioral groups, reduce STD-related stigma, and encourage prevention and testing [9]. Many argue that raising awareness of ‘health disparities’ is a crucial initial step to encourage individual behavior change and mobilize communities to advocate for necessary policy and program adjustments [16–23]. The Department of Health and Human Services [19], in its ‘National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity’, recommends employing best practices in marketing and communication to develop strategies that raise awareness of health disparities and promote actions to eliminate them, particularly among affected racial and ethnic groups.

However, communicating about health disparities can be challenging, especially within vulnerable populations that may have limited health literacy or numeracy skills, and when dealing with stigmatizing health issues like STDs [17, 24]. Some experts have expressed concern about disseminating racially comparative STD data, arguing it could increase public blame towards those most affected and foster feelings of hopelessness, powerlessness, and distress within vulnerable communities [17, 25–31]. A recent study by Nicholson et al. [32] on messaging effects on African-American intentions to screen for colon cancer found that using racially comparative data (‘disparity messaging’) led to negative reactions and decreased the desire for screening. The researchers concluded that such messaging ‘may undermine prevention and control efforts among African Americans’ (p. 2951).

These findings raise significant concerns about using disparity messaging to promote sexual health equity, particularly if efforts begin by educating vulnerable populations about STD disparities. HIV has become the most prominent health disparity issue covered in news media [33], and over half (54%) of African Americans are now aware of HIV/AIDS disparities between African Americans and Whites [16]. Yet, the individual and community responses to this increased awareness remain largely unexamined. There is a lack of research on awareness of racial disparities for other, more common but less fatal STDs, and little is known about how African Americans perceive or react to racially comparative information regarding STD rates.

This study aimed to address these research gaps by exploring the perceptions of sexually active African Americans regarding the STD burden in their communities, their reactions to racially comparative STD data, and their opinions on disseminating such information. This was achieved through individual and small-group discussions in four communities with high STD incidence. This exploratory research, guided by a health communication framework [34], sought to gain a deeper understanding of the target audience’s STD-related knowledge, perceptions, and beliefs, and to explore potential communication strategies for tackling the issue in affected communities. It formed part of a larger study designed to inform the development of a communication initiative to promote sexual health equity in the United States.

Methods

The study involved 32 triad group discussions and 64 individual interviews with sexually active, heterosexual African-American adults aged 18–45 years. Participants were recruited from two urban and two rural communities with high STD incidence in the Southeastern and Midwestern United States. High-incidence communities were selected based on an analysis of gonorrhea case data from the CDC’s National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System; STD rates in these communities ranged from 238.3 to 678.2 per 100,000 residents [35]. These regions were chosen because the South has the highest number of reported STD/HIV cases among African Americans, while the Midwest and Northeast report STD rates for African Americans that are as high or even higher [36].

Recruitment was quota-based and commenced four weeks prior to the scheduled interviews. Urban participants were recruited via phone through professional recruitment firms. Initial recruitment in rural areas utilized online and print advertisements through community-based organizations. However, recruiting in rural areas, particularly individuals with a high-school education or less, proved challenging. Consequently, efforts were supplemented with street outreach, snowball sampling, and outbound calls by professional recruitment firms. Eligibility criteria included being English-speaking, self-identifying as African American, heterosexual, aged 18–45, and sexually active within the past 6 months. Individuals who did not meet these criteria, had participated in health research in the previous 6 months, or worked in marketing/advertising/health (or had immediate family members in these fields) were excluded. Participants were assigned to triads or individual interviews based on their availability.

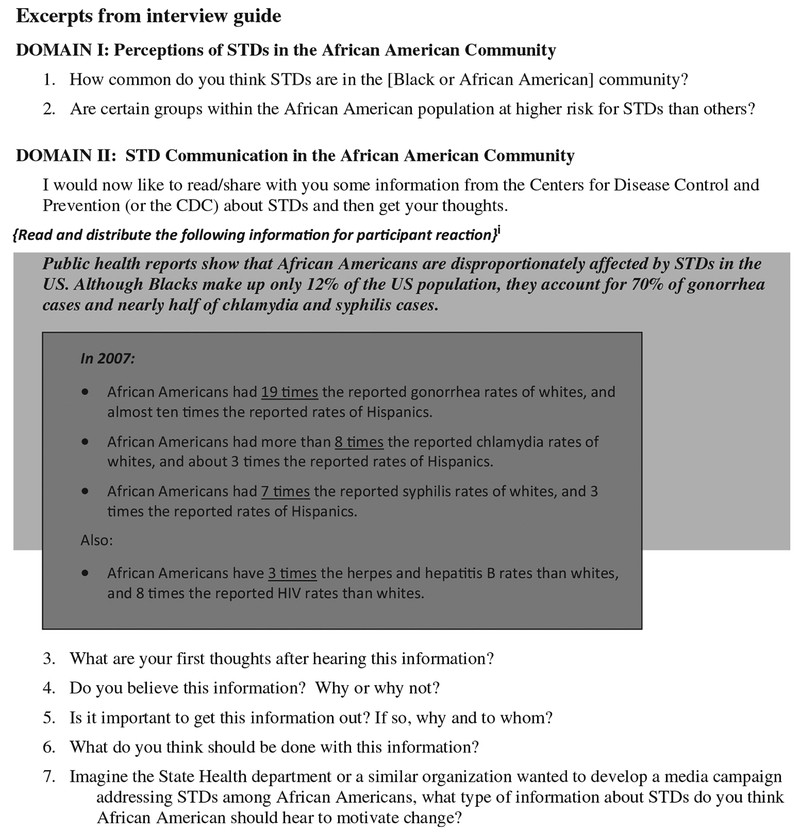

Triads were segmented by age (18–29 years, 30–45 years) and gender. Discussions lasted 1.5 hours for triads and 1 hour for individual interviews. They were conducted in market research facilities for urban sites and at community-based organizations for rural sites. A semi-structured discussion guide, developed using a health communication framework [34], explored two key areas: (i) perceptions of the STD burden on African-American communities and (ii) STD communication issues, including reactions to racially comparative STD data and suggestions for motivating change within African-American communities through a hypothetical campaign. Figure 1 highlights specific research questions from the interview guide. These areas were part of a broader set of research domains in the larger exploratory study. The guide was pilot-tested with eight participants and revised for clarity and comprehension prior to the study.

Fig. 1.

Click on image to zoom

Research questions and CDC information presented to participants

Note: Data from 2007 was the most current available at the time of research.

Each triad and interview was conducted by a trained interviewer, matched to the participant’s race and sex, and experienced in ethnographic research methods to elicit detailed and insightful responses. Interviewers allowed discussions to progress naturally, adjusting the order and time spent on each question based on participant responses. Consequently, not every question was covered in each interview or triad. Plain-language information from the CDC, comparing reported STD rates among African American, White, and Hispanic populations in the United States (Figure 1), was provided to participants in hard copy and read aloud by interviewers before discussing reactions. All discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed, and observed by at least one note-taker and project staff member. At the conclusion of each discussion, participants received plain-language STD information from the CDC and compensation for their time.

The analysis was guided by two theoretical approaches: grounded theory [37, 38], which involves identifying themes, categories, and terms used by participants, and schema analysis [39, 40], which focuses on identifying metaphors and symbols used to convey ideas and concepts. Schema analysis, methodologically similar to grounded theory, views talk as a way to understand how people interpret and reason about experiences, particularly the shared aspects of cognition. In schema analysis, the focus is often on the metaphors and symbols people use to share ideas and concepts.

A team of three analysts coded the transcripts using QSR’s NVivo8 software, applying codes developed from a review of notes and identified themes corresponding to the interview guide questions. For some questions, the range of participant responses was narrowly defined by the question’s nature (e.g., ‘How common do you think STDs are in the African American community? Do you believe the provided STD information?’), allowing for separate coding and analysis of responses to individual questions. However, for more open-ended questions (e.g., ‘What do you think should be done with this information?’), a more inductive approach was used, with general codes applied to responses across the dataset.

Two interviews and one triad were initially coded by all three analysts. They then compared coding, resolved discrepancies, and continued coding the remaining interviews. The code list was further refined as needed. During data analysis, analysts also searched for patterns in responses based on demographic segments such as age, gender, urban/rural location, and education level.

The research received ethical approval from the CDC and RTI Institutional Review Boards. Safeguards were implemented to protect participant rights throughout the research process. Personal participant information was only collected during screening and was not shared with RTI/CDC staff or other participants, being destroyed after study completion. Participants were informed of their rights and provided informed consent before triad/interview sessions. Only first names were used as identifiers in recordings. Audiotapes were destroyed at the study’s end.

Results

The sample consisted of 158 participants, evenly distributed by gender, age (18–29 years, 30–45 years), and education level [high-school diploma or less (HS)] (Table 1). The majority (79.8%) were single. Almost half (47%) reported full-time employment and household incomes below $20,000. Most had health insurance (65%) and had been tested for STDs at least once (85%). Approximately 30% reported a history of incarceration.

Table I.

Participant characteristics

| N (%) |

|---|

| Gender |

| Male |

| Female |

| Age (mean = 31) |

| 18–29 years old |

| 30–45 years old |

| Marital status |

| Single |

| Married |

| Divorced/widowed |

| Ever been tested for a STD |

| Yes |

| No |

| Last STD test |

| <6 months ago |

| 7–11 months ago |

| 1–2 years ago |

| 3–5 years ago |

| >5 years ago |

| Primary care doctor |

| Yes |

| No |

| Health insurance |

| Yes |

| No |

| Household income |

| <$20000 |

| $20000–$39999 |

| $40000–$59999 |

| >$60000 |

| Education |

| High-school diploma, GED or less |

| Some college/technical, not graduate |

| College graduate or higher |

| Current employment situation |

| Working full time |

| Working part time |

| Unemployed or laid off |

| Full time/part time student |

| Not able to work because of disability/illness |

| Ever been in jail or prison |

| Yes |

| No |

Open in a new tab

Results are presented below based on key research questions. Unless specifically mentioned, no significant differences were observed across gender, age, urban/rural location, or education segments.

Perceptions of STDs in African-American communities

How common are STDs believed to be in the African-American community?

Most participants believed STDs were prevalent, citing news reports (television) and classroom discussions (among younger participants) about higher STD/HIV rates among African Americans. They often used ‘STDs’ and ‘HIV’ interchangeably, frequently referring to HIV when discussing this information. Some participants expressed sentiments like ‘black people have all the problems’ or ‘are highest in everything’. Men were more inclined to argue against generalizations, noting the heterogeneity of the African-American population, and suggesting socioeconomic status as a more significant factor in STD rates than race.

I think they are really common because a lot of minors in the Black community are sexually active and they are not really educated on how you can become infected or what precautions it takes to protect yourself … That is, blacks in general and minors are sexually active, and blacks in general aren’t educated.—Female, 18–29 years, Urban, ≤HS

How common? … it depends on what section of the black community you’re talking about. People always look at us as … as a monolithic people. We’re different, so [laughter] it depends on what section of the black community you’re talking about … it may not be as common [in higher income neighborhoods], maybe because of some things there like socialism or classism.—Male, 30–45 years, Urban, >HS

Are certain groups within the African-American population considered at higher risk for STDs?

Participants frequently identified youth, particularly dropouts and those with limited parental supervision, as well as low-income and uneducated individuals, as being at higher risk for STDs. Youth were often perceived as ‘promiscuous’, lacking sexual health education and knowledge of preventative measures, focused on immediate gratification, and lacking access to healthcare. Other high-risk groups mentioned included gay/bisexual men (in one urban setting) and individuals engaging in sex work, drug use, and having multiple partners.

These young girls be sleeping with old men trying to get some change. Trying to get a little money.—Female, 18–29 years, Rural, >HS

I think the younger generation and the poverty community because they have no direction, a lot of them, have no plan. They’re raising themselves… Because they, they not getting the guidance that’s needed to make them go in a positive direction about it. And drugs.—Male, 30–45 years, Urban, >HS

Homosexual men having sex. Down low. Yeah, they down-low people … brothers and going home sleeping with their woman—Female, 18–29 years, Rural, >HS

Reactions to racially comparative STD data

What were the initial reactions upon hearing the STD disparity information?

Participants commonly expressed initial reactions of sadness, surprise, fear, and despair. Many questioned why African Americans consistently bear the heaviest burden of diseases.

That is really scary if we have more than everybody.—Female, 18–29 years, Urban, ≤HS

Why is it always the blacks, everything has to be bad for the African Americans when it comes to disease, when it comes to health overall, when it comes to living in the community, when it comes to anything. Why does it always have to be African Americans that the risk of everything is so high?—Female, 30–45 years, Rural, >HS

It’s embarrassing to the Black community, the African-Americans. It’s like, like we a whole different breed or something… Why is everything falling on us like that? Is it just us just being stupid because of the culture we’re living in, or is it something that the government doing?—Male, 30–45 years, Urban, ≤HS

Was the STD disparity information believable?

The majority of participants found the information credible, recalling similar news or information from school or media. However, a minority expressed confusion, skepticism, or suspicion, questioning how such data could be collected or how rates could vary so significantly given that sexual activity occurs across all racial groups.

I think that no matter where people goes and what city they’re … they stay in, it’s a 50/50 chance, it’s a 50/50 chance that they can get it from White, Hispanic or Mexican or Black. There’s a 50/50 chance that they could get [an] STD.—Male, 18–29 years, Rural, ≤HS

People, we people. [laughter] What’s different? What’s different? [laughter] There ain’t no different. Everybody still be doing the same thing. You know what I’m saying, they might do, they might be on different, another different level, but everybody do the same thing.—Male, 30–45 years, Rural, ≤HS

Skeptical participants questioned the objectivity of data sources and sampling methods, suspecting that rates were based on public clinic data, leading to an overrepresentation of African-American cases and underreporting of other racial/ethnic groups. Some suggested government manipulation or fabrication of rates to encourage testing, while others doubted the reported low STD rates for other racial groups.

For years we have been the highest in this-and-that. It makes me feel disappointed and angry and maybe questionable. Where are you taking the survey from? Is it the local health clinic or doctors or where is the information coming from?—Male, 30–45 years, Urban, >HS

It’s been said that African Americans, I mean, the STD rates, AIDS and all of that stuff is high but I think when it comes to the White or Hispanic or whatever, maybe some people just don’t tell it, you know, when you’re rich, a lot of things can be hidden.—Female, 30–45 years, Rural, ≤HS

You get sick and tired of—somebody White come up with this. That’s the way I feel. This is crazy. Nasty as some Hispanics are, at least in the same ballpark as the Blacks. I just don’t buy it.—Male, 30–45 years, Rural, ≤HS

A few participants alluded to historical racism in America and government conspiracies against African Americans as potential causes for the disparities and perceived biased reporting.

How do they get that? I don’t understand that. I don’t know. And again, like I said, so much history has been taken away, even throughout history, so much … our history has been taken out of the textbooks and, I don’t know.—Female, 30–45 years, Rural, >HS

They [the government] say they give you opportunities. You got opportunity to go to college and all that but at the same time they put the poison on the street to bring you down again like they can’t raise you up.—Male, 30–45 years, Rural, >HS

Suggestions for improving data credibility and addressing concerns included providing transparent, verifiable sources like publicly accessible websites with data links, detailed descriptions of data collection methods (geographic areas, clinic/provider types reporting to CDC), explanations of rate calculation, and breakdowns of STD rates among African Americans by age, income, and education. To address suspected reporting biases, participants also sought information about included populations, such as whether immigrants and individuals with private insurance (presumed to be excluded) were accounted for. To enhance relevance, using more current data, presenting data in both numbers (STD cases) and rates, and including STD rates for other racial/ethnic minority groups were suggested.

Is disseminating this information considered important?

Despite some data skepticism, all participants agreed on the importance of raising awareness about the issue within African-American communities, noting that STDs are not currently a priority. Most felt that young people and those at highest risk should be the primary targets, although some believed the information should be shared community-wide due to universal risk.

I think young people and people who are at higher risk for STDs based on whatever numbers or statistics show.—Female, 18–29 years, Urban, >HS

I think that a lot of times we as a people deal with ‘Well, I don’t need to be bothered by that. My man is faithful or my woman is faithful’ … they think it doesn’t affect them, but it does.—Female, 30–45 years, Urban, >HS

They [African Americans] need to know that they can be part of this percentage if they don’t protect themselves and do the things to avoid getting any of these diseases.—Male, 18–29 years, Urban, ≤HS

What actions should follow the dissemination of this information?

Most participants believed the information would serve as a ‘harsh reality check’ to promote behavior change within African-American communities, particularly among youth and high-risk groups. Many stressed the importance of pairing data with STD prevention, testing, and treatment resources to empower individuals to protect themselves. Some suggested using graphic images of STD symptoms to ‘scare’ people into testing. A few advocated for positive framing and empowering messages, while others felt a combination of fear-based and positive messages would be most effective.

I would say to show it to them from more of a positive light because … when you scare people with the information, that’s what, what causes a lot of the negative like … the stereotypes towards people that have already gotten it or that people that have gotten it are scared to do anything about it or find out about it. That’s what makes them scared to find out.—Male, 18–29 years, Rural, >HS

When asked about disseminating this information to non-African-American communities, most participants questioned the purpose and reacted negatively, fearing offense, embarrassment, or insult. They explained it could stigmatize African Americans, reinforce negative stereotypes, and perpetuate racism and discrimination.

I would think it is useless because blacks would not see it and people who are seeing it—[it] is not really giving them their statistics but it is talking about black people. So it would not help blacks if it is not where they can access it.—Female, 18–29 years, Urban, ≤HS

They probably think: stay away from African Americans.—Male, 18–34 years, Rural, >HS

It would make people look at African Americans as if they are bad people and look down on us. They will say don’t have sex with black people and look at us as if we all have a disease because these numbers are so high.—Female, 30–45 years, Urban, ≤HS

Conversely, some participants, particularly in rural areas, thought it beneficial to inform all communities to promote universal awareness and self-protection, given the prevalence of interracial dating. A few also suggested it could initiate conversations about the issue across different communities.

STDs to me don’t have a color. It doesn’t have a race so everybody should be knowledgeable about it.—Female, 30–45 years, Rural, >HS

What type of information would most effectively reach African Americans and motivate change?

Participants suggested creative messaging methods for a hypothetical media campaign, emphasizing music and entertainment, celebrity endorsements, and personal stories from relatable individuals affected by STDs, rather than traditional health education approaches. Community group involvement at the local level was also deemed important. Finally, a multi-level approach with information from national, state, and local agencies across various sectors was suggested by some.

Discussion

This study represents the first qualitative exploration of STD perceptions and reactions to racially comparative STD data among African Americans in high-STD incidence communities. While many participants reported awareness of higher STD/HIV rates among African Americans, most were unaware of the ‘extent’ of racial STD/HIV disparities before being presented with CDC data. Disparities were largely attributed to individual behaviors, age, education, and poverty. The prevalent perception that STDs primarily affect ‘high-risk’ groups within African-American communities (e.g., youth, those with multiple partners, the poor and uneducated) highlights the need to reshape current beliefs about STD risk and susceptibility, reframing STDs as a community-wide issue relevant to all risk groups [9, 18]. The following discussion explores themes from participant reactions to racially comparative STD data and their implications for health communication strategies aimed at promoting sexual health equity.

Participant reactions to racially comparative STD data indicate that this information can raise significant alarm, drawing attention to the STD epidemic within African-American communities. While some participants expressed confusion or skepticism, almost all agreed on the critical need to disseminate this information within African-American communities as a prompt or ‘wake-up call’ for individual change, regardless of gender, age, urban/rural location, or education level. Most believed the information should target ‘high-risk’ groups and offered specific suggestions to enhance its acceptance. At minimum, the findings suggest strategic messaging to improve the information’s credibility, palatability, and relevance for African-American audiences. Transparency regarding data sources and collection methods is crucial, and messages should be delivered by trusted community sources. Statistics should be contextualized with explanations of underlying social determinants that influence sexual networks, individual choices, and access to care [29, 31], helping audiences understand that racial STD rate differences are not solely due to individual behavior. This should be coupled with concrete solutions at individual, community, and system levels to empower change, rather than fostering helplessness, as observed in this and other studies [29, 30].

However, several themes emerging from participant reactions suggest the need to reconsider how and whether to communicate racial disparities in STD rates to effectively reframe STDs as relevant to all African Americans and encourage adaptive individual responses. Firstly, strong feelings of distrust towards government and medical institutions, and suspicions of racism in STD/HIV prevention efforts, consistent with other research [41, 42], were voiced by some participants. Several also suspected data manipulation or fabrication by the government to promote behavior change. This raises questions about the effectiveness of government-collected statistics as a strategy for engaging African-American populations. Alternative information or messaging, developed and delivered within African-American communities, might be better received and acted upon to promote sexual health equity. Evidence suggests that general audiences, especially those with lower education and health literacy, struggle to understand or estimate personal risk based on numerical data [24]. Systematic evaluations of STD risk communication messages are needed to identify optimal formats for influencing STD risk perception and susceptibility [24, 43].

Secondly, experts caution that individuals may become defensive and question information that threatens their self-concept or referent group [32, 44]. This study indicates that racially comparative STD data could contribute to stigmatization both between and within groups, potentially leading to intergroup conflict rather than collective action. Some participants shifted focus to other racial/ethnic groups, suspecting data omissions or incompleteness and desiring to see STD rates for other minority groups and statistical breakdowns within the African-American population under the assumption that high rates are driven by specific subgroups. While acknowledging heterogeneity within the African-American population and including reassuring or ‘good news’ alongside STD statistics might be important, as opposed to solely emphasizing comparative failures [32], comparisons to worse-off populations may divert attention from the central issue. Focusing on highest-risk African-American subgroups could stigmatize vulnerable populations, reduce perceived risk among ‘less’ at-risk groups, and undermine efforts to frame STDs as a community issue relevant to all sexually active individuals [44–47].

Similarly, most participants (except for some rural respondents) expressed significant concerns about disseminating this information to non-African-American communities, fearing increased stigma, stereotypes, and discrimination. Other research cautions against broadly disseminating health or social statistics framed as racial disparities, as this can reinforce stereotypes of ‘separateness’ and distance minority concerns from the majority, even when communicated with good intentions by public health advocates [25, 26, 48].

Thirdly, it is crucial to question whether eliciting fear, distress, and despair is an ethical or effective approach to stimulating individual or social change, especially among vulnerable populations [27, 46]. Research suggests fear-based messages are effective when individuals have high self-efficacy and the resources to act on the information, but less effective when self-efficacy and resources are limited [46, 49]. Information generating fear or distress may exacerbate health inequities by triggering maladaptive responses among the most vulnerable, including anger, defensiveness, denial of personal relevance, message rejection, and fatalism [44, 46], as observed in this study. Experts suggest that repeated exposure to health disparity information may lead to ‘active avoidance, devaluation or rejection of the information’ by disproportionately affected populations [32]. Furthermore, threatening information can alienate audiences from the message source [46], potentially eroding trust in government or public health agencies within affected communities.

Participant calls for non-traditional health education methods reflect a shift away from this approach. While some participants recommended disseminating racial STD disparity data alongside fear tactics to ‘scare people’ into changing behavior, these suggestions should be interpreted cautiously. Firstly, participants may have been biased by the type of information presented in the study. Secondly, repeated use of fear appeals in real-world STD prevention messaging may have conditioned participants to expect a fear-based approach [46]. Fear appeals are often reported as highly motivating in research settings but may be less effective in real-world scenarios [46, 50]. Historically, traditional STD prevention efforts relying on fear-based messaging have stigmatized STDs and those affected, promoting silence, fear, and ignorance [47].

A shift towards a strength-based approach, building on individual and community resilience, particularly within marginalized communities, may be more appropriate [51]. Information emphasizing progress and appeals based on positive emotions (e.g., love, hope, empathy, empowerment, positive role models) may be equally or more effective in prompting desired attitudinal, behavioral, and social changes, while counteracting the negative effects of medical distrust among disproportionately affected populations [32, 44, 46]. This approach can foster positive relationships between public health agencies and affected communities [46], aligning with the broader public health shift from a disease/disparities focus towards health promotion and equity.

This exploratory research, intended to guide communication efforts for sexual health equity among vulnerable populations, focused on audience perceptions of the STD problem and reactions to statistics comparing STD rates across major racial/ethnic groups in the United States. It was limited to heterosexual adults from select U.S. communities with high rates of incarceration and STDs, who agreed to participate in health research (STD-testing history may be over-reported). Therefore, participant views and reactions to STD information or government statistics may differ from the general African-American population. The small sample size might also limit the detection of demographic subgroup differences. Other potentially relevant variables (e.g., incarceration history, STD-testing history) were not analyzed here, and some (e.g., health literacy, medical mistrust) were not assessed. Despite these limitations, this research advances the field by identifying potentially effective, appropriate, and acceptable information and messaging approaches for reaching African-American audiences, guiding communication efforts to promote sexual health equity.

Future research could test messages that frame or explain these statistics, assess the relative effectiveness of STD rates framed in absolute, positive, and disparity terms, and measure the impact on audience STD-related risk perceptions or behaviors. Comparing STD data to alternative information and messaging approaches that leverage positive emotions or community strengths is also warranted. Message-testing research should investigate audience characteristics that may influence message receptivity (e.g., health literacy, medical mistrust) and include vulnerable subpopulations (youth, gay/bisexual men) and potential unintended audiences (other racial or ethnic groups). Messages that minimize stigma, promote STDs as a relevant community issue for African Americans, and empower audiences to act should be piloted and evaluated within African-American communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ann Forsythe, Justin Smith, Shelly Harris, Hilda Shepeard, and Susan Robinson for their contributions to this research.

Funding

This research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (contract number 200-2007-20016/0004).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

[1]Glynn RW, Ahern RE, Hickey L, נאך גערעדט פֿאַרלאַנגט נאָך כאַראַקטעריסטיקס פון באַוווסטזיניק שוועסטערייַ זאָרגן און זייַן ימפּלאַקיישאַנז פֿאַר שוועסטערייַ בילדונג. J Adv Nurs. 2019 Feb;75(2):273-285. doi: 10.1111/jan.13847. Epub 2018 Oct 26. PMID: 30246498.

[2] Hoover KW, Tao G, Kent CK, Klausner JD, Liddon N, Brouillard V, Weinstock H; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Progress and challenges in reducing racial disparities in rates of gonorrhea–United States, 1999-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009 Apr 24;58(15):401-5. PMID: 19390399.

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2007. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008.

[4] U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates Program. [cited 2009 Aug 12]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/NC-EST2008-sa.html

[5] Adimora AA, Hamilton H, Underwood J, Dinganga M, Martinson F, Bellis JR, Leone PA, Fiscus SA. Gonorrhea and chlamydial infection among women in the South: associations with race and place. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Feb;34(2):75-80. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318028aa58. PMID: 17033505.

[6] Aral SO, Fenton KA. Testing for sexually transmitted infections in the United States: why, who, when, and where. Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Feb;36(2 Suppl):S3-9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181933a90. PMID: 19158657.

[7] Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The social organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994.

[8] Ellenberg JH, Johnson WD, Leone PA, Adimora AA, Weissman J, Zenilman JM, Ness RB, Swygard H, Schwebke JR, Mena L, Hillier SL, Gaydos CA, Fiscus SA, Quinn TC, Brookmeyer RS; STDCSU Investigators. Concurrent partnerships, HIV incidence, and gonorrhea prevalence in African Americans in 5 US cities. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Nov;34(11):847-54. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181425044. PMID: 17592391.

[9] Zenilman JM. Syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia: don’t blame it on me. Sex Transm Dis. 2007 Feb;34(2):73-4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318028ac75. PMID: 17224717.

[10] Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural determinants of racial disparities in HIV transmission and progression. AIDS. 2006 Suppl 1:S87-96. PMID: 17183037.

[11] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS among African Americans. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007.

[12] Fenton KA, Chin J. Syphilis in the United States: what’s happening now? Am J Public Health. 2007 Dec;97(12):2138-43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115879. Epub 2007 Oct 31. PMID: 17971531.

[13] Latkin CA, Forman V, Knowlton AR, Sherman S. Norms, social networks, and HIV risk behaviors among African American drug users in Baltimore. AIDS Behav. 2003 Sep;7(3):239-48. PMID: 12955122.

[14] Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Hamilton HL, Martinson FE, McGee F, Fiscus SA, Leone PA. Effect of black-white racial segregation on gonorrhea rates in the United States, 1990-2000. Sex Transm Dis. 2005 Aug;32(8):477-83. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000167457.83513.a2. PMID: 16044097.

[15] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A vision for CDC STD prevention. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007.

[16] Kaiser Family Foundation. Race, ethnicity and HIV/AIDS. Menlo Park (CA): The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009.

[17] Freimuth VS, Quinn SC. The contributions of health communication to eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2004 Feb;94(2):263-5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.263. PMID: 14759623.

[18] Kershaw TS, Ethier KA, Niccolai L, Lewis JB, Milanov V, Ickovics JR. Redefining risk? African American women and perceptions of HIV risk. AIDS Behav. 2006 Nov;10(6):717-27. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9121-9. PMID: 16732417.

[19] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National stakeholder strategy for achieving health equity. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

[20] Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002 Jul;94(7):666-8. PMID: 12108624.

[21] Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

[22] Murray CJ, Kulkarni SC, Ezzati M. Eight Americas: investigating mortality disparities across races, counties, and race-counties in the United States. PLoS Med. 2006 Sep;3(9):e260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030260. Epub 2006 Aug 29. PMID: 16930115.

[23] Krieger N. Epidemiology and the people’s health: theory and context. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

[24] Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Byram SJ, Fischhoff B, Welch HG. The risk of using numbers to describe risk. Med Decis Making. 2001 Jul-Sep;21(4):249-58. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100401. PMID: 11478489.

[25] Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Intergroup bias. In: Hogg MA, Cooper J, editors. The Sage handbook of social psychology. London: Sage Publications; 2007. pp. 453-82.

[26] Entman RM, Page N. The Black image in the white mind: media and race in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2001.

[27] Ragan SL,街头霸王, Whitten PS, Allen M. Health communication: theory and application. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2005.

[28] Brashers DE, Goldsmith DJ. Threat and coping in health communication. In: Thompson TL, Dorsey EA, Miller-Day M, editors. Handbook of health communication. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. pp. 199-224.

[29] Corbie-Smith C, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999 Feb;14(2):89-96. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00294.x. PMID: 10071572.

[30] Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997 Nov;87(11):1773-8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. PMID: 9366635.

[31] Katz IR, Kegeles SM. The impact of the AIDS epidemic on the psychosocial aspects of African American life. AIDS Educ Prev. 1991 Summer;3(2):71-9. PMID: 1889544.

[32] Nicholson S, Zhang Y, Kobetz E, Consedine NS. Disparity messaging and intentions to screen for colorectal cancer among African Americans. Health Psychol. 2011 Jul;30(4):491-9. doi: 10.1037/a0023533. PMID: 21787108.

[33] Chapman S, Lupton D. “Best practice” in media health promotion. In: Chapman S, Lupton D, editors. The fight for public health: principles and practices of media advocacy. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1994. pp. 93-108.

[34] Kreps GL, Street RL Jr. Communication as constitutive of organizing and organizing as constitutive of communication. In: Kreps GL, Street RL Jr, editors. An analysis of organizational communication. New Jersey: Hampton Press; 2002. pp. 3-38.

[35] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National notifiable diseases surveillance system. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007.

[36] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlas of STD rates among African Americans. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007.

[37] Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967.

[38] Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park (CA): Sage Publications; 1990.

[39] D’Andrade RG. Cultural schemas and motivation. In: D’Andrade RG, Strauss C, editors. Human motives and cultural models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 23-44.

[40] Strauss C, Quinn N. A cognitive theory of cultural meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997.

[41] Bogart LM, Bird ST, Bogart A, Del Rio C, Telesmanich J, Wagner GJ. Conspiracy beliefs and HIV risk behaviors among African Americans in Los Angeles. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 May 1;48(1):100-6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816b7c7c. PMID: 18388544.

[42] Semenya KA, Abel J, Ingram RC, Broadhead RS, Heckert KA, Cottler LB, Wampler J. Beliefs about the origin of AIDS and multiple sexual partners among African Americans with drug abuse histories. Sex Transm Dis. 2001 May;28(5):299-307. doi: 10.1097/00002294-200105000-00007. PMID: 11359137.

[43] Noar SM, Palmgreen P, Chabot M, Dobransky N, Zimmerman RS. Testing the theory of planned behavior and fear appeals to change adolescent risky driving. Health Psychol. 2004 Sep;23(5):548-55. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.548. PMID: 15367012.

[44] Sherman DK, Nelson LD. Defensive processing of health risk communications: mechanisms and impact. Health Psychol. 2008 Sep;27(5):S103-13. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.S103. PMID: 18823219.

[45] Aral SO, Washington AE. Sexually transmitted diseases: magnitude of the problem. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Mardh PA, Lemon SM, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. pp. 39-62.

[46] Witte K, Allen M. Health risk messages: processing negative emotions. In: Dillard JP, Shen L, editors. The SAGE handbook of persuasion: developments in theory and practice. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2007. pp. 513-30.

[47] Brandt AM. No magic bullet: a social history of venereal disease in the United States since 1880. New York: Oxford University Press; 1987.

[48] Gilens M. Why Americans hate welfare: race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999.

[49] Ruiter RA, Kessels LT, Jansma BM, O’Brien K, Kok G. Increasing the effectiveness of fear appeals in health promotion by focusing on response efficacy. Psychol Health. 2014;29(1):26-43. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.821559. Epub 2013 Aug 8. PMID: 23924494.

[50] de Hoog N, Stroebe W, de Wit JB. The impact of fear-arousing communications on attitude change: an integrative framework. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2007 Aug;11(3):273-303. doi: 10.1177/1088868307303520. PMID: 17622648.

[51] Saleebey D. The strengths perspective in social work practice. 5th ed. Boston: Pearson Education; 2006.