Abstract

Simple Summary

Lymphoma incidence and mortality rates are higher in males than females, a disparity potentially linked to metabolic differences, notably visceral obesity. Visceral fat, a marker for poorer health outcomes, is typically higher in males. This study reveals that while males with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) have more visceral fat, it paradoxically predicts worse outcomes specifically in females. Females who gained visceral fat during chemotherapy also fared worse. Combining visceral fat changes during treatment with post-treatment tumor glucose uptake identified a very high-risk subgroup of females.

Abstract

Sex disparities in cancer, including lymphoma, show males with increased incidence and mortality. Emerging research points to sex-based metabolic differences, encompassing both tumor metabolism and systemic changes like obesity, as a contributing factor. This study investigated whether visceral fat and tumor glucose uptake, as measured by fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT), could predict sex-specific outcomes in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). A retrospective analysis of 160 DLBCL patients (84 males, 76 females) with imaging at initial staging and post-therapy was conducted. CT-derived relative visceral fat area (rVFA), PET-derived SUVmax normalized to lean body mass (SULmax), and end-of-treatment FDG-PET 5-point scale (5PS) scores were calculated. Elevated rVFA at initial staging independently predicted poorer overall survival (OS) solely in females. Increased visceral fat post-therapy also significantly predicted worse survival in females only. Integrating rVFA changes and 5PS scores identified a female subgroup with visceral fat gain and high 5PS exhibiting exceptionally poor outcomes. These findings suggest visceral fat and tumor FDG uptake are sex-specifically predictive of outcomes in DLBCL.

Keywords: lymphoma, DLBCL, visceral fat, glucose metabolism, sex differences, FDG-PET, body composition, CT, Usa Sex Guide Ct (This keyword is included as per instruction, but is not relevant to the content and for SEO purposes should be ignored in favor of the more relevant keywords)

1. Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most prevalent non-Hodgkin lymphoma globally, with over 18,000 new annual diagnoses in the United States. While initial treatment with rituximab and anthracycline-based therapies aims for a cure, the 3-year event-free survival (EFS) rate varies from 53% in older, high-risk patients to 79% in younger, low-risk patients based on the International Prognostic Index (IPI) [1,2,3]. Prognosis is known to be influenced by clinical risk factors and histological characteristics like cell of origin and genetic translocations involving MYC, BCL2, and BCL6. Prognostic systems like the IPI help stratify DLBCL patients to guide treatment strategies. Sex-based prognostic differences are observed in various cancers, including DLBCL, where males consistently show poorer outcomes compared to females treated with rituximab-based therapy [4]. Understanding the mechanisms behind this sex disparity is crucial for refining outcome predictions and elucidating DLBCL pathogenesis.

Elevated glucose metabolism is a hallmark of cancer and the principle behind fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) imaging. Nutrient uptake and metabolic processes are not only critical for cancer survival but also exhibit sexual dimorphism. Males, developmentally, are characterized by enhanced glucose metabolism and greater visceral obesity compared to females [5,6,7]. Visceral fat is directly linked to adverse cancer and cardiovascular outcomes [8,9,10,11,12]. Therefore, inherent sex differences in metabolism may contribute to the observed sex disparity in cancer outcomes.

Our research group has previously contributed to this understanding. We’ve shown that increased glycolysis in low-grade gliomas predicts poorer outcomes in males, but not females [13]. We also found that visceral fat, despite being more prevalent in males with renal cell carcinoma (RCC), selectively risk-stratified females, not males [14]. Building upon these findings, this retrospective study aimed to determine if quantitative metabolic markers of glucose uptake and visceral fat, obtained from FDG-PET/CT, could predict sex-specific outcomes in DLBCL patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical, Metabolic, and Pathologic Data

With institutional review board approval, a retrospective study was conducted on de novo DLBCL patients consecutively treated at Washington University in St. Louis from 2006 to 2016. Medical records were reviewed to collect baseline patient characteristics: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and diabetes status. Pathological data included DLBCL subtype (cell of origin) and presence of MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 translocations. Treatment regimens and clinical features like stage, IPI score, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and extranodal sites were also recorded.

2.2. Software

Vitrea Fat Measurement Application (Vital Images, Minnetonka, MN, USA) license was provided by the manufacturer for fat segmentation analysis. PET imaging data was quantified using a Hermes workstation (Hermes Medical Solutions, Greenville, NC, USA).

2.3. Imaging Analysis

FDG-PET/CT scans were performed at baseline and end of treatment (4–8 weeks post-chemotherapy), as standard practice. SUVmax, the maximum standardized uptake value within a 3D region of interest around the most metabolically active lesion, was recorded. To account for sex-specific obesity effects on FDG uptake, SUVmax was converted to SULmax using the Janmahasatian formula for lean body mass (LBM) estimation in males and females, as previously described [15]. Delta SULmax was calculated as the percentage change from initial to end-of-treatment SULmax.

Fat segmentation was performed as previously detailed [14,16]. CT images from PET/CT scans were analyzed using the Vitrea Fat Measurement Application. Subcutaneous and visceral fat areas (SFA and VFA) at the umbilical level were mapped using Hounsfield Unit (HU) thresholds from -150 to -35. Manual corrections were made to software-defined areas, excluding enteric, colonic, and epidural fat. Total fat area (TFA) was the sum of SFA and VFA. Relative VFA (rVFA) was calculated as VFA percentage of TFA (rVFA = VFA/TFA) [14] (Figure S1). Delta rVFA represented the percentage change from initial to end-of-treatment rVFA.

Fasting blood glucose and maximum SUV of total lymphoma tumor burden (SUVmax) were obtained from PET data. Deauville 5-point score (5PS) criteria were used to determine end-of-treatment 5PS scores.

2.4. Treatment Regimens

Most patients received rituximab-based therapy. 95 patients (59.4%) received RCHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine, and prednisolone), 21 (13.1%) REPOCH (RCHOP with etoposide), and 6 (3.8%) RCEOP (rituximab, vincristine, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and prednisolone). 37 patients (23.1%) were treated with RCHOP-based regimens within clinical trials involving other agents. One patient received off-label CHOP with lenalidomide.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median (range), and categorical variables as proportions. Sex-based comparisons used the Mann–Whitney test for continuous and chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. A biomarker cutoff optimization algorithm determined optimal metabolic value thresholds for survival stratification in males and females [14,17].

Kaplan–Meier method estimated overall survival, and log-rank test compared survival differences. Cox proportional hazards regression assessed the risk of rVFA, SULmax, and BMI, adjusting for clinical factors. Proportional hazard assumptions were verified using martingale residual cumulative sums.

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5.04 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) software. Two-tailed tests were used where applicable, with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

We analyzed 160 patients; baseline characteristics are in Table 1. The cohort included 76 males (47.5%) and 84 females (52.5%), with mean diagnosis ages of 58 and 62 years (range 21–92), respectively. Males showed a trend towards lower ECOG performance status (p = 0.07) and higher LDH (p = 0.058), but other risk factor frequencies were similar between sexes.

Table 1. Clinical and pathologic characteristics for patients in this study.

| Factor | Total (N = 160) | Female (N = 84) | Male (N = 76) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 60.0 [21.0–92.0] | 62.0 [26.0–92.0] | 58.0 [21.0–84.0] | 0.142 |

| Length of Follow-up (months) | 34.7 [2.2–136.8] | 39.8 [2.2–136.8] | 31.6 [3.5–122.0] | 0.576 |

| GCB * | 1.00 | |||

| No | 58 (42.6) | 30 (42.9) | 28 (42.4) | |

| Yes | 78 (57.4) | 40 (57.1) | 38 (57.6) | |

| MYC FISH | 0.756 | |||

| positive | 11 (6.9) | 6 (7.1) | 5 (6.6) | |

| negative | 90 (56.3) | 43 (51.2) | 47 (61.8) | |

| N/A | 59 (36.9) | 35 (41.7) | 24 (31.6) | |

| BCL2 FISH * | 0.788 | |||

| positive | 16 (10.0) | 7 (8.3) | 9 (11.8) | |

| negative | 74 (46.3) | 36 (42.9) | 38 (50.0) | |

| N/A | 70 (43.8) | 41 (48.8) | 29 (38.2) | |

| BCL6 FISH * | 0.777 | |||

| positive | 16 (10.0) | 7 (8.3) | 9 (11.8) | |

| negative | 54 (33.8) | 28 (33.3) | 26 (34.2) | |

| N/A | 90 (56.3) | 49 (58.3) | 41 (53.9) | |

| IPI at diagnosis * | 0.959 | |||

| 0 | 15 (9.4) | 8 (9.5) | 7 (9.3) | |

| 1 | 34 (21.4) | 20 (23.8) | 14 (18.7) | |

| 2 | 42 (26.4) | 21 (25.0) | 21 (28.0) | |

| 3 | 45 (28.3) | 22 (26.2) | 23 (30.7) | |

| 4 | 14 (8.8) | 8 (9.5) | 6 (8.0) | |

| 5 | 9 (5.7) | 5 (6.0) | 4 (5.3) | |

| LDH | 0.058 | |||

| Normal | 74 (46.3) | 45 (53.6) | 29 (38.2) | |

| Abnormal | 86 (53.8) | 39 (46.4) | 47 (61.8) | |

| ECOG | 0.228 | |||

| 0 | 74 (46.3) | 36 (42.9) | 38 (50.0) | |

| 1 | 62 (38.8) | 31 (36.9) | 31 (40.8) | |

| 2 | 18 (11.3) | 12 (14.3) | 6 (7.9) | |

| 3 | 6 (3.8) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (1.3) | |

| ECOG | 0.074 | |||

| 0 or 1 | 136 (85.0) | 67 (79.8) | 69 (90.8) | |

| 2 or 3 | 24 (15.0) | 17 (20.2) | 7 (9.2) | |

| Initial Treatment | 0.274 | |||

| RCHOP | 95 (59.4) | 52 (61.9) | 43 (56.6) | |

| REPOCH | 21 (13.1) | 7 (8.3) | 14 (18.4) | |

| RCEOP | 6 (3.8) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Other | 38 (23.8) | 21 (25.0) | 17 (22.4) | |

| BMI | 0.867 | |||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 53 (33.1) | 27 (32.1) | 26 (34.2) | |

| BMI < 30 | 107 (66.9) | 57 (67.9) | 50 (65.7) | |

| Type 2 Diabetes Diagnosis | 0.659 | |||

| Yes | 24 (15.0) | 14 (16.7) | 10 (13.2) | |

| No | 136 (85.0) | 70 (83.3) | 66 (86.8) |

* Data not available for all subjects. Values presented as Median [min–max] or N (column %).

DLBCL molecular subtype status was available for 136 patients: 78 (57.4%) germinal center B-cell (GCB) and 58 (42.6%) non-GCB subtype. Median IPI score was 2 for both sexes. ECOG performance status was 0 or 1 for 136 patients (85.0%) and 2 or 3 for 24 patients (15.0%).

The 5-year overall (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) for the entire cohort were 78.8% and 73.3%, respectively. Males trended towards worse OS and PFS compared to females, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 1). Stratification by cell of origin showed 5-year OS for GCB subtype at 80.3% versus 73.1% for non-GCB (p = 0.138; Figure S1). Similarly, 5-year PFS for GCB was 76.3% versus 64.8% for non-GCB (p = 0.060; Figure S1). IPI stratification showed a significant trend towards worse OS (p = 0.038) and PFS (p = 0.014) with increasing IPI risk groups (Figure S1). Treatment regimen stratification showed no PFS (p = 0.18) or OS (p = 0.50) differences, consistent with studies showing no superiority of novel regimens or DA-R-EPOCH over RCHOP [1,18].

Figure 1. Survival of the DLBCL Patient Cohort.

(A) Overall Survival and (B) Progression-Free Survival. Survival curves are shown for all patients, females, and males. p-value (female vs. male survival) from log-rank test.

BMI impact was also assessed. No BMI difference existed between sexes (Table 2). Using a BMI threshold of >30 kg/m2 for obesity, OS and PFS were evaluated for the entire cohort and by sex. Obese patients trended towards better 5-year PFS (83% vs. 68.2%, p = 0.064). This was prominent in males. Obese males (n = 26) had better 5-year PFS (86.2%) compared to other males (57.8%; p = 0.036). No significant obesity effects on female PFS (p = 0.903) were observed. Obesity effects on OS in males and females were not significant (Figure S2).

Table 2. Summary of Patient Metabolic Parameters.

| Parameters | Total(N = 160) | Male(N = 84) | Female(N = 76) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-therapy BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 [15.1–49.1] | 27.2 [15.1–49.1] | 27.2 [15.5–44.3] | 0.957 |

| Pre-therapy rVFA (%) | 35.3 [15.1–78.9] | 40.5 [17.9–78.9] | 30.4 [15.1–73.0] | <0.001 |

| Post-therapy rVFA (%) * | 35.3 [14.7–80.9] | 40.9 [17.0–63.1] | 32.3 [14.7–80.9] | <0.001 |

| Delta rVFA (%) * | 2.4 [−54.9–89.6] | −3.0 [−54.9–79.0] | 7.8 [−32.2–89.6] | 0.001 |

| Pre-therapy Fasting Serum Glucose (mg/dL) * | 98.0 [68.0–189.0] | 96.0 [68.0–189.0] | 100.0 [70.0–179.0] | 0.146 |

| Pre-therapy SULmax | 15.9 [3.1–51.2] | 17.8 [3.1–51.2] | 15.1 [1.2–33.2] | 0.007 |

| Post-therapy SULmax * | 1.5 [0.7–24.3] | 1.9 [0.7–24.3] | 1.2 [0.7–14.9] | <0.001 |

| Delta SULmax * | −88.8 [−97.1–128.5] | −88.8 [−97.0–128.5] | −89.3 [−97.1–−7.1] | 0.241 |

Values presented as median [range]. * Data not available for all subjects.

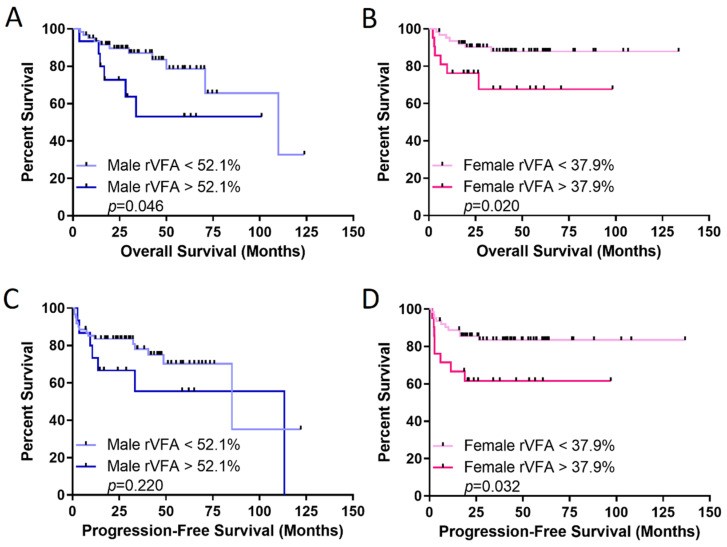

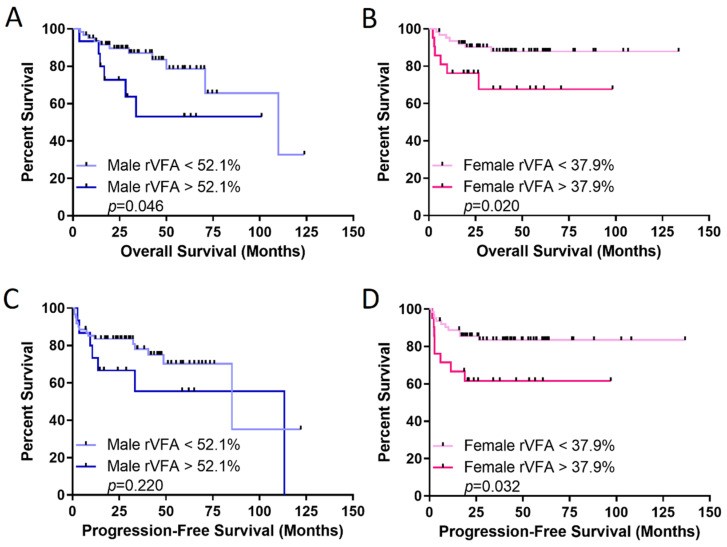

3.2. Effects of rVFA on Survival

Initial staging rVFA effect on OS and PFS was evaluated. rVFA was significantly higher in males (Table 2). No correlation existed between rVFA and BMI in either sex (Figure S3). Using an optimal female rVFA threshold of 37.9%, females with rVFA above threshold had significantly worse OS and PFS (p = 0.020 and 0.032, respectively). In males, rVFA above the optimal 52.1% threshold was associated with worse OS, but not significantly different PFS (Figure 2). Multivariate analysis controlling for age, LDH, extranodal sites, and stage confirmed rVFA threshold effect on OS and PFS only in females (Table 3 and Table 4). Controlling for cell of origin also maintained rVFA threshold significance for OS in females (HR = 0.311, p = 0.049) but not males (HR = 0.721, p = 0.564). Similar PFS patterns were observed, with female HR 0.225 (p = 0.006) and male HR 0.710 (p = 0.470).

Figure 2. Relative visceral fat area (rVFA) is a better predictor of survival in females with DLBCL.

Overall survival (OS) in (A) males and (B) females, and progression-free survival in (C) males and (D) females. rVFA thresholds were identified with optimized biomarker threshold algorithm. p-value from log-rank test.

Table 3. Overall Survival (OS) multivariate Cox regression analysis for rVFA.

| Characteristic | Male HR (95% CI) | Male p-Value | Female HR (95% CI) | Female p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.148 (0.391–3.373) | 0.801 | 0.519 (0.161–1.680) | 0.274 |

| LDH | 1.358 (0.441–4.181) | 0.594 | 3.582 (0.908–14.124) | 0.068 |

| Extranodal status | 0.799 (0.264–2.414) | 0.691 | 0.988 (0.300–3.255) | 0.984 |

| Stage | 1.513 (0.377–6.081) | 0.560 | 1.508 (0.351–6.478) | 0.581 |

| rVFA cutoff | 2.303 (0.779–6.806) | 0.131 | 3.694 (1.132–12.050) | 0.030 |

Table 4. Progression-Free Survival (PFS) multivariate Cox regression analysis for rVFA.

| Characteristic | Male HR (95% CI) | Male p-Value | Female HR (95% CI) | Female p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.187 (0.461–3.057) | 0.722 | 0.584 (0.215–1.587) | 0.292 |

| LDH | 1.540 (0.549–4.317) | 0.412 | 3.274 (1.066–10.058) | 0.038 |

| Extranodal status | 0.896 (0.346–2.322) | 0.821 | 0.949 (0.350–2.570) | 0.918 |

| Stage | 1.453 (0.446–4.730) | 0.535 | 1.057 (0.327–3.417) | 0.926 |

| rVFA cutoff | 1.451 (0.561–3.753) | 0.443 | 3.199 (1.166–8.772) | 0.024 |

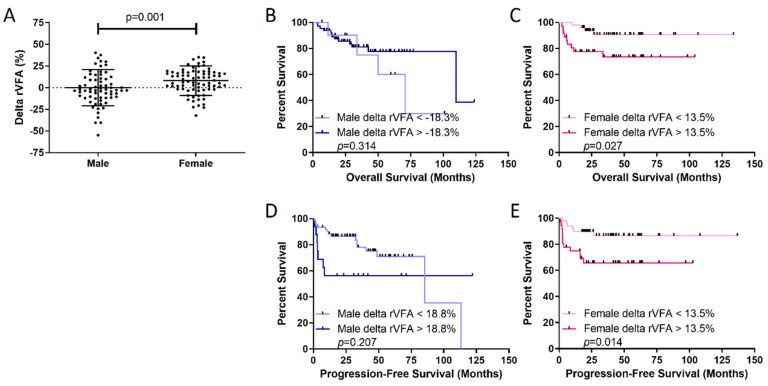

Delta rVFA was calculated to assess chemotherapy response effects on visceral obesity. Delta rVFA significantly differed between sexes. Males had median delta rVFA of -3.0%, while females had +7.8%, indicating visceral fat gain in females post-chemotherapy (p = 0.001; Table 2, Figure 3). Analysis of female fat stores showed rVFA increase due to SFA loss (initial median: 270 cm2 vs. EOT: 246 cm2; p = 0.002) with no VFA change (initial median: 127 cm2 vs. EOT: 122 cm2; p = 0.771). Delta rVFA effects on sex-specific survival were assessed. Females with delta rVFA >+13.5% (visceral fat gain) had significantly worse OS (p = 0.027) and PFS (p = 0.014) compared to those below 13.5% (Figure 3). No delta rVFA threshold identified males with poorer OS or PFS (Figure 3), mirroring initial staging rVFA data.

Figure 3. Visceral fat is gained in females during chemotherapy and predicts poor outcomes in females.

(A) Females gain more visceral fat than males during therapy, measured by delta rVFA. Overall survival (OS) in (B) males and (C) females and progression-free survival in (D) males and (E) females show that higher delta rVFA predicts poorer female outcomes. Delta rVFA thresholds were identified with optimized biomarker threshold algorithm. p-value from log-rank test.

BMI was compared between high and low delta rVFA groups using cutoffs of 18.8% in males and 13.5% in females from Figure 3. No significant BMI differences existed between delta rVFA groups (Figure S4), supporting the lack of BMI and rVFA correlation.

3.3. Integration of Delta rVFA and FDG-PET Measurements

End-of-treatment 5PS score effect on sex-specific outcomes was evaluated, as 5PS is crucial for outcome prediction and therapeutic response assessment. 5PS was dichotomized into low (1–3) and high (4–5) groups. High 5PS scores were associated with shorter OS and PFS in all patients, males, and females (Figure S5).

Delta SULmax was calculated similarly to delta rVFA. SULmax values at both initial staging and end-of-therapy were significantly higher in males (Table 2). High 5PS scores correlated with significantly higher delta SULmax (residual uptake) in both sexes (Figure S6).

The synergistic effect of visceral fat and tumor glucose metabolism previously observed in female RCC [14] was assessed for delta rVFA and end-of-treatment 5PS score. Combining dichotomized delta rVFA and 5PS groups, OS and PFS differences were assessed in males and females separately. In males, 5PS score primarily drove outcomes, with high 5PS associated with shorter OS and PFS (Figure 4). However, in females, the combination of increased visceral fat gain and high 5PS score identified a subset with significantly poorer outcomes. This female subgroup (n = 8) had 5-year PFS of 37.5% (p = 0.001) and 5-year OS of 50% (p < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Synergy of delta rVFA and end-of-treatment 5PS score identifies females with poor survival.

K-M curves depict four combinations of high/low delta rVFA and 5PS scores for males (A,C) and females (B,D). Overall survival data in (A,B) and progression-free survival in (C,D). Females with both high delta rVFA and high 5PS at end-of-treatment had significantly shorter OS (B) and PFS (D) compared to other female groups. Male OS and PFS are primarily defined by end-of-therapy 5PS score, not delta rVFA. p-value from log-rank test.

3.4. Effects of Diabetes or Fasting Glucose on Survival

The relationship of metabolism with these findings was further explored by investigating fasting serum glucose effects at initial staging or end-of-treatment FDG-PET on male and female OS and PFS. No significant associations were found (data not shown). However, analyzing OS and PFS by sex and type 2 diabetes diagnosis revealed that diabetic males trended towards worse PFS (p = 0.051, Figure S7) and had significantly worse OS (p = 0.004), with median OS of 40 months versus 110 months in non-diabetic males. Intriguingly, diabetes status showed no significant effects on OS (p = 0.869) and PFS (p = 0.981) in females (Figure S7).

4. Discussion

Males experience worse cancer outcomes across various types, including lymphomas like Hodgkin lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and DLBCL [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Metabolism, a cancer hallmark, is a potential key factor in this sex disparity [27]. Developmental sex differences in metabolism exist from early development into adulthood; males tend to rely more on glucose and amino acid oxidation for energy, while females favor lipid metabolism [28,29,30,31].

Our group has advanced this understanding by demonstrating that increased glucose metabolism in lower-grade glioma tumors is linked to male-specific poor OS [13]. We further showed increased glutamine metabolism in normal human male brains and male glioblastoma [32], indicating sex differences in normal metabolism are reflected in cancer. While tumor tissue molecular profiling was unavailable in this study, we used FDG-PET imaging, a clinically relevant marker for tumor glucose uptake. Notably, SULmax at initial staging and end-of-therapy was significantly higher in males. Schöder et al. reported that in the CALGB 50303 DLBCL study, interim SUV change predicted outcomes, but baseline SUVmax did not, without examining sex-specific differences [33]. Some studies suggest sex-specific outcome differences may be due to males potentially benefiting from higher rituximab doses. Our study used standard rituximab dosing (375 mg/m2), and outcomes were similar in sexes without rVFA stratification [34].

BMI’s prognostic effect in lymphoma is debated, with mixed findings: some studies show better outcomes in obese patients, others worse, and some no effect [35,36,37,38,39]. This heterogeneity may relate to disease variability; BMI is also an indirect obesity measure, influenced by muscle mass. Patients with identical BMIs can have differing fat and muscle amounts [40]. Intriguingly, our cohort suggested BMI might predict better outcomes in males but not females, while rVFA predicted poorer outcomes in females but not males. This implies muscle may play a role in male outcomes, requiring further study.

To our knowledge, we are the first to report sex- and treatment-dependent visceral fat differences (rVFA) in lymphoma. rVFA changes during treatment were more pronounced in females. Combining delta rVFA and end-of-treatment 5PS, females with increased visceral fat (high delta rVFA) and incomplete remission (high 5PS) had particularly poor survival. This was not observed in males with high delta rVFA and 5PS. These findings suggest treatment response and outcomes are partly dependent on patient sex and metabolism. Sex differences exist in corticosteroid response, a component of DLBCL chemotherapy (prednisone), affecting glucose homeostasis sex-specifically, more significantly in females [41,42,43,44,45].

Recent studies link type 2 diabetes diagnosis to worse DLBCL outcomes [46,47], but sex-specific differences were unreported. In our study, diabetes significantly negatively impacted male OS (p = 0.004). This might relate to sex differences in glucose homeostasis; males have lower insulin sensitivity and higher diabetes incidence [5,6]. Interestingly, fasting serum glucose levels at initial staging or end-of-treatment did not correlate with outcomes. These results suggest “metabolically resistant” tumors or circulating glucose levels might have sex-specific implications, possibly due to cell-intrinsic metabolic differences, sex hormone effects, and/or tumor genetic alterations affecting glucose metabolism and proliferation. A retrospective study showing metformin use associated with favorable prognosis in diabetic DLBCL patients supports this [48]. Prospective clinical trial validation is needed.

Our study is limited by its retrospective, single-institution nature, requiring validation in multicenter prospective databases. However, similar findings in renal cell carcinoma regarding tumor glycolysis and visceral fat strengthen our results [14]. We focused on frontline curative therapy, but rVFA impact in relapsed/refractory settings warrants investigation as DLBCL treatment evolves [49]. While patients received varied RCHOP-based regimens, no outcome differences based on regimen were observed, minimizing confounding. Despite limitations, this study adds to growing evidence supporting sex and metabolism as crucial biological variables in cancer treatment response.

5. Conclusions

Despite limitations, including the retrospective design and lack of genomic, transcriptomic, or metabolomic correlations, our findings align with existing data. They support an emerging paradigm of utilizing systemic and tumor metabolism for patient risk stratification and developing metabolism-targeted interventions for improved survival. Regardless of mechanisms behind sex differences in survival related to tumor glucose uptake and visceral fat, clinical metabolic interventions exist to target these metabolic facets sex-specifically. For instance, anti-diabetic drugs like sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors can potentially directly inhibit tumor glucose metabolism while reducing visceral fat [50,51,52,53]. These could supplement dietary and exercise regimens to enhance outcomes for patients undergoing curative DLBCL treatment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information is available online at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers14122932/s1, Figure S1: Impact of DLBCL prognostic classifiers on patient survival. Figure S2: Impact of obese BMI on patient survival. Figure S3: Correlation analyses of BMI and rVFA. Figure S4: Effect of delta rVFA groups on BMI. Figure S5: High 5PS score association with decreased OS and PFS. Figure S6: Higher 5PS scores and increased delta SULmax values. Figure S7: Worse survival in diabetic males with DLBCL compared to females.

Click here for additional data file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.I. and N.M.-S.; methodology, J.E.I. and N.M.-S.; formal analysis, S.J., V.S., P.P., S.T., A.S., N.M.-S., and J.E.I.; data curation, S.J., V.S., P.P., S.T., M.P.W., and N.A.; resources, D.R.L., J.M., V.M.M., N.L.B., B.S.K., T.A.F., A.G., A.F.C., N.M.-S., and J.E.I.; validation, S.J., V.S., P.P., and A.S.; investigation, S.J., V.S., and P.P.; supervision, L.R.P.; visualization, N.M.-S. and J.E.I.; writing—original draft, S.J., V.S., P.P., S.T., N.M.-S., and J.E.I.; writing—review and editing, S.J., V.S., P.P., S.T., A.S., M.P.W., N.A., D.R.L., J.M., V.M.M., L.R.P., N.L.B., B.S.K., T.A.F., A.G., A.F.C., N.M.-S., and J.E.I.; funding acquisition, N.M.-S. and J.E.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board (protocol code 20170617, approved June 29, 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

J.E.I. and V.M.M. receive research support from Vital Images for Vitrea FatQuant Application. Vital Images had no influence on data analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation. N.M.S. has institutional research funding from Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Verastem Pharmaceuticals, Innate Pharmaceuticals, Corvus Pharmaceuticals and has consulted for Kyowa Hakka Kirin, C4 Therapeutics, and Karyopharm.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by NIH grants R21CA242221 (J.E.I.), R00CA218869 (J.E.I.), UL1TR002345 (J.E.I.), K12CA167540 (N.M.S.); Lymphoma Research Foundation grant 610181 (N.M.S.); and Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation (J.E.I.). The authors acknowledge the TREC Training Workshop R25CA203650.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI remains neutral regarding jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[References listed in the original article]

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

Click here for additional data file.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.