Language field guides offer an innovative approach for educators and students to delve into the richness of language. They serve as a tool for discovery, allowing both readers and writers to explore the nuances of words and their impact on meaning. This method shifts the focus of vocabulary instruction from rote memorization to meaningful exploration, aligning with key educational values such as student choice, voice, inquiry, and agency. By bridging the gap between reading and writing, language field guides become a cornerstone for language study in the classroom.

Choice word field guides, a key component of this approach, become a routine and rhythmic classroom activity. They establish a foundation for language study by teaching students how to investigate words and interpret their findings. Building upon this foundation, language field guides prove to be remarkably versatile in various classroom settings.

Guiding Students to Uncover Meaning in Language

Whether teaching advanced 12th-grade IB classes or diverse 7th-grade groups, a common observation is that students often lack practice in dissecting language at the word level to construct and interpret meaning. While students understand that writers intentionally choose words, the focus often remains on broader concepts like themes, character development, and thesis statements. Consequently, the crucial skill of analyzing the subtle yet impactful word choices that contribute to the overall effect of a text is often overlooked.

This is where the power of language field guides truly emerges. After students become comfortable with free choice field guide entries, the next step is to direct their attention to significant words – the most impactful language choices within both literary texts and their own writing.

Exploring the Most Significant Words: A Guided Approach

Reading serves as the starting point, as our reading habits deeply influence our writing.

Using a Text Studied in Class

- Selection: Choose a specific passage from a longer text being studied in class, or a complete article.

- Identification: Challenge students to identify the most important word or words (you determine the number) within the selected text.

- Exploration: Encourage students to explore their chosen words, emphasizing discovery. What new insights can they gain about the word? How does it reshape their understanding?

- Synthesis: After individual exploration, guide students to synthesize their chosen words using a concept circle. How do these words collectively illuminate a concept within the text? Do they alter, enhance, or develop a particular idea? In essence, how do these words connect, and what novel understanding do they create when considered together?

Example in Practice:

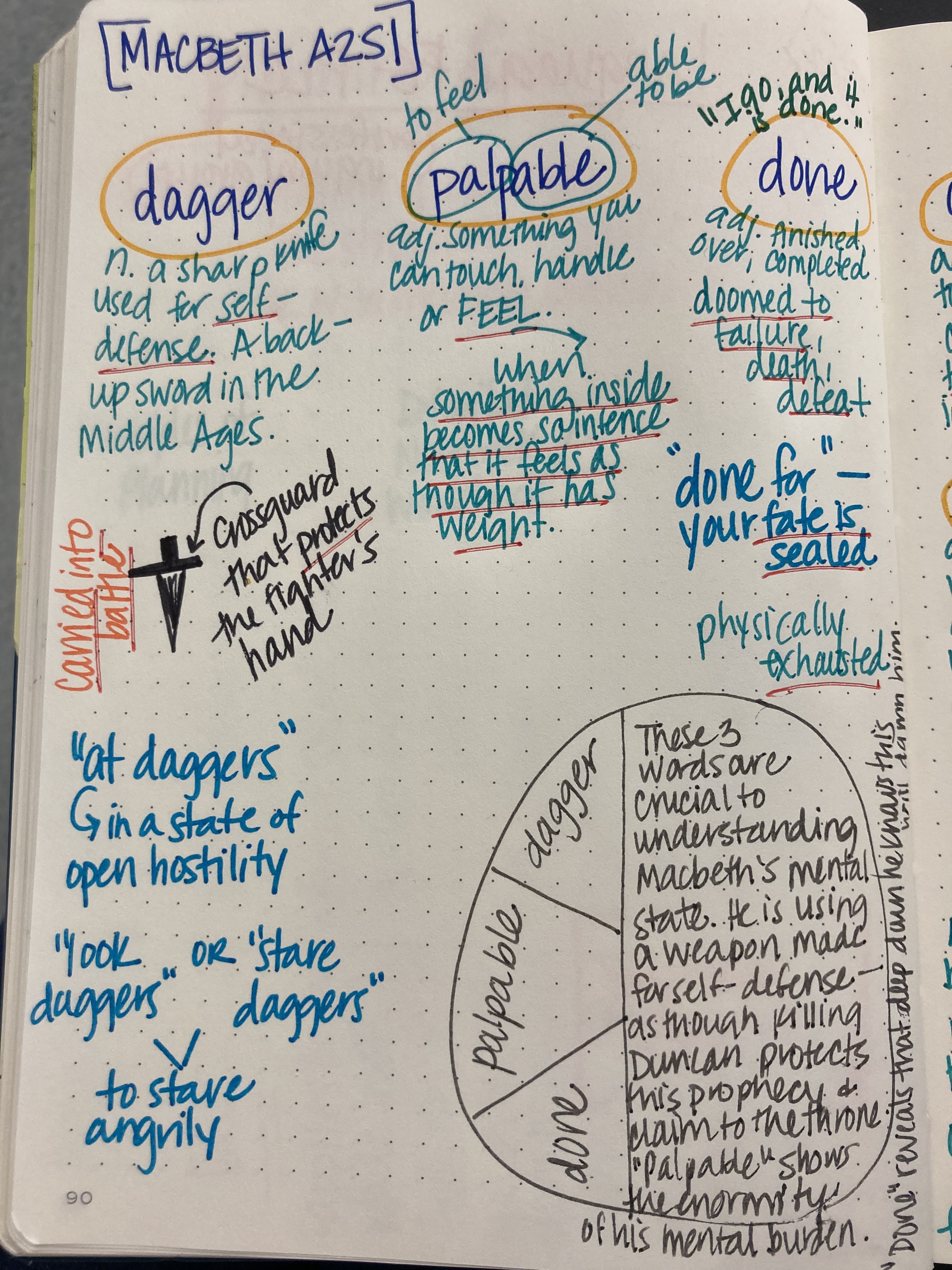

Alt text: Student language field guide entry for Macbeth soliloquy, highlighting ‘dagger’, ‘palpable’, and ‘done’, showing definitions, contextual phrases, and a concept circle connecting the words to Macbeth’s motivations.

When studying Macbeth, I aimed to guide my students towards a close reading of Macbeth’s dagger soliloquy, prompting them to consider whether Macbeth is inherently evil or undergoing a mental health crisis.

I instructed students to select three words they perceived as most crucial and significant in this speech – words that the soliloquy essentially pivots upon. Mirroring the choice word field guides, I prioritized student agency, allowing them to determine what they deemed important and worthy of in-depth study. In this instance, Isabelle selected “dagger,” “palpable,” and “done.”

Similar to a choice word field guide, she meticulously recorded parts of speech, definitions in her own words, relevant phrases and textual excerpts containing the word, and illustrative sketches to deepen her comprehension.

It’s evident that Isabelle isn’t simply copying dictionary definitions. Instead, she’s documenting aspects that resonate with her, underlining (in red) significant realizations. The objective isn’t merely to define “dagger,” but to explore what Shakespeare’s specific choice of “dagger” reveals about Macbeth’s character and motivations.

Subsequently, she synthesized her findings within a concept circle. The revelation that a dagger is a secondary battlefield weapon primarily used for self-defense led her to infer that Macbeth might be attempting to protect something by murdering Duncan – perhaps safeguarding the prophecy or his ambition to become king. By framing the murder as self-defense, Macbeth could more easily rationalize his actions, which is a central struggle within his soliloquy. She discovered that “palpable” can possess a figurative, emotional weight, signifying an overwhelming feeling, aligning with Macbeth’s apparent emotional turmoil in this scene. Intriguingly, she noted that “done” can also imply “doomed.” Thus, when Macbeth declares “I go, and it is done,” he alludes not only to the murder but also to the potential damnation of his soul.

Applying the Guided Approach to Student Writing

Analyzing one’s own writing critically becomes more accessible after practicing on external texts. If students can effectively explore and reflect on significant words in Macbeth (or their independent reading, mentor texts, or excerpts from works like The Great Gatsby), they can replicate this analytical process in their own writing.

- Direction: Instruct students to focus on a piece of their own writing. (This could be a work in progress, a near-final draft, or a previously completed piece.)

- Identification: Ask them to reread their work and identify their own three most crucial, significant words – the words upon which their piece hinges.

- Exploration: Encourage students to explore these words, emphasizing new discoveries and connections among them.

- Synthesis: Guide students to integrate the three words in a concept circle. How do these words relate to each other? What do their explorations reveal about the ideas presented in their piece? Do these discoveries inspire the writer to incorporate new ideas? Do these words accurately reflect the writer’s intended message? Are adjustments needed to emphasize a different word’s significance?

Another Example:

Alt text: Student language field guide entry analyzing student’s own writing, focusing on ‘vulnerable’, ‘safe’, and ‘complicated’ in song analysis, revealing deeper understanding of interconnectedness.

Isabelle applied this method to her nearly completed free-choice analysis essay, focusing on Louis Tomlinson’s song “Defenseless.” Through this word exploration, she gained crucial insights for her essay:

- The three selected words effectively encapsulated the core ideas she aimed to convey about the song.

- “Complicated” was a concept she struggled to articulate during drafting, yet it proved remarkably fitting upon deeper examination.

- Discovering “complicated’s” connection to interconnectedness allowed her to articulate a more nuanced understanding of the song: it doesn’t simply juxtapose vulnerability and safety; it demonstrates a deeper interconnectedness. Tomlinson’s vulnerability fosters a sense of safety in the listener, highlighting a reciprocal relationship.

This process can lead to several outcomes:

-

Struggle to Identify Significant Words: A student might struggle to pinpoint three significant words or select words that lack true significance. This is acceptable and informative. It highlights areas for growth and encourages more intentional word choice. In such cases, guide students to consider: “What words are missing that should be central? Which words best represent the core message I’m trying to communicate?”

-

Successful Exploration, No New Epiphanies: A student may effectively explore three important words but not arrive at groundbreaking new insights about their piece. This is also valuable. The very act of questioning “What are the most significant words in my piece? Which words form its backbone?” strengthens intentionality in writing. Students benefit from the practice of word exploration and connection-building, regardless of immediate major revelations.

The Value of Guided Word Exploration

-

Enhances Critical Reading Skills: “Most Important Word” entries cultivate close, attentive reading. Students dissect texts at the word level and forge connections between words and overarching ideas. This is the kind of analytical reading we aim to foster independently in students. Field guide entries provide a structured framework for this type of thinking.

-

Focus on Discovery: The central question guiding field guide work is: “What did you discover about this word?” Moving students beyond simply copying dictionary definitions requires consistent effort and reinforcement. Often, the words students initially deem “most important” are common. This method nudges them to delve deeper, uncover novel insights, and establish new connections.

-

Illuminates Student Writing: When students analyze both published texts and their own writing through this lens, the link between reading and writing strengthens. They recognize that they, as writers, make word choices akin to professional authors, and that these choices carry substantial weight and meaning.

This approach provides dedicated time and space for students to examine their writing at a micro-level. Traditional writing instruction often prioritizes macro-level concerns – overarching ideas and structure. Amidst the demands of extensive essay writing, methodical consideration of individual word choices can be challenging. This method provides that opportunity and can even spark new ideas to enrich their writing.

Language field guides are a unique tool that seamlessly integrates into both reading and writing workshops, offering a versatile approach to language learning.

Alt text: Text graphic with the title “Language Field Guides” and a subtitle emphasizing exploration and discovery in language learning.