For my family, Thursday wasn’t just closer to Friday; it was TV Guide day. Like clockwork, the magazine would arrive, substantial in hand, promising a week’s worth of televised entertainment. In our living room, a space was consecrated next to my father’s armchair, a designated spot for TV Guide when not in use. This simple rule was a rare, undisputed law in our household. Losing the TV Guide was akin to a minor domestic crisis, triggering a search as urgent as when our dog decided to explore the neighborhood solo. For a New York family navigating the channels, the TV Guide was indispensable.

Growing up in the eighties, television was a constant companion. Living just north of New York City, we were in a prime location for broadcast TV. Cable was a luxury we didn’t have until later in high school. This pre-digital TV landscape fascinated me. I became an expert in the intricacies of broadcast channels, much like a commuter obsessed with subway line updates. Call letters, channel numbers, network affiliations – these were my trivia. I could identify network groups by their program listings clustered together in the TV Guide. For New Yorkers, this knowledge was especially relevant, navigating the crowded airwaves of the city and surrounding areas.

It was a stop-the-presses moment whenever the TV Guide went missing, on the same level as having to scour the neighborhood whenever the dog wandered off.

Today, channel numbers are almost relics, except perhaps on news vans. But back then, armed with a dial, I could navigate the static-filled spectrum, reaching even the distant UHF channels like Channel 83, stopping precisely where I intended. In the New York metropolitan area, we had access to the core network stations and a handful of independent channels. With our trusty rotating antenna, we could even pull in signals from stations in Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania – depending on the weather, of course. The dense geography of the Northeast meant our TV Guide was a treasure trove of viewing options. More captivating than any young adult novel, it was my weekly must-read, a window into the world of New York television.

Why People Don’t Like “I Love Dick” (Hint: Because It’s About Women)

The TV Guide served as the blueprint for our weekly television consumption. Its opening pages were packed with articles, reviews, and interviews, all hinting at upcoming episodes. A new MacGyver episode clashing with a “very special” The Hogan Family? Decisions had to be made. Reading the concise episode summaries (“MacGyver infiltrates a smuggling ring to retrieve stolen artwork”) helped strategize viewing schedules – crucial when a single TV served the entire household. For New York families, planning TV time with the New York Television Guide was a ritual.

If a new episode of MacGyver ran up against a Very Special Episode of The Hogan Family, you knew you would have to make a decision.

This concept feels archaic now. TiVo, on-demand services, and internet TV have made scheduled viewing obsolete, replaced by the freedom of binge-watching on laptops in bed. Even the TV Guide logo mirrored the evolution of television screens – rounded in the early days, squared in the 70s, and finally stretched horizontally for the flat-screen era.

But in its prime, TV Guide was more than just a listing; it fostered a shared cultural dialogue around television, even for shows you didn’t watch, much like reading The New York Times Book Review for books you might never pick up. Before the internet became the town square for such discussions, TV Guide brought it to the masses, a far cry from today’s flimsy, celebrity-gossip magazines at the checkout. Its editors championed television as a serious art form. To that end, they recruited literary giants to write for its pages. John Cheever, a Pulitzer Prize winner, explored the world of TV commercials:

I am not an aesthetician, but in my opinion any art form or means of communication enjoys a continuous process of growth and change, rather like something organic, and one must be responsible to one’s beginnings.

Alongside Cheever, the magazine featured critical essays and social commentary from Clive James, Anthony Burgess, Margaret Mead, John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates, David Halberstam, and William F. Buckley, Jr. (“The Winter Olympics aren’t a velleity for the Swiss,” Buckley wrote in 1988. “They are a compulsion.”). For decades, TV Guide, much like The New York Review of Books, treated television as culturally significant and assumed its readers felt the same. It spoke to an audience comfortable with both tuning in and reading books. For New Yorkers, a sophisticated and media-savvy audience, this approach resonated deeply.

TV Guide was more than a guide; itallowed you to participate in the cultural conversation of television even through those shows you never watched, like you might read The New York Times Book Review about books you don’t ever plan to read.

And so, theory entered the living room. The August 8, 1970 cover asked, “Why the Feminists Condemn Television?” featuring Marlo Thomas of That Girl.

It tackled social issues: “How TV Police Shows Give Police a Headache” (December 18, 1971, with the Partridge Family on the cover).

It even engaged in media criticism: the September 21, 1985 issue with Michael J. Fox teased a retrospective on the Iran hostage crisis, questioning fairness and TV’s influence. For New Yorkers, always at the center of media and social discourse, these topics were particularly relevant.

This was the platform where anthropologist Margaret Mead, in 1973, profiled An American Family, PBS’s early reality TV series. Observing the Loud family, Mead recognized “a new kind of art form … as significant as the invention of drama or the novel — a new way in which people can learn to look at life, by seeing the real life of others interpreted by the camera.”

Within this mainstream medium, Joyce Carol Oates, in 1985, passionately defended Hill Street Blues, praising its “Dickensian” character studies and audacity, exceeding typical television expectations.

In was in this cozy medium that Joyce Carol Oates, in 1985, wrote a simmering defense of Hill Street Blues, a show that shocked her for presenting something beyond what she expected of television.

Oates’ essay followed Susan Sontag’s defense of “camp” and preceded analyses of shows like Mad Men by critics like The New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum, who saw them as vehicles for complex moral narratives, once the domain of novels. Nussbaum’s Pulitzer Prize in 2016 for Criticism acknowledged this evolving art form at the intersection of commerce and creativity. In response to the Mad Men finale in 2015, she noted a craving for “that rude resistance to being sold to, the insistence that there is, after all, such a thing as selling out.” For discerning New York viewers, these critical perspectives added depth to their TV experience.

Television’s once rigid boundaries have dissolved. Gone are the neat genre classifications in TV Guide listings, the screen aspect ratios, and the limited episode structures. Shows are binge-watched, re-watched, and arcs are crafted with an understanding of human memory’s imperfections. Arrested Development’s visual gags in Season One can set up plot points in Season Two that only become apparent on a re-watch. Television has transformed from passive viewing to an immersive, subscription-based experience. For New Yorkers, accustomed to fast-paced media consumption, this shift was readily embraced.

TV Guide’s writers cared about viewer reception in a world of limited networks. It was an era where literary and visual cultures intertwined. Dick Cavett mediated disputes between Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer, while Sontag and Marshall McLuhan appeared in Woody Allen films. TV Guide recognized television as a lens for understanding history and critiquing current events. Its highbrow pursuits extended beyond writing. For the March 5, 1966 cover, Andy Warhol created a Beatles-esque silkscreen of Get Smart’s Barbara Feldon. Salvador Dalí painted a moonscape for the June 8, 1968 issue, alongside an interview with the artist. This cultural infusion reached homemakers, teenagers, and anyone wanting to know Johnny Carson’s guests or Sunday’s Creature Feature lineup. For New York’s diverse population, TV Guide offered something for everyone.

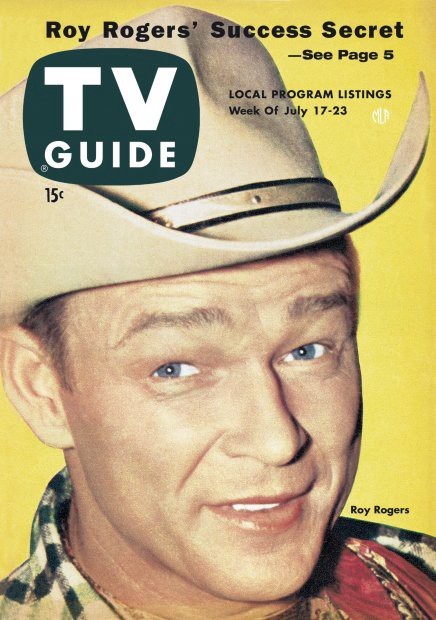

Walter Annenberg, from a publishing lineage, launched TV Guide in 1952. His father published the Daily Racing Form and later acquired The Philadelphia Inquirer. Annenberg consolidated existing local TV listings publications from major cities like New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, creating a national resource with regional variations. The first national issue, featuring Desi Arnaz, Jr. on the cover, appeared on April 3, 1953. The headline – “Lucy’s $50,000,000 Baby” – hinted at the magazine’s early critique of celebrity culture. For New York, a media capital, this nationalization and celebrity focus marked a significant shift in television media.

Curating a New Literary Canon

TV Guide became the definitive guide to television. Its ubiquity was such that furniture manufacturers designed chair pockets specifically to hold it. In the 1980s, a TV Guide board game featured trivia questions in digest-sized booklets mirroring the magazine.

In 1988, Triangle Publications sold TV Guide to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. for $3 billion. Under Murdoch, it became a thinner, more pop-culture oriented publication, diminishing its critical commentary, except for the “Cheers & Jeers” section. A decade later, it was acquired by GemStar International Group, known for VCR Plus, shifting focus to digital menus and Entertainment Tonight-style programming on the TV Guide Channel. For New York, witnessing this evolution of a media institution was part of the city’s ongoing media narrative.

TV Guide’s golden age was destined to end with the rise of DVRs and digital guides. The magazine shifted to a larger format in 2005, eliminated local editions, and became bi-weekly. It still exists at checkout counters, alongside celebrity magazines, reportedly still profitable.

TV Guide,in its best incarnation,was doomed long before the developments of DVRs.

My own television habits have changed drastically. I record Jeopardy! nightly. When I binge-watch, it’s often older shows like The Rockford Files or thirtysomething, tapping into nostalgia for older production styles, analog-era storytelling, or even just cars with metal bumpers.

This nostalgia is partly snobbery, but also a reluctance to commit to new shows that demand more attention. Even excellent series like Sherlock, with its movie-length episodes and intricate plots, can feel like a demanding project.

Television once brought external forces into our living rooms. Now, it has expanded beyond the living room, following viewers everywhere. Perhaps TV Guide’s original model is obsolete because we are now more informed about our viewing habits than any critic could tell us. For New Yorkers, always at the forefront of media trends, this self-directed media consumption is the new normal, a far cry from the New York Television Guide era that once shaped our viewing habits.

[